Americanism Redux

September 14, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1773

The world I know and love is falling apart.

Falling apart.

What can I do? What can I do to help? Is there something, a talent I possess or an opportunity given to me, that can make a difference?

Now is the time. Right now, not next year, not next whenever when the stars have aligned, but…now. I have to do what I can do! I have to try….

Because the world is falling apart.

(falling apart)

* * * * * * *

Pick up the British newspaper called The Public Advertiser today, 250 years ago, and you’ll read a pair of articles. Two strange titles: first, “Rules By Which A Great Empire May Be Reduced To A Small One”, and second, “Edict By The King Of Prussia.” The articles are satire and sarcasm of the most biting, piercing, and cutting style. Total smart-ass.

They make the point, though. Within the satire is the argument that British imperial policy and policymakers are pushing the British colonies to the breaking point. The writer pleads—as much as a smart-ass can plead—for a change in mindset and decisions that will reduce the tensions, address the grievances, and reset the balance to harmony. Make it right before it goes permanently bad. The writer approaches the point from a variety of angles, from informed citizen, from person in power, from victim of mistakes and misdeeds.

The London-based author, the smart-ass, is Benjamin Franklin. He’s doing what he thinks he can do to help a situation that, left untended, will sink into demonic levels of chaos. He’s trying to prepare the British people and the British public for the fall session of Parliament when imperial policy will be hotly debated. The next few weeks are crucial and this is what he thinks he can do. If I move them, they can move the politicians.

(smart ass)

Today, a reader of these articles, Catharine Macaulay, is in London, England. She’s absorbing every paragraph, every sentence, every word. She’s in total despair. Catharine is a fervent supporter of the colonial rights movement and a staunch anti-imperialist. Just a short while ago she wrote to John Adams: “I hope to hear that the appearance of a renovation of the union betwixt the Colonies has become a reality. It is the Jealousies and Divisions that has always subsisted among you that has encouraged (British imperial) Ministers to attempt those innovations which if submitted to naturally will lead to the subversion of your Liberties.” Macaulay places her hopes on the strength of colonial cohesion and unity to resist and remove destructive imperial policies. Hers is a different approach from Franklin’s.

(Catharine Macaulay)

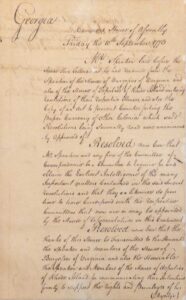

In Macaulay-esque fashion, the legislative assembly of the colony of Georgia—named after King George II—voted a few days ago to organize their “committee of correspondence” (CofC). The Georgia CofC is the latest response to the call from the Massachusetts legislative assembly ten months ago to form these entities in advancing colonial rights. The CofC in Georgia will maintain communication with other CofCs in other colonies, by letter via boat or horseback. They will seek to coordinate responses to imperial policies and disseminate information on colonial rights to local people in the colony. It’s a long way from Savannah, Georgia to Boston, Massachusetts. What will bind them together to achieve Macaulay’s hopes of a solid union?

(Georgia’s announcement)

Communication is the top priority of Adam Stephen in Winchester, Virginia today, 250 years ago. He served as an officer under the command of Colonel George Washington during the French and Indian War of 1754-1763. He and other veterans from that conflict are angling for new land as a reward for their service. Stephen struggles today with the massive challenge of sending letters to his fellow veterans. He wants to inform them of an upcoming meeting next month in Winchester where they can get more information about the land available—or owed, as they see it—to them.

Stephen’s best bet is to urge Washington to use his extensive personal network to spread the news of October’s Winchester meeting. Stephen is in that unique position of his attempt to communicate while also relying on someone else to communicate on his behalf. From his view, the whole thing will hinge on Washington. In this sense—in the reality of communicating to others and needing others communicate for him—he’s not far from Franklin’s pair of articles in London’s Public Advertiser.

Think of it. A group of Virginian military veterans who fought on behalf of Great Britain, George III, and the British Empire. To the west, the allure of a reward awaits them. At Winchester, the first step will be taken. He hopes.

For King and Country and us, the former band of merry men.

(Adam Stephen)

Also

Today 250 years ago, having crossed the St. Lawrence River near Quebec, Canada, Hugh Finlay begins a journey toward the community of Falmouth on the Atlantic Coast in the colony of Massachusetts (now Maine). He’ll be meeting four Native guides who will help him find, and then mark, a path for a postal road connecting Falmouth and Quebec. Only days from now Finlay and his ten-man expedition will be in a world of mosquitoes, black flies, hornets, wasps, and ticks, the world of pine and spruce and fir and aspen.

Finlay’s outlook is brooding in that he’s excited about the task but sullen about the British colonies, especially the man who was the first originator of the colonial postal service, Benjamin Franklin. Finlay dislikes Franklin and sees him as a prime stoker of anti-imperial resentments. He’s here on the St. Lawrence eager to take over control of Franklin’s postal system, a targeted slap in the face of the man who, it’s been whispered, stole the controversial letters written by Thomas Hutchinson and Andrew Oliver.

Let’s leave the comfort of the St. Lawrence River and plunge into the woods, our group of road-markers on a trip of discovery. Forget the old Franklin. It’s my expedition now.

(a result of Finlay’s expedition)

For You Now

Stopping the slide. In this entry we’re seeing exertions to stop the slide from not good to bad, from bad to worse, from worse to explosion.

A particular type and form of argument, of persuasion, of rhetoric, in the name of change. Franklin.

An assumption about that state of togetherness and solidarity, and a further assumption as to the costs of not having either one. Macaulay.

An added entity to a new group-method of collecting and distributing information. Georgia’s CofC.

A focus on next things from past efforts, a benefit of services rendered toward opportunity presented. Stephen.

And taking up a challenge to discover and expand upon an innovation someone else started. Finlay.

To make things better, to stop the slide and turn things around, you are open to your own actions or to those of someone else. You’ll read about it, hear about it, see about it. You will say “yes” to whatever that thing is because of…what? Something will make you say “yes” to stopping the slide at some point. Maybe you clearly anticipate the effectiveness of it, maybe you see just enough of it, or maybe it’s the best of a bunch of unappealing alternatives. Maybe you’re desperate. Something will make you say “yes” at that time. And then you’ll hope that the slide truly stops.

(saying yes)

Suggestion

Take a moment and consider: what will make me say “yes” to an approach that stops the national slide I see?

(time flows like the water in a river–forward)