Americanism Redux

October 19, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1773

It comes all jumbled up and twisted together. Knotted and clutched up, in a ball. You have to do the untying and unraveling. Hold a string in one hand, a different string in the other hand, a third string between your teeth and, looking down, you still see about three hundred other strings all wound into a bewildering tangle.

How in the world can any sense be made of it? How to cope when what you want is a single thread in a world of knots and tangles.

* * * * * * *

The western horizon of the Atlantic Ocean is the same today, October 19, as it was yesterday or last week. Gray clouds, hanging low. The ocean waves and heaves. Plowing the waters, a salty spray dampens the foredeck of the Dartmouth and the ship’s captain, James Hall. Hall hears the thick ropes and tarred planking creak on his ship. White canvas stretches and claps with the strong wind. The ship’s crew draw their coats a little tighter and pull down their hats a little lower in an effort to keep warm. The routines of hierarchy and command mark yet another day aboard the floating world of the Dartmouth. Clarity in the consistency.

Below deck, where whale oil and spermaceti were stored in barrels as recently as weeks ago, more than a hundred chests of East India Company tea are packed away. Inside the chests are brick-shaped forms of the dried substance. Black dynamite. Not far from the tea chests sits a crate. The crate holds books. Within each book are pages printed with the poems and essays of Phillis Wheatley, newly written and published by the newly unenslaved. Golden key.

The stuff of liberty and freedom and the stuff of constriction and constraint, all tied up together on the same ship. Black dynamite and golden key.

(a ship’s hold carries the future)

* * * * * * *

Phillis Wheatley is staking her life on these books carried in Dartmouth’s hold. A week ago she received her freedom from the husband and wife who enslaved her. Phillis has shown to them a joyous gift for reading and understanding classical literature and poetry. She’s written some of her own poems patterned after the classical style. Several of the poems are collected together in this book, the copies of which are in the crate, the key that unlocked her chains. She wants to sell as many of the books as she can to start her life and livelihood as a free black woman. Yesterday, she wrote to wealthy David Wooster of New Haven, Connecticut. Wooster doesn’t know her, although he is interested in abolishing enslavement and has a neighbor who introduced him to Phillis’s achievements. Phillis won’t know anything about Wooster’s willingness until he can read her poetry. And that won’t happen until the Dartmouth docks in Boston with the crate of her books…and the cargo of tea.

Tied together.

(David Wooster, a few years later)

* * * * * * *

The word “Dartmouth” is on another person’s mind, too. It’s not the name of a ship in this case but rather the name of a man, the Earl of Dartmouth, current Secretary of the American Department under the Parliamentary government of Lord North, reign of King George III. North Carolina Royal Governor Josiah Martin, appointed by imperial officials, believes that Dartmouth is his best chance at getting more power, more money, more status. He wants Dartmouth to select him to be the “Superintendent of Proprietary Affairs” in the British colonies while retaining his North Carolina governorship. Martin knows the appointed position would give him broad authority to make and enforce policy on land ownership, trade regulation, political offices, and paper currency. It would be an office of sweeping scope and power, and all of it would be decided and arranged by a handful of well-connected people. Josiah Martin knows how power works—and doesn’t work—flows—and doesn’t flow—in the sprawling world of imperial Britain.

He reaches for the strings.

(NC’s Royal Governor, Josiah Martin)

* * * * * * *

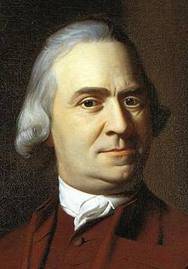

Samuel Adams is thinking about the same Dartmouth. Adams realizes that most British colonists regard Dartmouth as a friend and ally within the imperial government, their advocate in the halls of power. They see him as a good man. But to Adams, “Men in such elevated Stations should be great as well as good.” Adams fears that the more deceitful members of the British government will exploit the British colonists’ excessive hopefulness in leaders like Dartmouth. Adams suspects that two things are coming: first, an election of new Parliamentary members who will know how to flatter and trick Americans; and second, a British-led war with another European nation that will distract Americans from their pursuit of rights and liberties. “The Safety of the Americans in my humble opinion,” writes Adams, “depends upon their pursuing their wise Plan of Union in Principle & Conduct.”

Untie to retie.

(Samuel Adams)

* * * * * * *

But are there signs of such a “Plan of Union”? Well, it depends on where you look and what you’re looking for.

Legislators in the British colony of Maryland adopted two days ago a resolution that hints ever so slightly of Adams’s desired “Plan of Union.” Forty-eight hours before Adams crystallized his thoughts, the Maryland Assembly acted on suggestions by legislatures in Massachusetts, Virginia, Rhode Island, and Connecticut to establish a group to conduct “a mutual Correspondence and Intercourse with our Sister Colonies.” Eleven members of the legislature will now serve as Maryland’s Committee of Correspondence. Of course, it’s a long way between the collection and dissemination of information (the CofC’s task) and a plan of coastal-continental union. A long, long way. Long enough to make the Atlantic Ocean seem like a mill pond.

Stretch a string too far and it breaks, leaving the rest in a knot so tight as to be useless.

(The Maryland Inn in Annapolis, where some of the legislators stayed or met)

* * * * * * *

A remarkable event has just ended in Philadelphia, precisely the kind of thing a Committee of Correspondence would want to share with other such groups.

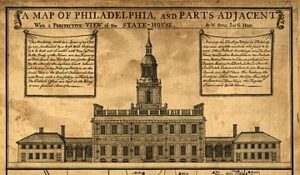

Held at the elegant Pennsylvania State House (later known as Independence Hall), more than three dozen leaders of eastern Pennsylvania’s pro-colonial rights movement met forty-eight hours ago and grappled with the issue of the tea shipments. They haggled and debated about what to do and say as a unified group. Their topic: the tea currently below-decks on the eight vessels in the North Atlantic Ocean.

They settled on eight resolutions. The resolutions stood on four points—one, that freedom means the right to one’s property and what to do with it; two, that the tea tax is a symbol of seizing property without consent; three, that opposition to this policy must be steady, pervasive, and virtuous; and four, that the person who rejects such opposition and supports the tea tax is an enemy to the country.

It’s now two days on and the halls of Pennsylvania State House are silent again. The ideas, words, and emotions of the meeting are forever gone. What’s left are “The Philadelphia Resolutions” and the group that produced them are ready for their publication in next week’s Pennsylvania Gazette, owned by Benjamin Franklin.

A new set of strings from fibers never to be known.

(a view of the Pennsylvania State House in 1752, known to us as Independence Hall)

* * * * * * *

It’s getting dark as the sun sets below the tree tops. Crickets will start to chirp and the blue jays will call out a final time or two before settling in to sleep on the pine branches. Before long, the big cats and the big dogs will start up—the panthers screaming, the wolves howling. Black bears will begin their nightly prowl and forage. The fading sunlight show deep reds and golds on the leaves of the hardwood trees. Soon, they’ll form into a black mass between you and the brilliant stars.

The nights come early this time of year on the Three-Notch Road. It crosses from the Virginia coast into the Valley of Virginia. For now, today, here on the Three Notch Road in the middle of Goochland County, no one can be seen, no family in a wagon, no solitary horseback rider, none going west into the Blue Ridge and beyond, to Kentucke. But likely tomorrow, or the next day, or the next week, someone will come along seeking a new life where old lives have long lived. They’ll add to the clash in the west and, increasingly, to the carnage in killings of one’s or two’s or three’s.

From the North Atlantic Ocean to the Three-Notch Road.

Where life is all knotted up and the strings hard to disentangle.

(a modern portion of Three Notch Road)

Also

29-year old John Cabot belongs to First Church in Beverly, colony of Massachusetts. Last Sunday he heard the church’s young minister give a sermon. Cabot is from a family of eleven children and wants to follow the example of his father and enter the mercantile business with heavy reliance on shipping. In any normal week he’s got about a thousand strings and threads on his mind but these don’t seem to be entirely normal weeks nowadays, do they? So, a person can’t help thinking about that sermon.

Like Cabot, the Reverend Joseph Willard is a Harvard graduate. He’s been on Harvard’s faculty until just last year when he took on the challenge of being First Church’s minister. With public controversies in colonial Massachusetts rising like flames around him, Willard had chosen the text for last Sunday’s sermon carefully. The Bible’s Book of Hebrews, Chapter 2, Verse 3. “how shall we speak if we neglect so great a salvation.”

“When we look around us and take a view of the world we see moral evils greatly prevalent,” said Willard from the pulpit.

Then later…

“Can anything be more terrible than to have God for an enemy, Who can deprive us of all happiness and make us exquisitely miserable?”

Willard wrapped a chord of admonitions around these statements: remember the source of your faith, the source of your hope, the true sovereign of your life.

And then he bid them good week, saying, “God grant that you may be enabled to take this wise course, for the sake of his Son and Redeemer.”

Willard offered his way of untying. Cabot has to decide how far to go.

Strings and threads.

(First Church, Beverly, Massachusetts)

For You Now

We’ve found something of great importance in today’s Redux. We’re seeing two types of cargo on the Dartmouth, each with the power to change life as it’s known in the British colonies. One is a substance that is already enflaming public opinion. The other is an art that holds the hope of freedom over enslavement. We’re also seeing a meeting in Independence Hall where people, animated by ideas, craft a deeply meaningful written statement, one well ahead of 1776’s Declaration and 1787’s Constitution. The cargo/document trio opens a universe with implications for a multiverse. And not a drum beaten, not a flag flown, not a song sung, not a moment yet commemorated in verse and stone. Still, in the third week of October 1773, it’s all right here in front of us in the form of basic principles and fundamental ideas. More than that, incredibly, everywhere we’re turning we see possibilities and potentials, any of which can touch and spark, collide and explode.

That’s why I referred to strings and threads twisted into a packed shape. They’re connected and wound up. Trying to undo them is a maddening venture. The temptation to clutch, pull, and yank usually makes things worse, the ball knotting to the point of glued, more indecipherable and impervious to understanding.

As hard as it is to do, and it’s nearly impossible when time and events press against you, the only way to make progress from the tangle is to be patient, use a delicate grip and keep a steady hand. Relax, loosen, unwind, lay aside. Repeat. If not, you’ll succumb to going faster when faster takes you to ruin. You’ll get there quicker because all you’ll be carrying are bias and insistence. And the threads will turn to shackles.

(The Mary, Undoer of Knots)

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: how many threads do you see in your hand now, in 2023?

(The River as threads)