Americanism Redux

November 30, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1773

It’s here. No more wondering. The thing is here, right in our laps. And now things happen with blinding speed.

* * * * * * *

(Dartmouth)

The British ship with the East India Company tea is now in Boston harbor. And things have started to happen.

Today, 250 years ago, John asks his wife to help convince her parents. She fails. It’s John’s turn now and he uses every argument with them—his in-laws—that he can think of. Begs and pleads. They’re not budging. They won’t leave the safety of Castle William in the middle of Boston harbor. John can’t blame them. They can recall all too well the ordeal of a few weeks ago when a group turned a crowd turned a mob—and attacked John’s in-laws’ home, threatened their lives, terrorized them for hours because Richard Clarke, John’s father-in-law, refused to give up his position as East India Company tea consignee, an EIC tea distributor. Since then, the Clarkes had fled to Castle William and they won’t come out no matter what John says in the next minutes. Exasperated, John leaves them at the Castle and returns to downtown Boston, to Old South Meeting House, today, 250 years ago.

He enters the Old South through a packed crowd that is loud in sound, electric in energy, strong in purpose. One count has the number of people at 5000, stuffed inside Old South, Boston’s largest indoor meeting space, as well as ringing several rows deep outside the place. John pushes his way to the front where the main speakers and the meeting’s facilitators stand. Samuel Adams is there along with John Hancock. With them are John Rowe, Jonathan Williams, and William Phillips. The crowd is forceful but not wild, united but not mindless.

This is the second massive meeting in as many days. Yesterday’s meeting had started out at Faneuil Hall but the crowd grew and grew in number until the mass had to be moved to Old South. The group called itself “The People” and they produced a consensus on the 29th with a statement called, tellingly and with subsurface religious meaning, “The Body of the People”. Their agreement was that the East India Company tea would never be accepted and never be off-loaded onto the docks. “The People” had stamped their canes, shouted their voices, and pounded their fists in approval. That night of the 29th, twenty-five men led by Captain Edward Proctor had volunteered from the Sons of Liberty to guard the tea aboard ship in Boston Harbor. Among the men who immediately enlisted in the guard were Henry Bass, Moses Grant, Thomas Chase, and Dr. Elisha Story.

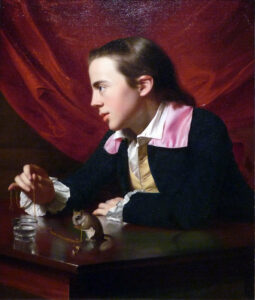

But today, on November 30th and again at Old South, John Singleton Copley begins to state the case of his father-in-law who was one of the designated EIC tea distributors, or consignees. Already known as a talented painter—he’d painted a portrait of Samuel Adams—Copley calls for the crowd to hear his compromise: let the tea be landed, place it in a storehouse, and have it guarded by Proctor’s volunteers, and then things can be sorted out. Surely this is a reasonable course of action.

(John Singleton Copley)

Copley barely finishes his statement before the crowd thunders back with booing and hissing.

Only minutes pass before a formal messenger arrives with another statement to be read before the crowd. Massachusetts Royal Governor Thomas Hutchinson has met with the upper council of the colonial legislature and produced an order for the crowd at Old South to disperse or face dire yet unspecified consequences. Hutchinson’s order is read aloud. “The People” roar back with one voice: they repeat their vote to refuse to let the tea be unloaded from the ship in the harbor.

The meeting concludes. The five-man unit of Adams, Hancock, Rowe, Williams, and Phillips begins planning to travel to New York City and then to Philadelphia, two other sites where tea shipments would arrive. The goal is to carry written records of the past two days of proceedings in Boston. They want to meet with local anti-tea leaders in the two port communities

And the ship stays in the harbor, tea on board, nothing unloaded, the volunteer guard standing and watching it from Griffin’s Wharf.

(Old South Meeting House)

Day by day and hour by hour, the thing rushes ahead. Actions and reactions, moves and counter-moves, forward and backward and side-to-side.

* * * * * * *

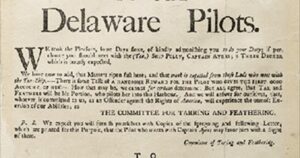

The mood in Philadelphia is hard to predict. That’s because three days ago on the 27th, a group calling itself “The Committee For Tarring and Feathering” had declared in humorous fashion the consequences for any of the river pilots who might guide the tea ship into port. Then again, who could exactly tell where the joke ended and the reality began? The line between them is muddied by a clearly serious and unsmiling part of the Committee’s declaration: first, freedom is the birthright of Pennsylvanians as Americans; second, no one on earth has the power or right to tax them without their consent; and third, the tea laws embodied a form of taxation that was seeking to do just that without anyone’s consent in Pennsylvania or the rest of America. The Committee closed with a splash of fun: all pilots helping EIC consignees should take flight and fly without feathers at the earliest moment.

(The Committee’s statement)

* * * * * * *

The white paint of the Shirley Meeting House sparkled in the daylight this week. On November 25th, open for its first service, the church congregation celebrated a formal Day of Thanksgiving. The town and the church reflect the community’s deepest respect for a former colonial governor of Massachusetts, William Shirley. He was active, energetic, and a visionary. Local people knew him and liked him and regretted the end of his service as governor in 1756, after eleven years in office. When he died two years ago in 1771, it felt a natural act to name the town in his honor. Yes, those were the days; imagine it—voters and residents in a Massachusetts community thinking so highly of their governor that they name a town after him. There’s a greater chance of naming a town after Satan’s Hell than there is after current Governor Thomas Hutchinson.

How times have changed as November ends in 1773.

(Shirley Church)

* * * * * * *

Jonathan and Ruth Slocum are back home, in a way, in Warwick, colony of Rhode Island today, 250 years ago. They’d attempted to live in the wooded regions of central Pennsylvania but found it too difficult to be that far away from more established towns. They’re Quaker in their religious faith, however, and the latest turmoil between the pro-tea imperial government and anti-tea segments of colonial society is verging on chaos and violence. The Slocums think constantly about revisiting their decision to abandon the outpost in central Pennsylvania. The birth of their seventh child, Frances, a few months ago makes the decision to again leave Rhode Island that much more complicated. Maybe some day.

Someday comes five years later. Sadly, that’s also when Jonathan dies at the hands of Natives in his new home in central Pennsylvania. Frances will be five at the time of her father’s murder and will spend the rest of her life living as an adopted daughter in a Native Miami tribal household. For the rest of her life her home will be in the territory known as “Land of the Indians”, or Indiana.

The fury of 1773 caught up with young Frances in the woods and her life changed forever.

(Frances Slocum as an adult)

* * * * * * *

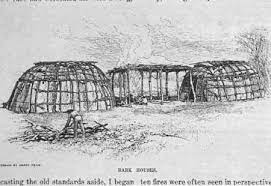

Today, 250 years ago, at a place called “Arkansas Post” where the Arkansas River flows into the Mississippi River, a Native Quapaw chief announces he has a new son, also adopted as Frances will be. The boy is English by birth. Populated by fewer than 80 people, Arkansas Post is a hotbed of intrigue, sitting in a region claimed by the Quapaw and Osage tribes, the Spanish Empire, the French Empire, and the British Empire. Perhaps the most troublesome person is an English woman named Magdelon, who has undefined influence over the Quapaw chief and likely led to his adoption of the English boy. From her wigwam at Arkansas Post, Magdelon, whose name relates to Mary Magdalene from the Bible’s New Testament, seeks to undermine Spanish control of the region. Spanish officials in the southern valley of the Mississippi River detest her.

(wigwams like those at Arkansas Post)

* * * * * * *

Things can shift quickly from out of sight to out of control.

Also

Empires and colonies can crack from different earthquakes.

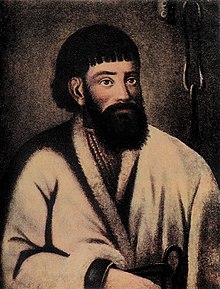

In southern Russia, a revolt rages against Empress Catherine II. Led by Lemelyan Pugachev, a discontented officer in the Russian imperial army, a mixed group of Cossacks, peasants, serfs, and various non-Russians have coalesced into open rebellion against the Empress. Pugachev solidifies his grip on the rebels when he adopted the false guise of Peter III, a figure with mythical prestige and legendary effect. Pugachev/Peter III’s military forces have captured the city of Orenburg. Success there produced more battlefield victories west toward the Volga River and east toward Siberia. Momentum has swung his way by late 1773.

A host of Native groups joined the rebellion as well. Udmurts, Chuvash, Mordovians, Mari, Tatars, and Bashkirs entered the rebellion on the side of Pugachev. For reasons that almost defy counting, the assemblage of rebels encounter both the potential and limitation of diversity.

By now, 250 years ago, Empress Catherine II has begun to realize that the rebellion is a threat and that her military must be overhauled before it can crush the uprising.

(Lemelyan Pugachev)

For You Now

Well, it’s here. We’ve known about the pair of tea-related laws since Parliament’s passage of them in spring, roughly six months before the tea arrives in the British colonies. We’ve known eight ships were sailing the North Atlantic. And now the first ship has entered Boston harbor, the tea on board.

Don’t forget that a crate of Phillis Wheatley’s first published books is also on board. She’s the young and formerly enslaved black teenager who has a gift for poetry and creative writing. Both she and the tea have been the talk of Boston for these past several weeks. The symbolic and symbiotic relationship of the boxed tea and crated books should be much better known as part of the British imperial-colonial story in late 1773.

Incidentally, the name of that tea- and book-bearing ship is the Dartmouth, in honor of the Earl of Dartmouth who many colonists had assumed would be an ally in the upper echelons of the British imperial government. Months ago, the man Dartmouth was the hope of the hour. Now, the ship Dartmouth brings a troubled future. The irony writes itself.

I’ll wager that in the weeks ahead in late 2023 and early 2024 we’ll encounter something similar (as a rhyme) to the irony of the ship name and the symbolism/symbiosis of the tea and books. Quite likely it may take a while for this to be clear but I’ll bet our rhyming versions will one day be evident. They’ll write a book about it.

What stands out to you from today’s Redux entry? I ask this especially if you’ve followed the entries from the past few months and have witnessed the ebb and flow of things as we arrive at the end of November 250 years ago. If this is your first time reading or nearly your first time reading, I invite you to go back a few months and then come forward to November’s end. I’m guessing that you’ll find a notable point within the overall story.

I’m struck by the concentration of attention on what the tea represents and embodies to the protestors. The dried substance carries great weight in ideas, attitudes, and philosophy. The dried substance helps build a platform for actions contemplated and anticipated. The dried substance shines a light on pathways running in opposite directions, from power to rights, from authority to persuasion. The dried substance draws into itself a set of past experiences and a shadow of future possibilities. A galaxy of stars spins out from the dried substance.

(the dried substance)

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider—what do you see in the tea leaves?

(Your River)