Americanism Redux

November 23, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1773

A table with chairs around it. A tabletop with platters of food on it. We sit, eat, and talk together. Not all food will be eaten and not all thoughts will be spoken.

A moment becomes an event. A space becomes a place. Time becomes a light, carried on waves from a darkness above, visible through a lens of happened before.

(Happy Thanksgiving)

* * * * * * *

They sat at table together, today, 250 years ago, to enjoy a meal. Turkey, ham, venison, these were the items often savored when guests came to the “Old Farm” for a November feast. These two men were actual friends, having dug trust and reliability from the flat ground of acquaintanceship and collegiality. They agreed more than not, found each other knowable and reasonable. They knew each had a partial footing in different directions.

Sitting in one chair at table was George Washington. He was a married wealthy planter in Tidewater Virginia, a war veteran-commander, and a failed seeker of an officer’s rank in the British Army, which made him a realist with a memory. Sitting in another chair at table was Lord Dunmore, aka John Murray, Virginia’s colonial royal governor, holder of a British aristocratic peerage, a former British officer who had raided the French coast in the French and Indian War, and former colonial governor of New York before coming to a similar post in Virginia.

In between mouthfuls of turkey, the tablemates could chew on such topics as lands they both coveted in the Ohio valley, Dunmore’s recent purchase of a beautiful second home, and Washington’s extensive agricultural business along the Potomac River. If they dared, in the empty cups on saucers next to their plates, one of them might risk a request for tea to be brought out and poured. If so, however, the table’s talk might turn to the tea itself and then, inevitably, to the East India Company, the Tea and Governing Acts, the eight ships soon expected to bring tea to four colonial ports, and potential reactions by anti-tea protestors. They would find themselves on opposing sides of the argument. The hot tea would turn cold.

Perhaps coffee would be a safer choice for the porcelain cups. Or better yet, maybe port in a glass. There’s nothing political about port, is there?

(Dunmore/Murray)

* * * * * * *

Also today in the colony of Virginia, 250 years ago, as Washington and Dunmore reach for their porcelain cups, another man reaches into a rough cloth sack for food. His meal is pieces of dried and salted pork, chunks of old bread, maybe an apple on the side. He sits on the ground with his back to a pine tree. He chews, stops, listens—chews, stops, listens. Then it’s time to get on his feet, look around, and head out, into the woods.

His name is Burton. He’s 23 years old, just under six feet tall, wearing ragged clothes and a small felt hat with a dark band tied around it. Though hungry from trying to make his rations last as long as he can, Burton feels a tangible relaxation in his face. He’d been used to keeping his face tightened and expressionless in front of his enslavers but now, on the run but totally free in his body up against the pine tree, he chews and swallows without the strain showing on his face. With a maskless face, he’ll continue his quest to make freedom ring.

(like Burton)

* * * * * * *

Further south on the Atlantic Coast, in Charleston, colony of South Carolina, Dillon’s Tavern is the center of 45’s.

45 punch bowls and 45 bottles of wine on the Tavern’s thick wooden tables.

45 men seated in 45 chairs.

45 candles burning nearby.

45 toasts made with loud voices and shaky hands.

All this after a parade involving 45 pairs of legs marching down the street.

Which had been preceded by 45 men standing beneath a tree—the town’s Liberty Tree—with 45 lanterns hung from the branches.

Above them 45 skyrockets were lit and exploded in the air.

All of this was the work of the Club, led by the Rutledge brothers, John and Edward, that calls itself “the 45” in honor of radical British politician John Wilkes who gained notoriety by demanding more freedom, liberty, and equality of power in the British Parliament. Wilkes served time in jail for his views after publication of his newspaper’s 45th edition, the one in which he blasted royal authority. Now you get it—the reason for the “45.”

Starting under the tree, ending in the tavern, the Charleston “45” had publicly denounced British tyranny and later stumbled to home from Dillon’s Tavern. Today, 250 years ago.

(Charleston’s Liberty Tree where the 45 first gathered)

* * * * * * *

Moses Lindo is a Jewish resident of Charleston and had he been in town he would have seen Club 45’s day of events. Instead, he was in London, England, working hard to support South Carolina’s indigo industry in the imperial hallways and manor houses of power and policy. That’s how the game is played—if you have major interests in an economic sector, you go to where the political power is to protect and promote the market, the resource, the product. It’s how the East India Company did it and it’s how a colonial industry such as indigo could hope to go from struggling fledgling to too-big-to-fail.

(indigo)

* * * * * * *

The pot is at the boiling point in New England, today, 250 years ago. Three days prior a crowd of anti-tea people had waited patiently as a 43-page document was read aloud to them—that’s right, 43 pages read aloud—so that they could offer editorial changes. The title hinted at the length: “The Votes and Proceeding of the Freeholders and other Inhabitants of the Town of Boston.” The 43 pages summarized events in the dispute over tea from late October up to now. The document, authored largely by Samuel Adams, consisted of three sections: a statement of rights; a list of the violations of those rights; and correspondence that will be sent to 260 towns and districts throughout the colony of Massachusetts to encourage unity in opposition to the tea.

Three days later, which means today, 250 years ago, representatives from five towns squeeze into Faneuil Hall in Boston. They hear a letter read aloud, which ends thus: “We earnestly request, that after having carefully considered this important matter (the future landing of the tea), you would impress upon the minds of your friends, neighbors, and fellow townsmen, the necessity of exerting themselves in a most zealous and determined manner, to save the present and future generations from temporaly and, we think we may with seriousness say, eternal destruction.” The meeting’s leaders, who include town clerk William Cooper, decide to add a “postscript” that concludes with: “In this extremity we earnestly request your advice, and that you would give us the earliest intelligence of the sense your several town have, of the present gloomy situation of our public affairs.”

Andrew and Katherine Boardman, husband and wife, have heard about Boston’s long document, the letter, and the postscript. They live in Cambridge, near to Boston in the colony of Massachusetts. They are a lively, active, and energetic family with children 23-, 16-, and 6-years old. The Boardmans know that a storm looms on the horizon, its exact size and shape unknown, though its effects on their family will surely be deep and powerful. They will join with their neighbors to “Consider upon measures most proper to be taken at the Alarming Crises.”

Note the plural “es” rather than the singular “is”. It’s precisely right—there are multiple problems that could unfold at a day’s notice and race into many directions.

Meetings. Talks. Discussions. Plans. Ideas. Contingencies. Now. Now. Now.

(Faneuil Hall)

* * * * * * *

George Washington thanked Governor Dunmore for his hospitality. Reaching for his coat and hat held by one of Dunmore’s enslaved servants, Washington bowed his head slightly to the Virginia governor. 250 years ago today, a second meal awaited Washington, this at Anderson’s Tavern in Williamsburg. He swung his leg over the saddle, fixed the reins in his hands, and the horse began to trot.

Clip-clop.

By the time Washington arrived, it would be too late for tea.

Also

Pedro Cortijo is almost crying. He manages to glance at the people around him. Some of them are misty-eyed, too. Cortijo and his friends begin to speak in Latin, in a section of San Juan, Puerto Rico, in this building, the first black-and-native Roman Catholic congregation, parish and community in Puerto Rico. It’s been a long struggle here where Tainos natives clashed with, then lived with, and then mysteriously became one with enslaved black Africans who had escaped from the adjacent Danish-controlled Virgin Islands. The place is now called San Mateo de Cangrejos, after the local crabs that everyone here enjoys eating. As formally recognized black-native Puerto Rican Roman Catholics, it is the first day of who they are, a type and form of independence in the domain and dominion of Spanish empire.

(Pedro Cortijo)

A different mood covers the ground known as Mary’s Point. It’s located on St. John’s of the Danish Virgin Islands and today, 250 years ago, the Klaasen family remembers the same day four decades ago, in 1733. That’s the beginning of a local war, an uprising by enslaved Africans from Akwamu (modern Ghana). The goal of the Akwamu rebels was to seize from enslaving plantation owners and govern the island themselves. A key point in the war was the betrayal of the Akwamu by Franz Klaasen, another enslaved black man whose loyalty was to the plantation owners. After the uprising was crushed, Klaasen received title to land on Mary’s Point, which his descendants still own as of today, 250 years ago. The Klaasen family somberly remember this 40th anniversary. For themselves, they secured their own version of independence while the dreams of self-government by the Akamu rebels lay lifeless in the past.

(Mary’s Point)

For You Now

Sixteen years after his late November meal with Lord Dunmore, President George Washington will announce a day of Thanksgiving to be held on November 26, 1789. He called for the American people to acknowledge “with grateful hearts the many and signal favors of Almighty God, especially by affording them an opportunity peaceably to establish a form of government for their safety and happiness.”

That same year Lord Dunmore will be serving as governor of another British colony, the Bahama Islands, not far from the black-native parish in Puerto Rico and the Mary’s Point property on St. John’s in the Virgin Islands. By then, the parish will still be meeting and the property will still be intact.

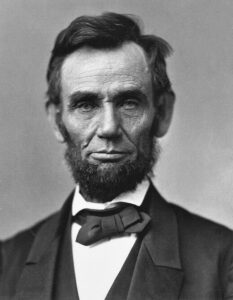

Three score and fourteen years later, in 1863, Abraham Lincoln will purposely re-declare the same thing, this time making Thanksgiving a national day of gratitude. Lincoln noted, in part, “The year that is drawing towards its close, has been filled with the blessings of fruitful fields and healthful skies. To these bounties, which are so constantly enjoyed that we are prone to forget the source from which they come, others have been added, which are of so extraordinary a nature, that they cannot fail to penetrate and soften even the heart which is habitually insensible to the ever watchful providence of Almighty God.”

In both the day of Thanksgiving’s announcement and the day upon which Thanksgiving would be scheduled, Lincoln consciously followed the example of Washington.

At any one of a million moments between Washington and Dunmore’s casual meal in 1773 and Lincoln’s Thanksgiving declaration in 1863 things could have gone differently, the River of Life take another turn. Washington might have altered his loyalty to the British Empire to fit his friendship with the British Governor. Dunmore might have offered him an opportunity, and thus a future, to which Washington couldn’t say no. That takes us to a count of 2 with 999,998 other moments to go.

Maybe we should be thankful that things turned out the way they did. And for those aspects of the turning-out that have proved less than ideal—indeed, may have proved downright nasty—well, then it’s our responsibility and our charge to make it better next time. In so doing, we’ll ensure that someone in the future is thankful for us.

(1863)

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: What’s the most important reason for the American people to be grateful this Thanksgiving?

(Your River)