Americanism Redux

November 2, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1773

There might be one thing that you truly would never, ever give up.

* * * * * * *

Dr. John Connolly is doing today what he loves doing most, adventuring on a river, seeing the prospects of a new life, absorbing the implications of lost worlds and how the world of now came from the world that was. He knows this place well, the watery routes east and west, the animal paths made over the centuries, the villages of Natives, many of whom eye him with suspicion and distrust. He also knows that a rival group of people like him, British colonists one and all, have their sights set on this place.

He is on the Ohio River, near its junction with the Scioto River, new owner of 2000 acres in this region, granted to him by Virginia’s royal governor, Lord Dunmore. But there is more than one British colony and more than one British colonial politician or political body with the self-proclaimed right to take and distribute these lands. A fight is ahead.

Connolly likes the Virginia governor. He senses a kindred spirit who is willing to be aggressive in getting what he wants and will use force if necessary to do so. He sees a clear and appropriate line running from King George III to Governor Dunmore to local supporters of British imperial interests such as himself. He also knows people like George Washington; the two have met and share a mutual liking and respect. Still, Connolly looks at Dunmore and sees the future he prefers. For King and Country.

Up the river comes a chilly breeze, striking the 30 year-old Connolly’s face. He’s felt breezes before in the Caribbean Sea, along the Atlantic coast, and off the Florida peninsula. Today, the Ohio’s wind carries the smell of falling leaves and woodsmoke.

* * * * * * *

Today, 46-year old Eleazer Brooks sits down at a table with two other men in the meeting house of Lincoln, colony of Massachusetts. He and his two colleagues are now the town’s Committee of Correspondence to seek and share information in support of colonial rights. Today, November 2, is the CofC’s first day of existence. They call Brooks “Captain”. He’s in charge of the town’s militia unit, a group of men and boys who serve voluntarily in this community group, turning out for an alarm, an emergency, a local crisis. Less than five miles away from the table at which Brooks now sits, a small wooden bridge spans Concord River in nearby Concord, Massachusetts. The bridge is empty and the river is cold.

(a local home that Brooks knew)

* * * * * * *

East of Brooks’s location is Marblehead, again in the colony of Massachusetts. Don’t go there today, or, if you have to, be forewarned—everyone at Marblehead is angry, upset, resentful. No, it’s not about tea and British imperial-colonial relations. It’s about disease and its treatment, specifically, smallpox and inoculation by injection. For the past two weeks a new privately-built hospital has opened. Patients are arriving in the town. A fight has broken out about the new hospital and where you stand in the brawl will be shown by what you call the facility—supporters refer to it as “Essex Hospital” while opponents refer to it as “Castle Pox.” A lot of things are entangled in this local civic war, from social status to length of family residency in the area to economic wealth to attitudes about science and wellness. The dispute is fierce and sucks in the energies of many people in this seafaring town.

(Marblehead, center of town)

* * * * * * *

The young children shuffle in the wooden benches. They’re leaning forward, hands and elbows and arms on the desks in front of them. Nervous, excited, maybe scared, too. At the front of the room, which is to say the front of this one-room school-house in East Haddam, colony of Connecticut, the lectern where the teacher usually stands is empty. But just wait, give it a minute, maybe less, counting down from twenty to ten seconds, from ten second to five, four, three two, and one….

And the students turn to see their new teacher enter the room, walk to the front, and stand behind the lectern.

Say hello to 18-year old Nathan Hale, East Haddam’s newest educator, full of promise and potential, vigor and vibrancy. His life shines as bright as the yellow leaves clinging to the maple trees right outside the school-house.

Another group of children sit in their seats waiting for their teacher. The students are related, brothers, sisters, cousins. They’re the Carter family on the family estate in northern Virginia, Nomini Hall, owned by Robert Carter III. The Carter children’s teacher is on his second day of work, 26 year-old Philip Fithian. His eight students—five boys and three girls—range in aptitude from reading and writing Greek to reading and writing the ABC’s. Fithian says “the place (is) fully equal to my highest expectations.” The Carter home is Virginia luxury at its finest, the opposite of Hale’s modest teaching space in small-town Connecticut.

As teachers, Fithian and Hale have started their lives in widely separated spaces. In the future, their students will follow vastly different pathways into adulthood and civic life. In four years minus one month, in the fall of 1776, Fithian and Hale will encounter death in the war-torn region of New York City. Fithian’s last breath will be on an American military cot, his life stopped by a killing fever. Hale’s last breath will be at the end of a hanging rope, his life—the one he regretted giving as an individual man—stopped by the British for his work as an American spy.

(Nathan Hale)

* * * * * * *

Broadly speaking, the topic of learning occupies the thoughts of Juan Antonio Cervantes in Tempoala in the Vera Cruz province of Mexico, New Spain. He has been watching the small settlement of Yamasee Apalachinos, the Natives from Pensacola in the British colony of West Florida who’ve been forcibly moved to a site near Cervantes’s home. In his opinion, the relocated Natives are too dissimilar to the Spanish and Mestizo colonists like himself. They don’t farm like him, don’t agree on owning land like him, don’t spiritually worship like him. They’re not going to learn our ways, concludes Cervantes. Cervantes knows that Natives elsewhere in New Spain have actively rejected Spanish ways and are revolting against imperial authority. Will the day come when the armed uprisings and reprisals explode around his home? And what is the calculus of how people live together, their bits of sameness and shards of contrast. What if the thing being taught is the thing no one wants to learn?

(A Yamasee scene, prior to removal to New Spain)

* * * * * * *

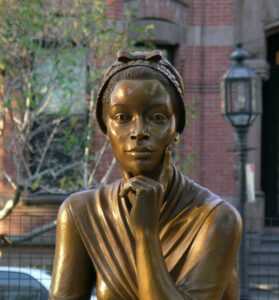

Phillis Wheatley, the young black female poet, is back in Boston after a life-changing visit to England. She is now free, has published a book of poems, embraced the hospitality and well-wishes of numerous Englishmen and women, and is seeing a larger circle of friends and acquaintences interested in her writing. More people know who she is. She worries that success could make her self-centered and self-absorbed. She’s also been thinking about the story of Esau in the Bible, seller of his birthright to his brother Jacob in exchange for food. Phillis warns her dearest friend “not to sell our Birthrights for a thousand worlds, which indeed would be as dust upon the Ballance.”

Living as a frail child in central Africa. Captured, enslaved, and sent to the New World on a slave-trading ship. Living in New England with an enslaving husband and wife. Learning to read, write, and create in her writing. Back across the Atlantic to England, and then back again to New England. Now freed. And at 20 years-old she’s thinking about “Birthrights” and the spiritual teaching that they must be held, kept, and retained at all costs.

To the end of time.

(Phillis Wheatley)

* * * * * * *

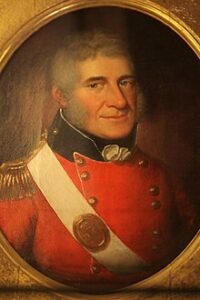

A grizzled Redcoat officer, Frederick Haldimand, of Swiss birth, sits with a stack of newspapers on his desk. He’s in his military quarters in New York City, commander of a small British military force stationed there. He’s read through the newspapers—from New York and other places—and has reached a conclusion: “some opposition will be made to the Importation of the Tea to be sent by the East India Company.” And there’s more:

“I shall endeavor to prevent it as far as will appear consistent with Prudence in the present State of Affairs in America.”

(Frederick Haldimand)

Also

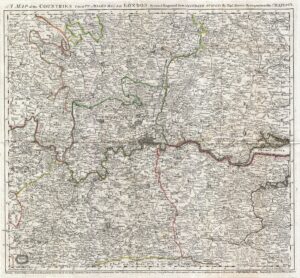

Sit with two men in London.

(1773 map of London and 30 mile environs)

Benjamin Franklin is staying in the British imperial capitol for another year. He decided not to return to America. He senses support for the colonial situation among England’s influential people, especially those with economic interests tied to the British colonies. A tide could be turning in the colonists’ favor, which in his opinion has been nudged in the right direction partly by his public writings in London’s newspapers. Maybe, Franklin thinks, his suggestions are finally changing people’s minds. Further, Franklin believes the wisest thing is to push the issue of rights, be they colonial or imperial, into the background. Economic interests will be a safer platform for discussing change and making reforms. Economically-based decisions can be produced if the explosiveness of rights can stay contained. Franklin shares these thoughts in a letter to Thomas Cushing in Boston, formal leader of the Massachusetts colonial legislature. He assures Cushing that he’ll write again when the next Parliamentary elections are done (his next letter is two months and two days later, on January 4).

It’s a viewpoint similar in tone to a second man in London, Lord North. North is the prime minister of King George III’s imperial government. Barely a few months ago North was mired in political difficulties with no way out. Now, miraculously, North feels bolder, stronger, optimistic. The Tea Act and its companion Governing Act have resolved the crisis of the East India Company. He’s happily facing the prospect of elections “that will make it necessary for us to look to ourselves and to secure our majority by every legal means.” The election will come soon enough and with it, a new majority ready to work out imperial-colonial problems. Until then, North is eager to sit back and enjoy some of the financial gains that attach to his position.

Franklin the American and North the Briton speak from comparable outlooks. They’re upbeat and confident. They smell a positive change in the wind. Yes, circumstances in imperial-colonial relations are far from perfect. Improvement isn’t far away, however, and the turning of the calendar from 1773 to 1774 will be good timing for starting fresh to make things better.

Stoke the fire for the approaching winter. Find more blankets for longer and colder nights. Brush off the frost and wait for snow.

For You Now

Remarkable to witness the exchange between Phillis and one of her closest friends, two young black women who speak so passionately about “birthrights” and their determination to never surrender them…again. They didn’t have a choice the first time around, inland from the African coast. They’ve persevered since then and have grabbed birthright with both hands.

Interesting to think about the two young black women in light of Franklin’s latest thoughts. He wants to go quiet or at least be less noisy about “rights.” They wouldn’t consider it for a moment.

The optimism and buoyancy of Franklin and North also do not fit with the darker insights from the soldier Haldimand. He’s not seeing much cause for hopefulness as he looks outside his quarters at his version of ground zero. He’s picking up tensions in the talk and mannerisms of people on the streets of New York City. Mixed with his observations is a self-imposed limit—prudence. He doesn’t want to make things worse.

They’re all dealing with a relationship between present and future. Haldimand’s perspective is that the relationship is micro at most, divided by seconds, minutes, hours, and days. Franklin and North’s perspective is that the relationship spans weeks and months. Franklin and North are always catching up with quill and paper while Haldimand is always fighting fires with buckets of prudence.

The pair of young teachers are trying to prepare their students for adult life and the future. The children have no idea that both adulthood and time ahead will have a cataclysm that destroys each of their teachers. And if you knew the present yet to come, what would you want them to be learning now, before such a present arrives?

Sometimes proper learning isn’t enough for the future. We’re occasionally unfit, not ready for the future in front of us. That was so for Dr. Connolly. Thirty years too early: Dr. Connolly is born thirty years too early…and with the wrong thought in his head. A younger Connolly would have been a perfect fit for the Lewis and Clark expedition thirty years in the future. He was all skill and experience and curiosity, capable of thriving in the outdoors. But perhaps more than his birth year thirty years too soon, he had a mental affinity for monarchy, a rigidly ordered society, and a government of rulers and ruled that would have blocked his access to the mission and adventure of 1803-1807. He wouldn’t have embraced the people and nation that made the Corps of Discovery. But at least now you know his name.

And then there’s the future where the past is already there. See the hospital of Marblehead, where a killing sickness carries with it a fight over treatment. Illness does its work while people bite and thrash.

But at least you know what that’s like.

(a British colonial home in late autumn)

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: do you believe in birthright?

(Your River)