Americanism Redux

May 4, today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1773

There goes one. Gentle in the air. Falling, drifting onto the bright green grass without making a sound. Delicate and soft in its color and shade. The breeze carries it down. These are the blossoms of the fruit trees, descending one by one after a week of brilliant fragrance. They’ll begin to decay.

(blossoms strewn)

Songbirds hop from branch to branch—cardinals, meadowlarks, chickadees, orioles, and goldfinches. Occasionally a bird will fly from the branches and land on the grass. The bird searches for worms and insects. It pecks at the ground amid the fallen blossoms.

For the many cattle and horses seen across the river valley, the thick grass will make for fine grazing.

Neatly tended houses and barns dot either side of the road leading to Philadelphia.

About ten days ago Josiah Quincy II had traveled this road in his journey to this most prosperous and advanced community in the thirteen British colonies, in British America. He went as far south as the Carolinas and is now on his return home.

He visits, listens, and observes. He worships and anticipates. He remembers and reflects.

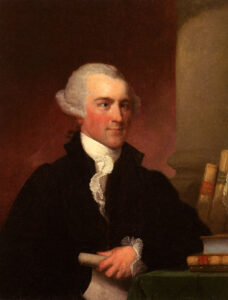

(Josiah Quincy II)

* * * * * * *

He’s been traveling throughout many of the colonies south of his native Massachusetts. Why? Quincy believes strongly in colonial rights and opposes British imperial power. He wants to know more about the people south of New England who also support the colonial cause. He’s investigating.

The Cause. It’s the most important thing in public life as Quincy understands it. He’s also principled, having joined with John Adams three years ago (1770) as the lawyers who represented British Redcoats charged with killing five colonists in the Boston Massacre. The King’s soldiers, the team of Quincy and Adams had argued, had deserved a fair trial with competent legal representation. The Quincy-Adams team succeeded in defeating the charges against the accused soldiers. The Redcoats went free.

That’s the kind of person Josiah Quincy II is. Of honor, integrity, conviction.

His time today in Philadelphia has been as rich and absorbing as the rest of his southern journey. Today, 250 years ago, he meets for two hours with the wealthiest man in the city, Chief Justice William Allen. Allen leans toward British imperial power and away from the pro-colonial rights movement. Allen has told Quincy that Benjamin Franklin is dishonest, a sneak, a climber who scrambles up the next rung of the ladder with no regard for truth. Allen elaborates: Franklin is also the secret promoter of the Stamp Act back in 1765 that was the first real explosion in British-colonial relations. Quincy is convinced. He concludes, “I find men who are very great foes to each other in this province, (but) unite in their doubts, insinuations, and revilings of Franklin.”

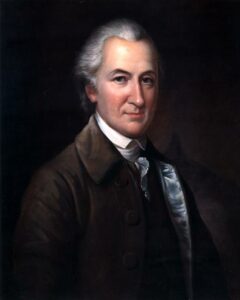

Quincy is also convinced that yesterday he met likely the most famous man in the entire British-colonial dispute, John Dickinson. He’s the author of “Letters From A Pennsylvania Farmer” back in 1768 where he argued on behalf of both the colonial cause as well as restrained protest. No one involved in the Cause has not heard of Dickinson and his signature booklet. Up and down the Atlantic Coast, Dickinson is celebrated among pro-colonial supporters. He’s got it all, according to Quincy: “the antique look of his house, his gardens, greenhouse, bath house, grotto, study, fish-pond, fields, meadows, vista, through which is a distant prospect of the Delaware River, his paintings, antiquities, improvements, in short, his whole life, and we are apt to think of his (as) the happiest of mortals.” However, Quincy suspects Dickinson is privately unhappy. Something about him raises suspicions in Quincy’s mind.

(the famed John Dickinson)

Dickinson tries to give Quincy a bound copy of the “Laws of Pennsylvania.” Quincy refuses politely the gift of the books.

At meals with community leaders Quincy has talked at length about politics and British-colonial tensions. He senses Judge Allen’s hesitation, analyzes Dickinson’s opinions rooted in the implications of his vast comfort, and embraces the notion that Franklin has unperceived motives and ambitions in the simmering times.

Philadelphia is the most prominent place in British America as a living space of gathered people. And Josiah Quincy II has today, 250 years ago, collected his thoughts about some of the city’s leaders and what they portend in the current state of life.

Also

When you try to understand a place of people, what else do you look at?

Quincy looks at the world above him—in other words, spirituality. He’s a member of the Congregational Church in Boston, a Protestant believer in God, Christ, and the Holy Spirit. In Philadelphia he attends a Moravian church and is appalled by a structure too basic for him. By contrast, he attends a Catholic Mass in the community and gushes, “In me the fire enkindled is.”

He also watches out for appearances—the tidiness of streets, the harmony of design of roads, and the condition of houses, homes, and buildings.

He notes the pleasure of the company he keeps, especially in conversation and dialogue. He remarks favorably upon the presence of live music at dinner.

He tours one of the community’s most advanced and innovative institutions, the College of Philadelphia. Afterwards, Quincy asserts that the reputation is undeserved, the college an empty shell.

(Elfreth’s Alley, Philadelphia)

For You Now

People living in a place. They are the engines of what will happen. As individuals, formed collectively into families or other groups, or joined within institutions and organizations, these people are the resources through which life finds itself. They are the change and they are the continuity.

Josiah Quincy II is gauging things. He wants to know the depth of commitment to the Cause among people he’s never met in places he’s never been. A day, a few days, a week, or in the case of Philadelphia, maybe more, Quincy is all eyes and ears so as to take in every ounce of information and impression before arriving at a conclusion or judgment.

He’s filtering everything through the experiences he’s already had. He may not even know—indeed, certainly doesn’t and cannot know—the extent to which his filters are shaping his conclusions and judgments. And when he reports to his former courtroom colleague John Adams or other people in the Cause, they’ll be equally in the dark as to the border within Quincy separating objective analysis and subjective assumption. The line between will waver, both visibly and invisibly.

This is as true for you in 2023 as it was for Josiah Quincy II today, 250 years ago.

Suggestion

Consider this: is there an American community you want to visit to help you gauge where the nation is now and where it seems to be heading?