Americanism Redux

March 9, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago today, in 1773

It’s one of those days. Nothing special on the face of it. Life sprawls, today, 250 years ago.

(Ordinary Day, sunrise)

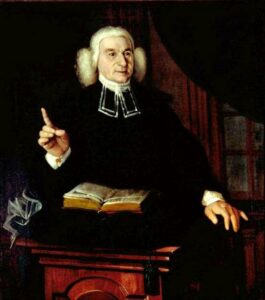

You see kindness. A Christian pastor travels from house to house in Westborough, Massachusetts. He’s visiting members of his congregation who are sick. A young boy, Willard Miller, is very ill. The pastor prays with Willard and his parents. Speaking of pastors, in Williamsburg, Virginia several preachers are planning to meet to raise money to help widows and orphans of pastors who have died recently. Any donation is welcome.

(Reverend Ebenezer Parkman, he held hands with young Willard Miller)

You see harshness. Unnamed men, women, and children from “Palatine”, a German region, have landed in Philadelphia. Stepping off the ship, Enoch Story was there to grab them and hustle them off into a house. He’s got them barricaded there. He’ll take cash or credit to anyone who wants to “hire” them as workers. They don’t speak English and are terrified out of their minds. Not far from them, Benjamin Bannerman waits for people to answer his ad. He’s looking to buy any enslaved black person between the ages of five and forty. As they’re brought in, he’ll cram them into a “holding space” where other shoppers can come by and inspect them. He’ll resell for cash or credit. No questions asked in the city of brotherly love.

You see memories. In Boston they’re still talking about last week’s third-anniversary commemoration of the Boston Massacre. Sure, the speech by Benjamin Church was good—it’s soon to be printed and sold—but the main topic is the “transparent paintings” that were created by artists and then hung from a balcony, and made to walk back and forth with sounds and voices added. This night-time, torch-light re-enactment of the Massacre thrilled the crowd. Like watching moving pictures on some sort of three-dimensional screen. It was chilling, eery, out-of-body. They could imagine being there three years ago.

You see weirdness. Dr. Graham is in Philadelphia gearing up for a performance. He’ll give a one-night-only lecture on the human eye. He promises to astound, inform, and shock the audience. Get tickets as soon as you can.

You see hints and traces. Robert Aitken wants to launch a new publication entitled, suggestively, “The General American Register.” Born in Scotland but now calling Pennsylvania home, Aitken expects “American gentlemen” will want the annual publication for easy access to the knowledge that makes them successful. Note the word: American, a term embraced by this adoptive-home American. Note, too, that John Rogers in Connecticut detects that “a Military Spirit seems to be recovering in this Colony” and he’s seeking to take advantage by selling “Military Drums” to gentlemen organizing groups of armed volunteers. In Salem, Massachusetts a likeness of British King George III hangs on a sign above a new tavern. The owner hopes it will bring in customers with a thirst. Would a day ever come when he changes the sign?

(Robert Aitken)

All of this is a jumble, to be sure. Life going as it goes, unrelenting, undeterred, uncontrolled. Not easy to see how one event or another might tilt or shift the jumble into something else. But whatever else will be true, it’s a higher truth that life is taking a thousand directions in a single day. The event that collides with life will collide with those thousand directions. Will it invisibly disappear in the mix? Will it change the mix?

Also

Jumbling the jumble are the people supposedly holding positions of responsibility and authority. Today, 250 years ago.

In Mexico mid-level officials are bickering. They jockey for advantage in a hybrid governmental and religious bureaucracy, each seeking to gain at the expense of the other. One of them—Rafael Verger, who we’ve seen before last November in writing two-dozen recommendations for improved colonial administration—is back at it again. On the surface, he’s got a good idea: he wants another official, Junipero Serra, to provide a list of vital items, policies, and actions for effective colonial control of land from Mexico northwest to the Pacific Ocean. Sounds desirable, right? Not so fast. His motives aren’t great; he wants to put a competing bureaucrat in a bad light and the list could help him do it. It’s a chess-game, essentially, and it may not even be that noble. The right steps with the wrong motives lead to ragged outcomes. A broken wheel doesn’t take you anywhere.

(Rafael Verger)

In the British colony of North Carolina the imperially-appointed Royal Governor Josiah Martin and his executive council (upper chamber of the colonial legislature) have agreed to send everyone home. Everyone, that is, who occupies an elected seat in the General Assembly, or lower chamber, of the colony’s government. Not enough of them here to debate and enact any laws. Go home and we’ll call for another election. Whatever world-changing issues—yeah, right, that’s what they always are—which were to be settled will just have to wait. Doing nothing is the only action until further notice. Bump and bounce and drag along.

For You Now

It’s an ordinary day, which calls for extraordinary judgment. Let’s give it a go. You and me.

To start, the small stuff may not be as small as you think. Look at John Rogers and his decision to sell military drums. There’s been no violence or serious threat of violence in Connecticut for eight years (1765); the colony’s most famous soldier, the irregular fighter Israel Putnam, hasn’t even been there for weeks because he’s on a settlement-discovery voyage in the Caribbean Sea. And yet, Rogers thinks the local market will respond to his sales of military drums. Rogers is picking up on a sense that armed conflict—specifically, the preparation for armed conflict—is on the rise. It’s one piece of evidence we have for the tenor of the times, and the change in the tenor, in March 1773, at least in Connecticut. How deep does the feeling go? Is there a way to bend it in a different angle or direction? Will the rise fall back?

The same goes for Robert Aitken in Pennsylvania. He believes there’s a readership market among an American-oriented class of successful men or success-seeking men. Not British, not imperial, not colonial, but American. Is it too late to develop a more British/imperial focus for self-defined successful men in the most vibrant and innovative community in the American colonies? What would it take? Is it really any concern if it’s American or is that simply no big deal?

Think about the recollections of people in Boston. They’re remembering a few days’ back, the Massacre ceremony last week. Colonial rights advocates have been using the ceremony to keep the memory of the 1770 Massacre alive; last year’s keynote speaker wore a toga in imitation of an ancient Roman senator. What gimmick will it be next year? Live ammo in the muskets and fake blood smeared on pretend victims? The advocates keep stoking the fire, keep adding fuel to make sure the flame doesn’t die out. How long can they keep the thing burning? Will the sales of Church’s printed/bound keynote speech suggest anything? Or do we have to dazzle the people to keep them engaged?

And then there’s the issue of forced labor. It takes many forms; it’s on a spectrum. But who will deal with Enoch Story and Benjamin Bannerman and the hundreds of forced-labor purveyors just like them, to say nothing of the tens of thousands of people—a meaningful percentage of the overall population—who keep them in business by action or attitude? To tackle the issue of forced labor will require maximum effort by people in positions of authority, power, influence, and persuasion. They’ll need cohesion. They’ll need a change in a myriad of things, not least of which is their hearts.

What can we say of them, of this hopefully cohesive group who will need to exert maximum effort? Well, on this ordinary day we see a different nation’s colonial world (Spain, operating colonies in Central America and southwestern/west coast North America) and officials there are seeking to poke and jab each other with good ideas unlikely to be done. Further east, in North Carolina, we see a colonial government that can’t operate at all because not enough of the elected representatives show up to do their public duty.

The ordinary day has extraordinary implications, after all.

Suggestion

Consider your current day’s version of the military drums, the newly available periodical, or the image on the sign above the tavern door. Are you seeing small things that leave you with a clear impression of the year’s direction?

(Ordinary Day, sunset)