Americanism Redux

June 1, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1773

The world is a place where horses scream.

From terror, panic, uncontrollable fright. Brought on by a penetrating strike into the deepest instinctual sense of self-preservation. The final breath of death that closes what began with the first breath of birth.

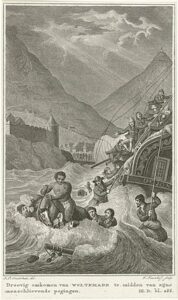

This horse screams as the weight of six men pulls it down, pulls it under, into the freezing salt water off Africa’s Cape of Good Hope.

It was the animal’s sixth trip into the crashing surf, pushed on by its rider, Wolraad Woltemade, who had decided to do what he could to rescue the sailors clinging for life on the wreckage of the Dutch ship “De Jonge Thomas” on the rocks of Table Bay. Woltemade is 66 years old, a retired employee of the Dutch East India Company (yes, there are two, Dutch and British) who was now a dairy farmer. He’d demanded his horse’s obedience—go into the lashing waters, toward the stranded men, let one or two men at a time leap from the broken boards and grab the horse’s tail to be dragged back to shore through the deadly surf. Then let’s go get the next one. Thirteen men are saved this way. On the sixth trip into the realm of Poseidon, men could stand no more and when horse and rider appeared, they lunged through the air toward the horse. With hands clawing at its body and tail and mane, with salt water heaving upward over mouth and nose and eyes and ears, the horse screams until death smiles. All sink below the roiling surface. People watch from the beaches.

(the scene at Table Bay)

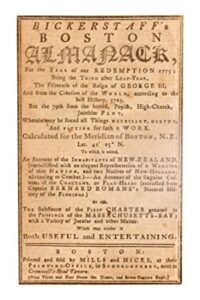

On the world’s other half, near a different ocean, in Boston, ready for sale today is an Almanac where you can read about the tides, the moons, the weather, pithy sayings, recipes, health and wellness advice, farming techniques, and almost anything else you can think of. It’s informative, quirky, suggestive, and really a true bit of fun to read. Not too demanding while still being compelling. The Almanac as a literary product is sort of an invention of Benjamin Franklin and has helped him gain recognition throughout the British colonies. On the front cover of today’s Almanac will be a printed image of British King George III. It’s one of those things that’s a present but invisible reminder—evident only when you stop and think about it—of who we all are, where we all live, what we all seem to believe. When you don’t see them anymore is when you know a fundamental change has happened.

(a Boston Almanac in 1775–notice who’s not on the cover)

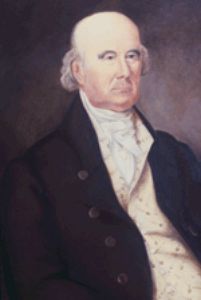

There’s nothing invisible about what 48-year old Jacob Ehrenzeller will do today. He’ll have words on a paper, obligations spelled out, expectations firm and fixed. The future; it’s the day when the future begins for his 16-year old son. The elder Ehrenzeller has a talent for helping people heal their bodies. Back in his native Switzerland, he had attended medical school and down to this very day in the most innovative city of North America, he gives medical advice to people, to patients, who come to him in the tavern that he currently owns and operates. So, today, 250 years ago, Jacob the Elder meets with leaders of Pennsylvania Hospital, the continent’s first formal facility for healthcare services—Benjamin Franklin is among its founders. Jacob the Elder and the hospital’s leaders sign a document today that bounds Jacob the Younger as an indentured apprentice to the hospital for a period of five years and three months, during which he WILL NOT have sex, play cards, or buy personal products or items—and the father pledges the son won’t escape. He WILL be allowed to hear doctors’ lectures, attend surgical operations, and receive training in medical diagnosis and surgery. All of which makes him the first medical resident in the continent’s history. Today, father signs, son nods, and the River flows ahead to tomorrow.

(Jacob the Younger in older age, as a doctor)

Also

The world is a place where some people draw not words but lines on paper. And the lines can change life.

Today, drowning in debt, most members of the Cherokee and some members of the Muskogee native tribes accept obligations written on paper. The natives are struggling with debts built up for a lifestyle they’ve slipped into. They’ve become accustomed to such things as thick blankets for cold nights, paint for facial art, sturdy pots and pans for cooking, beads for fashion and artwork, guns and ammunition for hunting, and rum for relaxation and, sadly, addictive escape. To pay for these items furnished by British and colonial traders, the natives have, year-after-year, tried to pay in deerskins—a practice that has invisibly taken on the image of money, the “buck.” But the deer population is unpredictable and, now, dwindling. The natives’ preference for the items, however, has only grown. The only thing left is to give up land to pay their debts. Today, they agree to abide by a treaty called Augusta in the British colony of Georgia, surrendering two million acres of land to Georgia’s colonial representatives for paying off native debt.

The cartographers will redraw maps of the dry land affected.

(a trail inside the ceded land)

For You Now

Dying to save the lives of others.

The far-away image on a guide to practical living.

A parent frames a child’s future.

A lifestyle preferred feeds a debt unsustainable.

On a single day we see a thing here connected to a thing there. Our four stories: life-saving and death-making; practicality immediate and symbolism distant; plans in the present and goals in the future; and possessions owned and payment owed. Each is a pair and a pair implies connection.

The connection is the crux of it. Does the connection represent a smooth or natural linkage, an organic fit? Does the connection embody a clash where, for a second, opposites dangle in balance but feel destined toward imbalance and destruction? Does the connection point to the temporary and occasional or the permanent and eternal? Does the connection promote a start or an end? And does the connection speak of true for the time or truth across time?

Suggestion

Consider a pair of thing-here and thing-there that expresses a key point about who Americans are right now. Remember that in so choosing this pair, you need to know the nature of the connection within the pair itself. And do the same consideration for who you are as an American.

(thing-here and thing-there and the river that connects them)