Americanism Redux

July 13, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1773

Nemisis.

That’s his name.

(the mountain of Nemisis)

He was left, left around here somewhere on this rise of land in the thick, dense forest. His comrades told him they would hide him so the Natives he’d been fighting wouldn’t come back and torture him to death. They placed a slab of bark from a hardwood tree over his bleeding body laying on the ground. An act of help. “Don’t want it,” he said, stretched flat on the ground, throwing and kicking the bark aside. The pain inside him snarled in seering terms as the bark landed back in the bushes. He growled, heavy of breath and drenched in sweat, “I’ll die soon ‘nough and that’s good ‘nough for me.” It was sneer and statement all at once, a declaration of final independence for the fatally wounded free black man known as Nemisis. Above him, the oaks and maples and elms stared down. Their branches held the birds.

That was in 1756, when he lay wounded from a ferocious battle fought against Native tribes during the French and Indian War, in these woods, ridges, and ravines southeast of Fort Pitt (modern Pittsburgh). A gigantic man, Nemisis was the most feared soldier in his British-colonial military unit. Shortly after the war, the people who’d begun to move into this part of southwestern Pennsylvania began to call the rise of land where the tossed bark lay in the brush and Nemisis decayed, Negro Mountain (unsurprisingly, they’re still arguing in 2023 over what to call the place).

Today, 250 years ago, Negro Mountain sits within a new home-name. It’s Turkeyfoot Township, carved out of Brothervalley Township in Bedford County, Pennsylvania. The names deceive in their sweetness and quaintness. Twenty families live here now—seventeen years after the dying Nemisis threw off the bark covering his torn body in the world war of 1754-1763, and merely nine years after a Native war in 1763-1764—in this land of war and struggle and raw living, a New World foreshadowing of a future British Prime Minister’s phrase of “blood, toil, tears, and sweat.” They’ve moved in from the British colonies of Maryland and Virginia after having moved over from Wales, Scotland, Ireland, and other places in northern Europe. They fight Natives, they fight the woods and land, they may fight each other, they fight life until, like Nemisis, they meet the moment of death. Today, 250 years ago, Turkeyfoot Township is a new-born in the world, writhing, bloody, and bawling with potential.

While they’re coming together in the new township of Turkeyfoot in the Pennsylvania woods, another group comes together along the salt water of Boston, Massachusetts today, 250 years ago.

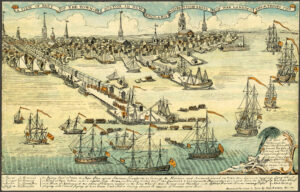

(somewhere in there is the floating shop of George Fetcham)

These names seem to pop up a lot on the same sheets of paper and today is no different—Samuel Adams and John Hancock, along with more than fifty other people who have coalesced over the cause of American colonial rights. But today’s petition to the Suffolk County justices of the peace and the Boston town selectmen isn’t a rebuke about British imperial laws (trade rules) or practices (appointing judges) or personnel (Governor Thomas Hutchinson and Lt Gov. Andrew Oliver). No, today’s petition is about asking for help for an elderly man. They want to help George Fetcham who is too frail to continue his lifelong work as a shipwright—master naval carpenter—but who wants to support himself and not be a burden on his family, friends, or neighbors. Fetcham’s idea is to open a small shop aboard a small ship docked in Boston harbor. From his floating shop he’s planning to sell “a few necessary Articles of Life to the Neighborhood” and, remember the key word is “necessary”, he’ll sell liquor to local boatmen and dockworkers. The inference is that the liquor will make or break the shop’s chances. Adams, Hancock, and the other fifty signees are urging official approval of licensures for Fetcham’s enterprise. It’s a local transaction for local people through local mechanisms. In a way, it’s an oceanside version of what Turkeyfoot wants to become.

Oceanside, or nearly so, in London, England sits sixty-seven years old Benjamin Franklin.

(Franklin’s newly re-opened house in London)

Wispy gray hair falls on his collar. Spectacle glasses rest on his nose. His body, tall at six feet and athletic in build, is stuffed into a wooden chair that creaks when he moves. He’s writing a 3000-word letter to William Franklin, his son by an unwed mother other than his wife Deborah, the name hidden from prying eyes, a concealment lasting far into the future, much longer than the hardwood bark over Nemisis’s body.

The letter is, as they used to say, a tour de force. Father Benjamin guides Son William through his beliefs about the right of revolution in changing from one society to another. He also describes his views on the role that land ownership has in such a change, especially in land shifting from native to newcomer and the newcomer’s rebirthed condition of society. Franklin writes derisively of the British monarch’s decision to curtail purchases of Native land in America. He redirects his letter from here into a reflection on various politicians and political influencers he knows, giving the feel of an instructional manual for navigating the waters of political power. At length he writes of men and women he has met recently, their conversations and the places of dialogue and how each fits into a relational tapestry. He tells in sympathetic tones of an enemy of his, an anti-colonial rights imperial official named Hillsborough, showing the approach to such people without the result of self-destruction. And along the way, he inserts a quote from literary expert Alexander Pope, a pinch of spice in the 3000-word stew. Who knew a parchment letter served as a hearty meal.

Newspaper readers in London are finding out for the first time that a group of “Patriotic” legislators in Virginia have formed a “Committee of Correspondence” to “Superintend” laws from Parliament. It’s a brief report that takes barely a minute to peruse and will only mean more than a minute’s thought if the reader has a wealth of prior knowledge. What does “superintend” suggest?

(source of the bit)

The short bit of strange news, the exhausting letter, the friendly petition, and the newly birthed place with the storybook name and the mysterious mountain are all today, 250 years ago.

Also

Four men have combined to produce a 30-page history of chillingly dramatic proportions. The problem is that it’s entirely factual, or fact-based, and the history is as recent as the day before yesterday, which means that the fire is still burning and could be getting worse.

Josef Fayni, Antonio Maria Bucareli y Ursua, Domingo Xinaga, and Franciso Xavier Balenzuelas write the true story of a rebellion in Durango, Mexico of New Spain. Natives have joined with renegades of mixed ancestry to launch a war against Spanish colonizers. Calaxtrin, an Apache Native, is their leader and the tactics and strategy of his forces are stunningly effective. They use drugs—peyote—to attract new recruits to the rebellion, a technique that has worked well with the Tarahumara. The rebels conduct trade to acquire weapons and intelligence. A true threat exists that might overthrow Spanish governance in the Durango region. The four-man writing team hope to hear of changes to help address the uprising.

Fayni is skilled, almost without peer, in his ability to collect detailed information about on-the-ground reality in New Spain and to oversee its conveyance to imperial authorities in southwestern Europe.

(Calaxtrin’s tribe, the Apache)

For You Now

We’re seeing two versions here, aren’t we? We have the British and the Spanish. Two very different cultures and sets of decisions and actions. Two different pathways of information-gathering. Two different types of consequences and results from imperial authority overseas to colonial reality distant in time and space.

They do overlap. Enslavement exists in both, as do defined roles and status for men, women, and children. Troubling relations with Natives exist in both. Frames of governmental structure exist in both. Officials trying to do a job and locals trying to live their lives exist in both. Land and natural environment exist in both and usually override everything else in particular circumstances.

They also diverge. Things feel much more present and readily-at-hand in New Spain. The imperial force and the imperial power go together more swiftly and with less mental separation between them, at least in comparison to that of British America. There’s no doubt that spirituality takes opposite paths to a large degree, too—a more unified Catholic hierarchy and theology activates in New Spain, while a jumbled, uneven, and semi-raucous religious life defines British America.

Continuity and change, similarity and difference.

Suggestion

Take a moment and consider this—do parallels in separation still have a relationship to each other? And do the British and Spanish worlds of 250 years ago today underscore your point?

(waters in parallel)