Americanism Redux

January 25, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

Slumped against the front door, he’s reaching for the handle. With a few fingers on one hand, he grabs, holds, and turns. The door opens. The mob yells and shouts and taunts as he drags himself inside. He’s half-crawling, half-sliding on the wooden floor. The pain is now his entire life, pressing down hard, a weight over all of himself. Blinding and searing. In darkness he still hears mob sounds outside. A thought rises up in his mind, dancing and shimmering at a far place:

I need a box for my skin.

* * * * * * *

It’s today, 250 years ago, and in Boston, colony of Massachusetts, John Malcolm has struggled inside his home after this day of days. He’s been fighting with a boy, having slapped him and snarled at him. He’s been in a brawl with George Hewes, one of the pro-colonial rights, Native-dressed, last-resort tea-dumpers and a boy-sized man who came to the defense of the lad assaulted by Malcolm. That was earlier in the day.

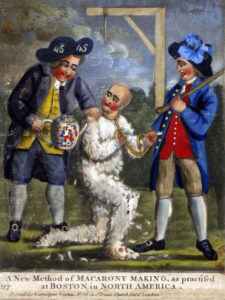

(a depiction, from 1774)

Since then, a large crowd assembled and surrounded Malcolm. Much of the crowd, perhaps nearly all, hadn’t been among the careful Native disguisers on the tea ships. And they weren’t interested in tea protests, either, choosing to bring with them an iron pot filled with pine tar. They started a roaring fire, set the pot on the flames, and waited. In a few minutes they dragged Malcolm into the street from his temporary lodging. They seized and punched him, fastened him down, and poured the steaming froth over his body. He screamed and writhed as the hot liquid sank into his skin. Some people in the crowd brought forth arm loads of goose feathers and scattered them over him. His red and swollen eyes streamed with tears; his mouth shouted without words. They grabbed him, untied him, and began pounding him senseless with plank boards and wooden staffs. Then, finally but not lastly, they hauled him from place to place to beat him further, holding him aloft for Bostonians to see, to jeer, and to witness. As they drove him along and repeated the stop-and-beatings, in the freezing cold, Malcolm wavered between total agony and lost consciousness. They had ended today with a tea-like dumping at the doorstep of his shelter. The mob flakes off, person by person. Here and there, you can see a few feathers that will soon blow away.

Malcolm now lays flat on the floor inside, gasping, aching, his frozen skin peeling away in strips. He thinks that he’ll need to keep the skin as evidence for imperial officials to see in the investigation, trial, and punishment that will surely occur. He’ll keep his skin protected in a box.

In the focus of thought, the human mind fascinates under duress.

* * * * * * *

Today, as John Malcolm suffers in Boston, the New York colonial Assembly has decided in New York City that it’s time to take up the request of other colonial legislatures and form a “Committee of Correspondence.” Unlike other colonial assemblies, however, the New York CofC is dominated by elected officials firmly supportive of imperial rights. The Assembly’s Speaker, John Cruger Jr, is a CofC member and he brings a wealth of imperially-oriented political and business experience to the group. The extended Cruger family has deep ties to England and, with others on the CofC, wants to shift the momentum of colonial protests away from such groups as New York’s self-titled “Mohawks” who had threatened violence a few weeks earlier.

(John Cruger, Jr)

* * * * * * *

22-year old James Madison reads today, 250 years ago. His reading material is law, legal, all things judicial. He works hard today like he does every day—studying, researching, writing, analyzing. He’s been thinking these past few days about the tea protests in Boston and Philadelphia, having learned about them from newspaper clippings sent to him by a close friend. To Madison, Boston’s protesters showed “boldness” while Philadelphia’s protesters showed “discretion.” He interprets last month’s contrasting protests as opportunities in political and military affairs to practice “the Art of defending Liberty and property.”

(James Madison, recent Princeton graduate)

Madison sees a complex link between these defenses and religion. He’s grateful that the British Empire in America has not imposed on colonial communities the Anglican Church, an affiliate of the Church of England, as the official form of Christian worship. To have done so, Madison reasons, would have meant the subtle spread of obedience, compliance, and passivity. To have a multitude of different worshippers, to have varied forms of Christian beliefs, he perceives, is to encourage individual growth, healthy debate, and a more fulfilling life as neighboring people.

Madison worries that six Baptist preachers currently in jail in the colony of Virginia, imprisoned for organizing non-Anglican religious services, indicate a dangerous trend. He knows from having read David Hume’s writings a couple of years ago as a Princeton College undergrad that monarchs become tyrants through such methods. He heard it in class, and from the college president, too.

* * * * * * *

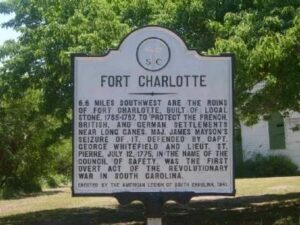

A British colonist living at the outpost, Augusta, colony of Georgia, writes today, 250 years ago: “from Fort Charlotte (near the Long Canes along South Carolina-Georgia border) Captain Taylor, of Colonel Savage’s Regiment of Militia, was to set out, on this Day, with a Party of Volunteers, to destroy the Indian Settlements on the Oconee and Ocmulgee Rivers; a Measure which many wish may not be attempted, as they are apprehensive it will be attended with fatal Consequences.”

(Fort Charlotte marker)

In other words, don’t do it, don’t go. Do something else and use another way.

Today, 250 years ago, a war burns between a coalition of Coweta and Creek Native tribes and British colonial settlements. There are attacks and counter-attacks, ambushes, raids, hit-and-run violence with one or two or ten wounded or killed at a time. Smoke hangs above cabins and villages. Taylor’s expedition is merely the latest.

You’ll see British imperial and British colonial military forces in the woods and swamps of the southern interior. Redcoated soldiers—the semi-conscious John Malcolm was a veteran Redcoat officer—in a professional job. Leather-shirted and woolen-shirted dwellers in a part-time necessity. Bloodshed. Warfare. Enemies. A dozen reasons and motivations.

Here the two pieces of British Empire often seek to join together. Will they become and remain one, like the Oconee and Ocmulgee that disappear into a single river, the Altahama? From these birth waters a path is found to the ocean.

But Taylor’s volunteers are heading the opposite direction. Up river, where it’s rumored the white traders are all dead.

* * * * * * *

Malcom’s torture. Cruger’s group. Madison’s thoughts. Taylor’s mission.

A single day reveals cross-currents in the American life of the British Empire.

Also

Today, 250 years ago, among the scores of ships arriving in British ports, a pair stands out.

One is the Hayley, owned by John Hancock of Boston, Massachusetts. The other is the Polly, Captain Samuel Ayres, of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

To paraphrase James Madison, the Hayley brings the first report of Boston’s “boldness-based” tea protest, and the Polly brings the first report of Philadelphia’s “discretion-based” tea protest.

British King George III’s immediate reaction: “I am much hurt that the instigation of bad men hath again drawn people of Boston to take such unjustifiable steps; but I trust by degrees tea will find its way to America.”

(George III)

* * * * * * *

John Pownall is wired-in. He holds two imperial offices in the monarchy of George III. He’s the Secretary of the Board of Trade as well as Under-Secretary of State at the American Department. He’s often in the presence of the king.

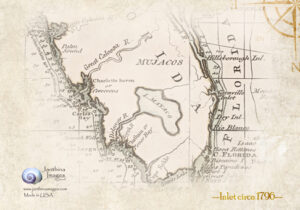

Today, in the name of the king Pownall notifies British Naval Captain Joseph Speer that he will receive an “honorary gold medal” for his recently drawn map of the West Indies. Speer’s map is a major improvement in the British imperial government’s knowledge of the Caribbean Sea and environs. Copies will be made and distributed to selected naval officers. Pownall will see to it.

(close-up of Speer’s map–note the level of detail)

* * * * * * *

Today 250 years ago is the third day of imperial rule by Abdul Hamid, Emperor of the Ottoman Empire. He’s in Constantinople (in modern Turkey).

He knows two problems stare him in the face. The first is that the imperial treasury is nearly empty. Funds gone. Hamid starts to consider taking drastic steps to cut spending—he’s mulling the possibility of stopping special annual payments to an elite group of soldiers known as the Janissaries. It’s a ticklish situation because they function as the emperor’s private guardians. If they become angry, anything can happen.

The other thing with which Hamid has to contend is the poor quality of the overall military itself. They’re proving unequal to the challenge of defeating the Russians in an ongoing war. Hamid will have to find a way to reform the military, which will almost certainly cost money.

No money for some soldiers here. New money to improve more soldiers there.

How ironic for a self-defined pacifist to have to grapple with the problems of war and war-making.

(Abdul Hamid I)

* * * * * * *

And today, standing on the deck of his ship Santiago, a man watches the settlement of San Blas, on the western coast of Mexico, disappear in the distance. He is Juan Josef Perez Hernandez and he’s on assignment. His task is to take the eighty-eight people on his ship, which is also packed with goods and animals, far up the Pacific coast of North America. He is to search for any evidence of Siberian incursions into the region, a place never before seen by any representative of the Spanish Empire. Until now or, to be precise, until the ship that is sailing now reaches its destination in the region of the Bering Sea.

(San Blas, looking toward the Pacific Ocean)

* * * * * * *

On this day, 250 years ago, the people of empires touch continents across the globe.

For You Now

The knife came out in Boston.

We’ve seen tensions spill into forcefulness. So far, and insofar as is known, the scene with Malcolm is the only one up to now that went to this extreme. If you’re living in Boston 250 years ago today you’ll likely wonder if something bad has started. Something may have crawled out from beneath the rock.

Keep in your own mind that Madison’s thoughts occur before he has any knowledge of Malcolm. Madison reacts as he does because he’s read history. He knows examples of what’s happened before when the darkness came. He’d remind you and me that often the light leaves when tyranny reigns. And he’d point you to other books that he’s reading, the law books.

The law is the light so long as liberty is the flame.

I find it beyond fascinating that Madison includes the life of the spiritual in his thinking. He’s gauging its condition, too. He’s measuring how it helps or hurts the light, how it keeps or snuffs the flame.

My guess is that Madison and the six Baptist preachers might not have a lot in common. I could be wrong. Whether I am or not, though, my point is that he cares about the substance and the symbol of their work and the impact on his community. He knows because he reads…and he thinks.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: What might worry Madison today?

(Your River)