Americanism Redux

February 8, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

You need to see this thing. Good God, it’s a massive tree. Down it came, crash and thud. By now, today, 250 years ago, the leaves are dead, the bark and branches gone, and the wood becomes plank and log. Other trees are laying next to it.

(Harrod’s tool)

Over there, that’s where the tree-chopper had stood only a few weeks ago, right over there, beads of sweat on his forehead, ax in his hand, snow on the ground. He’s James Harrod and you’ll see him somewhere around here among the tents used by the fifty of us sent by Dunmore, royal governor of the Virginia colony, to take this land. Thirsty? Walk over to the year-round bubbling spring, Big Spring, the Natives call it. Why bother changing the name that fits so well inside Kain-tuck-ee? Don’t worry, I’ll walk with you and make the introductions to Colonel Harrod.

If it’s a couple decades into the future, you’re about a two- day hike from a place where Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Hanks will marry, before they conceive the baby Abraham. For now, though, in early February 1774, Thomas’s parents—for whom their grandson Abraham will be named—are back in the colony of Virginia and Thomas himself is unborn.

So Harrod’s men work, the stump becomes a silent monument of the great tree, and two generations of Lincolns are yet to be born.

* * * * * * *

Reverend Eleazer Wheelock considers a future hundreds of miles away from hills and ridges around Big Spring. He is east of the White Mountains, at the college he founded, Dartmouth, in the colony of New Hampshire. Wheelock rests, recovering from a long recent journey. Traveling tires him. A tired body can’t stop a worried mind, though, for indeed tiredness can magnify the troubles.

(Wheelock’s Dartmouth)

He’s sitting quietly in his lodgings at the college and fearing for his traveling preachers. They’re from Native tribes, recent converts to Christianity. He’s writing a letter to let them know he wants them to visit him at the college. They can “preach their way back,” he advises them in the letter but, to himself, he’s nervous about the reception they’ll encounter along the way. Those lands with Native and colonist living in fresh proximity can be scenes of sharp tensions and sudden violence. Every such place once had a Harrod, a gleaming ax, and a felled tree.

Wheelock will truly rest when he can see his preachers safe again.

* * * * * * *

Reverend Joseph Willard, like Eleazer Wheelock, serves as a Congregational Christian minister. He’s familiar with Wheelock’s Dartmouth College founded four years ago. Willard’s weekly sermon, which he wrote and spoke forty-eight hours before, would have pleased Wheelock for both its theology and uses in daily life. Willard shared with the congregation in Beverly, colony of Massachusetts, his thoughts on the Biblical scripture of John 1:12—”But as many as received him, to them gave he power to become the Sons of God, even to them that believe on his name.” Willard implored his listeners to remember that they become “Sons of God” through the sacrifices of Jesus Christ. They receive all “privileges” through Christ and so become “Kings and High Priests” in heaven. To absorb Willard’s sermon on this past Sunday is to hear over and over that the earthly authority resides far below, and inferior to, heavenly reign. God, through Christ, Willard declares, makes the ultimate life.

(Willard’s church)

The same unknown that affects Wheelock’s mind this week also affects Willard’s: how goes it for my followers? Are they safe in the faith we hold dear? Can I, the minister who served the Word to them, feel certain in their security as the next days unfold?

* * * * * * *

These Christian ministers and their tortured minds….how hard it can be.

Today, 250 years ago and forty-two miles southwest of Willard, Reverend Ebenezer Parkman sits in anguish next to his church in Westborough, colony of Massachusetts. Actually, it’s annual anguish, the anniversary when, he says, “This Day I remember the Wormwood and the Gall, when it pleased God to take away the Desire of my Eyes, by the stroke of Death.” He’s referring to his first wife and her death in 1736, after she’d whispered a secret he vowed never to divulge. Parkman had since remarried, had children, and developed a full and purposeful life with his Westborough congregation. But he never stopped marking the by-way of this spot on the calendar’s map, never failing to remind himself of the bond he felt between human existence and divine guidance.

(Ebenezer Parkman)

Parkman’s emotional observance of this day is, as he well knows, a Revelatory thing. It is not, though, the man that comes around but the day that does the revolving, where time advancement becomes time immemorial.

It’s the rings on Harrod’s tree.

* * * * * * *

Henry Welles is what Ebenezer Parkman might have been back when the wormwood and gall were unknown.

(an older Henry B. Welles)

From his bedroom in Poughkeepsie, colony of New York, Henry Welles is about to reach over and blow out the light of a candle next to his bed. But not quite yet. He turns and looks at the “profile” of his fiancee, Sally, her likeness captured and framed as a silhouette. He sighs at her sight. Love. Longing. Desire. Frustration. Impatience. He wants to feel her beside him. That day is soon. The perfect beginning of the perfect life. A life of marriage. After their day of wedding. Good night, my sweet.

And the darkness appears.

* * * * * * *

In the colony of Virginia, Francis Willis can’t abide thinking about the wedding he’ll be attending. He knows that when the bride and groom have exchanged their vows, someone—likely the male host—will call for the music to begin playing. Lips on the flutes and fingers on the violins will begin their work. Couples of elegantly dressed men and women will walk to the open floor and begin the waltzes, the reels, and God knows what other dances. Willis hates the thought of it: “I am too old to Dance, and very well know, when Old People act out of Character, by desiring to appear Young, Men of Sense justly despise them, and Young People laugh at them.” Willis had no hesitation in sharing his views yesterday with George Washington, host of the wedding and the likely candidate to bring forth the musicians.

(the music-makers Willis dreads)

The wedding at Mount Vernon of Martha Washington’s oldest son, by her first marriage, will be one of the premier events of the Tidewater’s winter. Willis dreads it.

* * * * * * *

Further north of the Tidewater, the region shaped and defined by the Chesapeake Bay, William Whetcroft has asked the printer of the Maryland Gazette to display a public notice in the newspaper. Whetcroft is an economic magician in Annapolis—an Irish immigrant who has amassed wealth through making items from gold and silver, invested in real estate, and opened a merchandising store with a startling array of goods.

(in Chesapeake waters)

He’s also purchased a boat and in the boat he has people, his latest stock of resources primed for resale: “a parcel of healthy indented servants, consisting of tailors, shoemakers, blacksmiths, butchers, and sundry farmers and laborers. He also has for sale a quantity of the best new feathers and a few kegs of pickled salmon.”

You can’t read the ad without realizing a wizard is at work.

* * * * * * *

In Trenton, New Jersey, Richard Smith picks up the quill pen and scribbles his name on the parchment paper. He’s in the legislative Assembly, colony of New Jersey, joining in the signing of the newest legislative resolution to “keep up and maintain a Correspondence and Communication with our Sister Colonies.” It’s the latest addition to the network of several “Committees of Correspondence” and a direct effect of the various tea protests in Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, and Charleston.

Smith has to decide what his signature truly means. Is it a signature of starting or ending? Is his name attached to a Cause, to a people, to a person? To the past or present or future? Is the scratching of these letters—strung together in an order to embody, represent, symbolize, and stylize who he is, when you think about it—any more or less fateful than actions of the stump-maker in Kentucky, the reflective preachers in New England, the wedding participants of New York and Virginia, or the economic illusionist of the Chesapeake?

* * * * * * *

They’re striving to get through this day and the six others that make this week.

Also

Today, 250 years ago, in London, England, decisions of empire stalk the halls of power.

(source of the name for Wheelock’s college)

The Earl of Dartmouth, Secretary of State for the American colonies, oversees internal fact-finding about the American tea protests. He has crafted a twenty-two item report on events leading up to the colonial protests. The report includes specific names of protest leaders, such as Samuel and John Adams, John Hancock, Thomas Young, James Warren (Mercy’s husband—see last week’s entry), William Molineaux, and more. Dartmouth sends the report to a pair of imperial legal experts, along with a pair of questions: do the actions represent “high treason” and, if so, what should be done? Dartmouth waits for their answers.

* * * * * * *

This effort contrasts with unsolicited publications sent by English citizens to Dartmouth. Among them are the writings of Thomas Crowley, an unconventional Quaker, who argues for American representation in Parliament’s House of Commons and House of Lords. Crowley is driven from his Quaker meetinghouse for his unorthodox views of the Quaker faith. His American opinions underscore his belief in radicalism.

(later view of the Quaker meetinghouse where Crowley was expelled)

* * * * * * *

George III also writes to Dartmouth: “all men seem now to feel that the fatal compliance in 1766 (repealing the Stamp Act after strong colonial and British protests)” was a mistake; the British monarch states that some Americans seek an independence that is “quite subversive of the obedience which a Colony owes to its Mother Country.” If only the past could be re-lived and undone.

(later view of George III)

* * * * * * *

An advisor of George III’s, the Earl of Suffolk, has been tracking recent events in the Pugachev uprising inside the Russian Empire of Catherine the Great. He is keeping George III informed of political and military decisions. Meanwhile, less known but equally pertinent, Solomon I the Great commands 2,000 soldiers in a surprise attack on 4,000 Ottoman troops in the Battle of Chkheri. Solomon has earned his nickname of “the Great” for his unwavering determination to pursue local rule in Imereti along the Rioni River south of Russia. He’s helped to unite Eastern Orthodox churches, promote peaceful farming, and abolish the slave trade upon which the Ottoman Empire relied for part of its economy. Some might say that, for a while, he’s the “founding father” or “father of his country.” Officials in the Ottoman Empire fear that Solomon I the Great is allied with Catherine the Great and the Russians.

(Solomon I the Great)

* * * * * * *

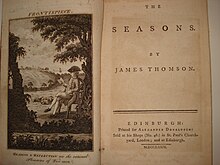

The House of Lords are hearing a legal case about who owns a public writing and if public writings can thus be suppressed by so-called owners. In “Donaldson v Beckett” a Scottish newspaper owner is claiming his right to publish a book of poetry—”The Seasons”—written by the deceased James Thomson. Alexander Donaldson had declared he could publish the work in his newspaper without fear of retribution from people asserting their own right of the material’s ownership. Donaldson’s arguments point to defense of a freer flow of news, information, and expression. Media observers across England and Scotland are watching the trial closely. The 21st century will see the case as a critical step in copyright law.

(the book behind Donaldson’s trial)

* * * * * * *

From an imperial view, power is to be closely held, widely used, and never shared.

For You Now

Safety and security in the living of daily life of the individual person and of the collective community. Who provides for it? From where is it provided? How is it done? And maybe before anything else should be asked and answered, what are their definitions?

We’re seeing a span of thoughts in today’s entry. Striving for change and the new, or in faith, love, wealth, or common cause.

Power will affect safety and security. Handled well, it can enhance and improve. Handled badly, it can be the worst threat and purest danger for safety and security.

So delicate it all is—with the desire seen everywhere and the ability found…

…anywhere?

(are these our images of safety and security?)

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: is safety and security high on your list of priorities? And how do you obtain them?

(your River)