Americanism Redux

February 23, on the path to the American Founding, 250 years ago today, in 1773

The pursuit of freedom can take you to weird places with odd relationships.

Today, 250 years ago, the pursuit of freedom leads to England, near London, where ship Captain Robert Calef sits in the home of a wealthy aristocratic woman named Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon. Calef has read aloud to the Countess. She swoons over Calef’s words: “is not this, or that, very fine? Do read another…!” And so Captain Calef reads on, in full voice, happily, excitedly, inwardly convinced that his prospects for success look increasingly good.

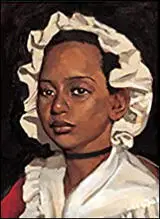

The poetic words reverberating in the room have been written by 20-year old Phillis Wheatley, an enslaved black woman in Boston. Calef captains the Wheatley family ship, fittingly called the London, and he’s here with the Countess to advocate for the publication of Phillis Wheatley’s poetry and essay writing. The Wheatleys—husband and wife—are certain that their enslaved Phillis’s writings should be widely known and admired, printed as a book. They couldn’t get it done in their hometown of Boston and now they’ve sent Calef asail to knock on influential doors and see what can be done for Phillis in Old England. As these early days of 1773 go by, the Wheatleys recognize the inevitable and the desirable: Phillis must be freed, and then all of humankind will benefit from her gift of creative writing. As for today, though, it seems the Countess may be inclined to pay for the publication of Phillis’s work in the more hospitable environment of Imperial London.

Read on, Captain, read on. Phillis’s future depends on it and today, with the reaction of the Countess, she’s one step closer to freedom in the form of a bound book.

(a depiction of Phillis Wheatley)

Today, 250 years ago, after Captain Robert Calef headed east to London to advocate for Phillis, Captain Zebulon Butler has gone west, the furthest west in fact you could go in organized British settlements. He’s on the western side of the Allegheny Mountains in the newest British county in North America. It’s Westmoreland and no British colonial community exists beyond here, except nearby Fort Pitt, which is a run-down military post and not a shining new settlement.

Butler steps back and admires the work of his new home, a log cabin for his wife, their three children, and himself. He’s cut the trees and hand-planed them into stackable logs. He’s filled crevices in the stacked walls with mud. He’s sawed openings for windows and a door. A fireplace of masoned stone anchors one end. On top of it all he’s slashed and slatted wood strips into rectangular tiles for his roof. His writing may not impress a Countess, but his handiwork here in the deep forests along the Wyoming River serves as art all its own.

Many of the people who’ve settled with Butler here in Westmoreland had lived near him in Connecticut. But in ways that did and didn’t resemble Phillis Wheatley in Boston, they sought a freedom not felt where they were. So, with Butler, they came west and declared their new home Westmoreland.

To them, name-choice carried weight. Westmoreland was also a county in the borderlands between Scotland, Ireland, and Imperial England. They brought from Westmoreland’s borderlands to Westmoreland’s Wyoming River their music—fiddles, mostly—their dances—reels and jigs, usually—and their words—”chaw” for chew and “young-uns” for young ones, typically. And after the playing and dancing and chatting they shared both a suspicion of outsiders and a willingness to use violence.

So, in a way, they’re doing what Phillis is doing. They’re arranging a freer life around a role of England. For her, England is a portal for a future. For them, England is a foundation for a future. Today, 250 years ago.

(current site where Zebulon Butler built his cabin)

Also

In England, at the same time Captain Calef is reading Phillis’s poetry to Countess Huntingdon, 47 year-old Charles Burney scans his latest manuscript before leaving it with a printer. During the past year he has traveled extensively across Europe, town to town, pen in hand, ears wide open. He’s been studying music in all its forms in various European nations. His book, forthcoming later this year of 1773, is “The Present State of Music in Germany, the Netherlands, and United Provinces.” Burney listens to music of a thousand makers, a thousand instruments, a thousand singers. He remarks upon the beauty or ugliness of towns and regions, the grace or brutishness of its residents and leaders. The skill of the young draw special attention from him, rather as Phillis has done in Boston and London; “little Mozart” is all the talk of Italy, writes Burney. He observes that parts of the German and Austrian countryside are too heavily forested, too dark and impenetrable, to allow for taste and refinement, the tracings of music. Had he ever traveled to the New World, one can almost predict an identical reaction from Burney upon encountering Westmoreland and Butler’s cabin.

(Charles Burney)

Another traveler and public commentator is thinking about writing today, 250 years ago. He is not a musician or musical theorist, but a farmer, and a transplanted farmer at that. It is rural New York, a week’s travel northeast from Zebulon Butler’s cabin in Westmoreland. J. Hector St. John Crevecouer is French, a former map-maker in the French military on the side opposing Zebulon Butler back in the 1750s, and now a citizen of British New York, Orange County, married to the daughter of a local merchant. He has discovered a love of farming. Deeper down, he’s discovered something else: his vision of a new world in America. He’s beginning to write about a style of life that is fresh and free, especially contrasting to his memory of France and Europe. He has an image in his mind of the writing he wants to do—showcasing the abundance of his adopted land, the gentleness of its manners, and the openness of paths to fulfillment and happiness. That’s the new world in his head, which he’ll begin to write up as a dialogue between a Catholic official and a fictitious character modeled after himself. His audience, he believes, will be European. He’ll realize, however, his market is not that distant.

(J. Hector St. John Crevecouer)

For You Now

Your individual quest runs through somewhere. The life you seek, and have sought, almost certainly involves the use of a place other than where you’ve ended up. Think of Phillis and Zebulon. That place may be from your past and you need to discard it. It also may be that you need to include it for the first time, because in your past you were unable to do so or unknowing of how to do so. Both of these statements apply to Phillis. Do they apply to you as well? For Zebulon, the prior time in his life is a source of steadiness in making a new home for himself and his family. Even though the homeland of his grandparents differs from that of his parents or him, that far-removed place still has resonance in seeing the new world around him. He moves west so he can restart, and return to, their home.

Then there are the people who attempt to make a higher point from their reflections and observations. They want to offer you some particular insight, based on their experiences. Burney and Crevecouer fit that mold perfectly. They believe you won’t know and thus will gain from having them inform you, to fill the void in your knowledge. But when they speak, or write, they’ll be doing so in order to fill their own voids of knowledge, too. How much they recognize their own gaps will go a long way in how valuable their thoughts are to you.

Phillis. Zebulon. Charles. Hector. Some seek freedom. Some judge if freedom—and its expression in music or farming—can be found. Today, 250 years ago.

Suggestion

Pinpoint a place through which you think freedom can be found.

(where’s the place through which it runs?)