Americanism Redux

February 22, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

“My life is (or is not) my own.” Which is it for you? Is the answer one of choice or of compulsion, your freedom or something else’s force? A blend of betweens?

Think about your day and week up to now. As you begin to separate time into pieces, do you see any hint of things you’re doing that are because some part of your life isn’t your own?

My life___my own. Fill in the blank: is/is not.

Today, 250 years ago, the ground shakes with answers.

* * * * * * *

(shaking)

A 30-year old woman runs terrified from an elegant home of brick and white-painted wood, designed to sit atop a small mountain. It happened yesterday and again today, 250 years ago. In either instance and in the two instances together, she can’t understand it; her mind flashes with images. To her, whole world is on the verge of upheaval, with the potential of angry gaps in the ground that swallow her, whale-like, to an unending death. Her nickname is “Bet”, short for Elizabeth, and she can’t seem to understand what other people see and know, even those who have run outside as she’s just done. Bet knows this: trust Little Sall. I want her to run with me so I can stop the terror while waves of land rise and fall.

Elizabeth Jefferson is sister to and one year younger than her brother Thomas. Brother has assigned an enslaved black woman to care for Sister who, the extended Jefferson family insists, has mental spasms and can’t cope with the day-to-day. With Little Sall’s help, Bet clings to as much of her life as she can.

Over the past forty-eight hours, an earthquake has shook the plantation home Monticello—Italian for “little mountain”—and the surrounding regions. In a matter of seconds, something invisible, beneath the crust, owns people’s lives and can bend them to its will.

* * * * * * *

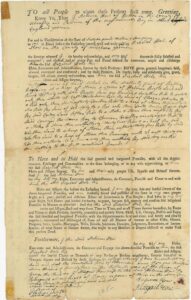

(the paper)

Unlike Jefferson’s little mountain in the colony of Virginia, the land is fixed, steady, and unquaking today in New Brittain township, colony of New Hampshire. Meseach Ware has just purchased a parcel of acreage. He handed over thirty-nine shillings to Benjamin Leavitt in front of two witnesses. On the deed is a description of the transaction, thick with detail. If anyone wants to bother to look, there is equally detailed wording on a survey account of the eighty acres, down to the physical markers of a tree, a rock, a creek, a measurable distance or other tangible facts that distinguish English and British conceptions of land as an ownable commodity.

These pieces of paper with written letters and numbers on them mean so much to the Europeans and their descendants. The papers—and the possessions they include—have been their way since ancient times, since before the earth shook, it seems. Such ways make things their own in the lives of the people who know them. Own the paper, own the land, own the life.

Meseach Ware holds his paper. But not everyone will understand.

* * * * * * *

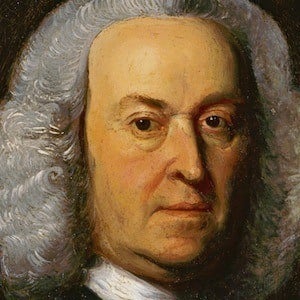

(when he was healthy)

Should I leave him? Should I follow my instinct and my plan to go to England and find the safety my family and I deserve? Look at him, frail, thin, coughing, weakening. Dying? I can’t tell but I know this: I’m not leaving Boston until I know what his fate will be.

These thoughts fire the mind of British Governor Thomas Hutchinson, colony of Massachusetts, looking at his friend, Lieutenant Governor Andrew Oliver, on his sick bed and, perhaps, on his death bed. Peter Oliver, Andrew’s brother, had been impeached only a week ago by tea-dumping-protestors serving in the colony’s legislature. The Olivers are a reason Hutchinson senses everything is spinning out of control. He’s judged that he can’t be effective any longer as governor. And he’s also certain that protestors have no idea about goals or plans and simply want no laws, no morals, no trade, no religion. All they want, Hutchinson fears and believes that he knows, is to destroy.

He stares. The man in the bed, wasting away. The expensive clock on the wall, ticking away. The sea water against the ship set to transport him, lapping away. Fish have long since watched particles of tea leaves sinking to the harbor’s floor, where they became deeded to the bottom-dwellers.

Up on the surface, safety is a disappearing fact in the ownership of life.

* * * * * * *

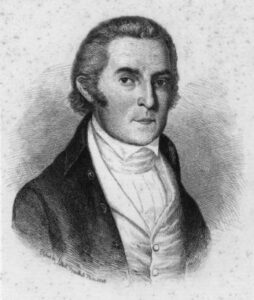

(James Iredell)

None of this is known to 22-year old James Iredell and that’s certainly for the best. It’s his first week on the job as a British imperial customs collector, port of Edenton, colony of North Carolina, a position he’s wanted as a loyal Englishman, born in the mother country. He’s also well-known and well-liked in his adopted home of Edenton, so much so that he’s a self-described colonial Carolinian, too. He’s a young man of many homes wearing one new hat of appointed imperial official in, of all things, enforcement of things like the Tea Act.

Understandably, and even without the immediate knowledge of Hutchinson’s agony in Boston, Iredell is extremely nervous. He is already among the most insightful and intelligent legal minds in the British colonies. And that means he carries the burden of seeing more than one side to a problem—he perceives both the pro-imperial argument for order and obedience and the anti-imperial argument for freedom and rights. He not only understands the two sides, he feels at home in each side.

Which will claim ownership of his life? One heart, two homes.

* * * * * * *

(hidden flames)

Seventeen young men in the woods of the southern Appalachian Mountains surround a campfire. They’ve kept it hidden, the smoke barely seen. They are on a quest to destroy the safety of those they can reach, to kill and claim the lives of victims. These young men move quietly from place to place, camp to camp, with shelters concealed in vines and tree branches. They’re watching for a chance—a chance to find an isolated person, or maybe three or four, and unleash a surprise attack. Whatever the dead have the attackers will take. The entire experience binds the seventeen young men together, the movements, the actions, the purpose of plunder and vengeance against Natives like themselves, or whites wearing leather shirts, red uniforms, or simple dyed clothing of man or woman or child. These seventeen are, according to a British Redcoat officer, “a straggling Banditti, who have separated themselves from the (Creek tribal) nation and by that means are not subject to any authority.”

Streaking into the galaxy of political order, seventeen people form a comet to make war of their waging, operating at the most sub-particle level of life with other people. Owning comes from collision where the strong live and the weak die.

* * * * * * *

(the German reciters of rights)

The disorder of elemental life sought by the seventeen war-makers strikes at part of what George Washington perceives in people along the Rhine River valley in central Europe. He continues with his plans to entice the German “Palatinates” to his land—with all the deeds and documents to prove his ownership—in the Ohio River valley. He thinks that at the basis of their way of living is this: “I see no prospects of these people being restrained in the smallest degree, either in their civil or religious privileges; which I take notice of, because those are privileges, which mankind are solicitous to enjoy, and emigrants must be conscious to know.”

To own one’s life is to live according to core rights, or privileges, this is the attitude of Mount Vernon’s owner in the colony of Virginia. The living own the rights of life.

* * * * * * *

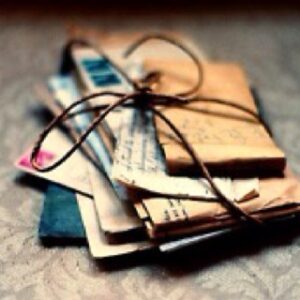

(like Joe’s bundle)

Joe is on his way today to find Mr. Washington. An enslaved man, Joe is traveling from Prince George’s County, colony of Maryland, to Annapolis, about twenty-five miles in distance. He’s carrying a bundle of letters for Washington to read. Joe has done this sort of thing before, delivering letters from writer to recipient, intact and unopened. And Joe starts out his journey from nearby an area that will one day be called Washington DC.

Somewhere in Joe’s bundle of letters is an invisible quantity of trust and recognition of reliability. Do the trust and reliability also convey the existence of respect? It’s hard to know. Does freedom also reside somewhere in the bundle? It’s hard to say. Only a test will reveal the truth.

On the road to Annapolis, a life survives with liberty denied, going round and round like a turning wheel.

* * * * * * *

(in O’Sheal’s county of Chester)

Today, Charles O’Sheal was supposed to make a final payment for his liberty. He doesn’t have the money. He is an indentured servant in Chester County, colony of Pennsylvania, under fixed contract to Florence Schranlen. The contract obligated for him to sell himself to her for a period of years in exchange for learning a skill. She owns a small plot of land and, until he comes up with his final “freedom payment”, she will continue to own his labor, too. O’Sheal wonders where he can scrape up the liberty funds. He’s got three months to get them together.

Sometimes it’s not easy to settle on exactly one of life’s owners. There can be too many to count.

* * * * * * *

(where a legend lived in Surry County)

As O’Sheal looks at the tyranny of his empty pockets, they’re reading the will of a deceased legend in the courthouse of Surry County, colony of Virginia, where the gravestones shook from an earthquake. The departed is Elizabeth Bray Allen Smith Stith. The legend isn’t because she outlived three husbands, though it built mystique, without question. More than that, however, her stellar reputation comes from the fact that she had founded and operated a school for impoverished boys and girls. They give her two years of their effort and she gives them two years of learning to read, write, and master other applied subjects and—AND—if they finish the obligated terms, they are placed in an apprenticeship or work position where they can start earning a living. It’s the stuff of local educational and occupational heroism.

Oh, and in her will, she left money specifically for the education of her grandchildren.

The EBASS way: a now-term effort acquires near-term knowledge creating long-term gain. Give up some to get a lot more, walking a path toward life-owning.

* * * * * * *

(Mamma’s Boy as a young man, John)

To his “Mamma’s” second husband, the step-son wrote this about the contributions of the older man: I know that all you have done for me “proceeded from a Generous & disinterested Mind, and that the only returns required, were Affection and regard—both of which did I not possess in the highest Degree for You; I should look upon myself to be the most insensible & Ungrateful Being on Earth; and shall strenuously endeavor by my future Conduct, to merit a Continuance of your regard and Esteem.”

Somewhere the border runs between the life you think you own and the life others have helped you own. Few young people are as aware of it, today 250 years ago, as John Parke Custis, newly married to Nelle and step-son of George Washington, second husband of “Mamma” Martha.

Also

(point of departure for the two families)

“Let me know when you see Captain Combes.”

Today, 250 years ago, in London, England, two sets of immigrants are saying the thing. William Combes is captain of the ship “Union” and he’s bound for the colonies in America, Charleston in the colony of South Carolina, to be precise.

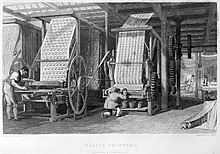

One group keeping close watch of Combes is the Ogier family. Two parents in their early 40s, eight children spanning age 20 down to age 5. They are Christians from France, recently relocated to England. Most of the Ogiers are weavers or in the weaving trade, including the teenagers. The industry is in the midst of wrenching changes coming at people a thousand-miles-an-hour. So the Ogiers are off, or will be soon, seeking a new life in Carolina.

The other group is smaller in size, a husband and wife, John and Mary Macklin, born and raised English. The Macklins are perfumers, specialists in the making, buying, and selling of perfumes. They relish their access to the wealthier people of English society, pegging a livelihood to servicing the luxurious enjoyment of perfumes. But they’re a bit bored with life and want to see what a reset in the colonies will bring them. Carolina is Combes’s destination? Seems fine to us. Send word when the captain is ready to set sail.

* * * * * * *

(the new industry)

Today, Parliament votes to repeal the Calico Act. It was a fifty-year old law that had protected the British East India Company’s production of woven cloth. No more. Other England-based weaving businesses are now relocating next to streams and rivers so they can power weaving devices clustered under one factory’s roof. The Act is out of date. The Act is now off the books. Get busy weavers, time is money and the world is the market.

* * * * * * *

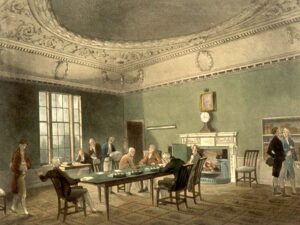

(the Board of Trade at work)

The four-man Board of Trade has sent a pair of names—Willie Jones and Thomas McGwire—to King George III for his consideration as the two newest members of the governor’s high council in the colony of North Carolina. After the monarch’s expected approval, Jones and McGwire will soon meet young James Iredell as part of “team king” in the colony.

* * * * * * *

(fox on the run)

Benjamin Franklin is assailed from all sides today 250 years ago. Still in London, he’s writing letters under his own name to end friendships with a positive tone; they resent him for having leaked the private letters months ago. He’s also writing fake newspaper reports that defend himself publicly in the third-person. He’s further writing his son William—whom he fathered out of wedlock—to advise him how to deal with the fallout from Benjamin’s recent humiliation in a Parliamentary hearing and his subsequent public firing as colonial postmaster-general. Intellectual partners and compatriots like David Hume are rethinking their view of Franklin. The world’s best known American colonist is hunted by the hounds, a feeling that one of writers of the leaked letters, Thomas Hutchinson, ironically knows all too well back in Boston, bedside by the stricken Oliver.

* * * * * * *

The King’s Privy Council will now hear testimony from Hugh Williamson, late of the American colonies…

He gets straight to the point. Continue the current British course of colonial policy in America and the result will be ruin and disaster. Williamson predicts one of two outcomes: civil war or revolution. The Council’s members shift uneasily in their padded chairs.

For You Now

(seismic read-out)

Pause for a second and think about the difference between civil war and revolution. Big stuff. I spend a massive chunk of my mental life on this point.

Let’s combine two things now. One is your answer to my question at the top—my life is/is not my own. I’ll wager your response is fascinating. Too bad you and I can’t explore it together. Ah well. Regardless, get your response in your mind.

Next, bring in Williamson’s explosive statement to the Privy Council—civil war or revolution. In very real terms, Williamson is describing a potential human earthquake.

If that earthquake hits and the needle starts swinging, the answers to the “my life is” question for the people of 250 years ago will almost certainly be turned upside down.

Close your eyes and imagine them, Bet and Little Sall, holding on to each other, atop the leviathan underground.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: what is my answer to “my life is/is not my own?

(your River)