Americanism Redux

February 15, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

There is a day when you know the driver of your life. It’s the most basic, single element of your living. On this day you’re crystal-clear about your life-drivers.

* * * * * * *

Today, 250 years ago, a British ship enters the port of a colonial city. The ship carries important cargo. It is cause for great excitement, a stirring. Yes, that’s right, a ship from England, a colonial port, and public significance for daily life.

You can’t be serious. Here we go again?

This time the port is New York City, the ship is the “Virginia,” and the cargo is not tea, thank God. It’s copper, weighing five tons, specifically, 670,000 “half-pennies”. The coins are newly minted in England despite being requested a year ago by the legislature of the colony of Virginia, where the coins will now be sent. The coins are desperately needed hard currency in a colony where people have little faith in the face value of money for buying and selling. An economic transaction requires trust and the level of monetary trust in Virginia is hovering near-bottom.

(670,000 of these critters)

The problem is the shipment lacks one thing—formal authorization from the British imperial government for its use to begin. The minting was approved but the actual circulation of the coins was not yet granted. So, they wait. Hopefully, not too long. If normal stays normal, maybe the spring will bring word. Unless some other issue requires attention—an issue like, say, tea protests. No one can say for sure.

For many people in the colony of Virginia in need of these coins to use in transactions for food, shelter, and a hundred other things, the contents of the ship “Virginia” is a driver of life.

* * * * * * *

(a bachelor no longer, sort of)

General Frederick Haldimand sits today in his military quarters in New York City with his “companion”, Mrs. Henry Fairchild, a life-driver he found to his great surprise. Together they learn about the coin shipment. Haldimand is in temporary command of a small British Redcoat contingent in the port city. He’s enjoying his time with his new partner in life, her husband having vanished in the delta region of the Mississippi River with no questions asked. A bachelor, Haldimand relishes the thought of having someone he can trust to hear his complaints about the problems of his day, which, today, will be his nervousness of how local people will react to having the five tons of half-pennies in their midst. Companionship has softened the rougher edges of this soldier’s life.

* * * * * * *

A potential supplier to Haldimand’s military force is Aaron Lopez of Providence, colony of Rhode Island. Lopez is one of the biggest oil importers in the colonies, one of the wealthiest merchants, too, along with a reputation for philanthropy second to none. Today, he’s in Newport overseeing the unloading of sixty massive casks of whale oil from a docked ship. The oil will be sold for use as fuel for lamps, as material for making candles, as lubricants for printing presses and mill wheels and metal production. Lopez also has a sprawling fleet and network for the slave trade which he operates as a satisfied money-maker. Prized most in his daily world is stability, the steadiness of knowing routes are open, calculations for prices and costs can be done, and the pledge of buyer and seller can be trusted. All praise to Yahweh, thinks the Jewish Lopez.

(Aaron Lopez, 18th century oil man)

* * * * * * *

Lopez’s slave-trading ships may have brought Phillis to the New World as an enslaved girl, or it may have been another ship to have done so. Phillis Wheatley, the newly-freed black teenage girl remains a name on many lips in the colonies of Massachusetts and Rhode Island and across southern New England. Phillis’s poems and essays astound readers and listeners, with every word undercutting and overwhelming public assumptions about enslaved black people. And today, 250 years ago, Phillis writes a letter to Samson Occum that is stunning in its arc and depth and range.

(The Thinker, Phillis Wheatley-style)

“Those that invade them (the human rights of black people) cannot be insensible that the divine Light is chasing away the thick Darkness which broods over the Land of Africa; and the Chaos which has reigned so long, is converting into beautiful Order, and reveals more and more clearly, the glorious Dispensation of civil and religious Liberty, which are so inseparably Linked, that there is little or no Enjoyment of one Without the other: Otherwise, perhaps, the Israelites had been less solicitous for their Freedom from Egyptian slavery; I do not say they would have been contented without it, by no means, for in every human Breast, God has implanted a Principle, which we call Love of Freedom; it is impatient of Oppression, and pants for Deliverance; and by the Leave of our modern Egyptians I will assert, that the same Principle lives in us. God grant Deliverance in his own Way and Time, and get him honor upon all those whose Avarice impels them to countenance and help forward the Calamities of their fellow Creatures. This I desire not for their Hurt, but to convince them of the strange Absurdity of their Conduct whose Words and Actions so diametrically, opposite. I humbly think it does not require the Penetration of a Philosopher to determine.”

So writes the young African freed-woman to an older Native Christian evangelist and educator, on the drivers of her life, his life, all lives, on individual freedom and human rights across hearts, across hemispheres, across epochs.

* * * * * * *

Robert Adam is continent-wise, like Wheatley and Lopez, meaning he’s had deep experiences across more than one land mass. He’s writing a letter as well. In it he shares his unique knowledge, drawn from years as a Scottish-born trader now living in the colony of Virginia. Adam’s knowledge pertains to the impulses he’s observed in what makes some people up-end their lives, cross an ocean, and restart life in a new and strange place. Adam believes that inhabitants of the Rhine River valley in central Europe place great value on religious freedom. They will eagerly relocate to the colony of Pennsylvania, with its reputation for religious diversity. He predicts they will seldom move to the colonies of Virginia and Maryland because greater restrictions and prohibitions on religion exist there. Adam believes the people of Ireland and Scotland—especially those near-starvation and impoverishment—will be more likely to move to the Chesapeake colonies. They’ll be less worried about religion, Adam predicts. The stomach as well as the soul comprise Adam’s view of the basics of life.

(from the Rhine)

* * * * * * *

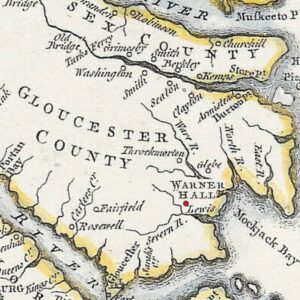

John Roots has given it eleven years. A decade plus one year is more than enough time, in his thinking of it. It’s been eleven years since he received 3000 acres in the Ohio River valley from the British Governor of the colony of Virginia in exchange for Roots’s military service during the French and Indian War. Whatever dream had floated in his head—maybe more of an illusion, actually—of going west and hacking out a life in defiance of disease, Native attacks, severe weather, and a dozen other threats, well, they’re gone now. He’s not up to the reality he’s been hearing about in the Ohio country: potential war between Virginia and Pennsylvania, settler and Native, Native and Native, British Empire and French Empire, the Saved and the Heathen, God-knows-who and God-knows-what. He’s selling out the acreage to a wealthy land investor and settling into a daily life that suits and secures him well enough, season to season, in Gloucester County, colony of Virginia. And now he has cash and credit on hand from the land sale, which he can spend in a small local town, across the York River, called Yorktown.

(Gloucester County)

It’s the place where, in three years shy of a decade, the British will surrender to the man who had bought Roots’s Ohio land—George Washington.

* * * * * * *

The interior regions of the colony of Georgia have, for a while at least, bid farewell to armed conflict. It’s not exactly peace, just no open violence for a period of a few days and, who knows, maybe longer. The Cherokee tribes have asserted their desire to stop fighting and have built twelve stockade-forts. The Creek tribes say the same thing, excepting their willingness to fight the Choctaw tribes further inland. The issue now in this awkwardly quiet moment is how to deal with “Mad Young Men” perhaps bent on making trouble and “the fugitives” too terrified to remake their lives. The driving forces of life at ground-zero in the far southern Appalachian Mountains feature an invisible line between an instinct to live versus an instinct not to die. The nightly frost feels like a final breath.

(Georgia’s southern Appalachian Mountains)

* * * * * * *

Today, 250 years ago, a frenzy spreads in the streets of Boston, colony of Massachusetts. For minutes stretching to hours the passions and thoughts of many people shift from the weeks-old tea-dumping to a sudden shock of news bursting now from the Statehouse. The colony’s legislature sits in session and has just voted to impeach the colony’s chief justice, Peter Oliver, one of the symbols of imperial power in this town of tensions.

(Chief Justice Peter Oliver)

The bomb-like explosion of news sweeps through the streets and into the taverns, the churches, the shops, the homes, the docks, the farms, and beyond. People talk in excited tones about Oliver’s impeachment. Of course, the British Governor Thomas Hutchinson will ignore the vote but no one cares. They got one, they bagged one, they nailed one to the wall. God be praised, Yahweh be praised, saints be praised, and anything else anyone can think of be praised, too. A British official wrapped in imperial trappings; Oliver is out! It must have felt this way when heaven hurled the lightning at Dr. Franklin’s kite. Life can be driven by pure electricity.

Also

Benjamin Franklin adjusts his eyeglass—the bifocals he invented—to improve his eyesight. 250 years ago today, he’s still in London, England, wrapping up the various loose ends of being fired from his position as postmaster-general of the British colonies in America. He’s keeping close watch on people and their comings-and-goings around Parliament. When he lands back in America, Franklin wants to be able to update his colonial contacts about what Parliament will do in response to the tea protests. He knows a list of names of protest leaders is being developed. He guesses that Parliament will do something specific in this legislative session. Beyond that, he can’t quite see, even with smudge-free eyeglasses.

(with clean glasses)

* * * * * * *

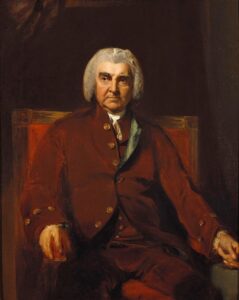

Like Franklin, fellow colonist Henry Laurens is also in London. He’s there with his son who is studying to be a lawyer. Henry Laurens has learned about the tea protests and is proud enough to pop the buttons on his expensive waistcoat for the careful and cautious approach of his native home, Charleston, colony of South Carolina. Laurens praises his home-town protesters for not destroying the tea. He thinks their protesting counterparts in Boston made a bad mistake in their tea-dumping. He tells a friend that the Bostonians should pay for the damages and sail a smoother course in upcoming weeks. That’s precisely what he knows his son-turning-lawyer is learning with his legal studies. Life’s drivers are emotions kept in check, passions held to reason, and change made in calm motions.

(Henry Laurens)

* * * * * * *

The law-learning Laurens hasn’t been taught yet about the reality of law behind closed doors. It would be an amazing tutorial for him today if he could have had the chance to hear Edward Thurlow and Alexander Wedderburn. The two imperial lawyers who work for the British king used to hate each other. Now, they’re best friends, or something like that, because the pair of them smell a bureaucratic agenda to have the Boston tea-dumpers pursued and prosecuted as a legal matter instead of a political and Parliamentary issue. The two lawyers are united in resisting the legal and judicial course: “who,” says Thurlow, “would be such damned fools as to risk themselves for such damned fellows as these (the tea protest leaders).” In other words: want to ruin your legal career in imperial government? Here’s a perfect way to do it—be the one in charge of unending legal prosecution of the colonial tea protesters three thousand miles away. The critics will chew your life’s work away and you’ll be left drifting without a life-driver.

(Edward Thurlow)

* * * * * * *

Lord North may save them from their griping. As prime minister in Parliament, he’s been busy completing his own private quest to know the true capabilities of the British Royal Navy, regarded as the world’s best. He learned the opinions of naval leaders and experts and has decided that, yes, the Royal Navy is up to the task of potentially blockading the port of Boston in retaliation for the tea-dumping. North’s own memory added to his conclusion; it was only a few months ago that he and King George III stood on shore and witnessed a line of Union-Jack-flying military vessels sailing by them in an official display. It was British military sea-power at its best. Yes, they can manage it quite well, thinks North, holding in his mind an array of power-cards in his hand. Power, played in the game around the empire table, is for him a life-driver.

(he’s a go with the Navy)

* * * * * * *

Almost eight weeks in the past for the colonial tea protests and not quite three weeks since the first news landed in England, the imperial response is starting to take a shadowy form. Protest leaders—on a list—action against them—involving a non-war use of military power. When finally ready, the response will contact people and their life-drivers.

For You Now

The access to food. The ingress to faith. The presence of money. The absence of war. These are among the life-drivers, the basics of living above survival for many people, including some in our entry above for the middle of 250 Februarys ago.

The clarity of which one or ones animate you can reflect the overall situation in the present. Tragedy, crisis, or difficulty can wipe away smudgy distractions. They clear off a space for you to account and assess more quickly than before. Seeing what’s left standing can allow you to stride ahead with great speed, regardless of uneven ground.

(moonscape as landscape)

Phillis Wheatley’s letter—the one where she consciously invokes “clear and clearly”—speaks of a movement that is gleaming in the distance. It is a movement of freedom and liberty, openly described and articulated not only for a coast and region but a continent and world as well. She notes in powerful tones, however, that the movement’s language and the movement’s actions do not align. As a woman of private actions and public words, she is suited to reveal the gap. Left alone, the gap could become a famished emptiness that feeds on the living and where, above ground, only survival is true.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: would you join a movement that reflected your life-drivers?

(Your River)