Americanism Redux

December 7, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1773

It feels like overnight. The change. Fast, everywhere. You look back a few weeks or months and it seems like a different world then. Not that world now. All at once, or so your heart and mind and soul tell you.

* * * * * * *

Today, 250 years ago, Francis Salvador steps off the ship docked in the harbor of Charleston, colony of South Carolina. He’s thinking about the world back there, on the other side of the Atlantic.

(Francis Salvador)

It had been a place of wealth and woe. As a Sephardic Jew, his ancestors had been driven from their Portugal homeland, pushed out by Catholic officials who had denounced Judaism and Jewish believers. Francis’s family resettled in England and Holland and earned astounding wealth from finance, shipping, and merchandising. So vast was the wealth that Francis received L60,000 from his family upon adulthood. At the same time, his uncle and father-in-law had purchased thousands of acres in the British colony of South Carolina with the intent of resettling family members and poorer Jews there. Since then, the family had lost most of its fortune through natural disasters like earthquakes and business disasters like the bankruptcy of the Dutch East India Company.

And so Francis stepped off the boat in Charleston.

He wasn’t a half-hour on land and a half-mile from the sea water when it hit him. It assaulted his senses—sight, sound, and maybe even smell, taste, and touch.

It was everything and it was everywhere.

* * * * * * *

What Francis Salvador encountered as he walked along the cobblestones of Charleston was the new world of protests, resistance, and opposition to the tea of the British East India Company. The British ship London had 257 chests of tea aboard and just four days ago a shocking display of colonial rights had exploded in the middle of Charleston.

(The Exchange, in Charleston)

On December 3, an event now ninety-six hours old, had unfolded. Action—bold, direct, and forceful action—had taken place. On that day, people began pointing and shouting: it’s here, it’s here, the ship with the tea is here! Hundreds of local people in Charleston had rushed into the streets. Among them were the members of “Club 45” that less than two weeks ago had held an unforgettable public march, fireworks, and celebration of anti-tea fervor and unapologetic declarations of colonial rights. The hours-long event had laid the groundwork for December 3’s outpouring of people at the sight of the tea-laden ship, London.

Members of Club 45 had directed the crowds of December 3 into the “Great Hall” of a building called “The Exchange”, a well-known structure in the town. Along with the crowd, some participants from Club 45 had grabbed three men who were known to be designated as tea distributers, or tea consignees. Together, the crowd and the frightened trio of tea officials, they crammed into the Great Hall “to take the sense of the people so collected,” as one observer put it, “(about) what could be the absolutely necessary to be done in the present case.”

Christopher Gadsden of Club 45 dominated the scene. Without any notes in front of him, he delivered a ferocious speech. He demanded the three tea distributors sign an agreement “not to import any more teas that could pay duties, laid for the UNCONSTITUTIONAL purpose of raising a revenue from us, WITHOUT OUR CONSENT!!” The crowd roared in agreement. Terrified, the three men complied, their signatures written with trembling hands. The tea stayed on the ship. The ship stayed in the harbor. The scene since then had remained under the power exerted by Club 45 and Charleston’s colonial rights supporters. It’s the first act of forceful, aggressive, and open-ended defiance against the British imperial government and its tea-flavored laws enacted seven months ago. The colony’s royal governor, William Bull, might as well not even exist.

Scarcely an hour in Charleston, Francis Salvador knows which side he’s on. Point him to The Exchange so he can soak up the ambiance of freedom, liberty, and the happiness he’s set to pursue. Point him to the people to whom he can talk about his role in the onrushing cause.

* * * * * * *

In Philadelphia, a day after Charleston’s trio of tea distributors resigned in the Great Hall, opponents of the shipped EIC tea are worried. The focus of their worry isn’t in England. It’s in Boston. They’re not entirely sure that Boston’s anti-tea leaders, such as Samuel Adams, John Hancock, and others, are up to the challenge of resistance, especially if an economic boycott of British goods is the next step of resistance. Philadelphia’s anti-tea leaders express their worries about the Boston group publicly, in a newspaper: “May God give (the Bostonians) Virtue enough to move the Liberties of your Country, and depend on it, is shall not be betray them here.”

(Dr. Benjamin Rush, a colonial rights leader in Philadelphia)

The colonial rights movement isn’t so simple as a singular mass after all, but rather a collection of smaller movements groping toward collaboration, stumbling toward common ground. Nothing is guaranteed.

* * * * * * *

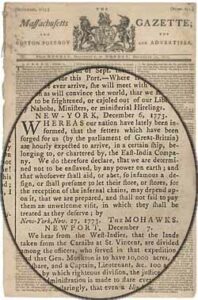

Incredibly, a new image enters the moment, today 250 years ago. From New York City, aimed at Boston, but perhaps with integration from people in both places, a startling public announcement appears to readers in these two largest communities north of Philadelphia.

A public declaration written in New York City and targeted for a Boston audience reads as follows: “We do therefore declare, that we are determined not to be enslaved by any power on earth; and that whosoever shall aid, or abet, so infamous a design…may depend upon it, that we are prepared, and shall not fail to pay them an unwelcome visit, in which they shall be treated as they deserve by The Mohawks.”

The Mohawks were a widely known Native tribe within the confederation called “Six Nations” by the British. Living in central, western, and northern New York colony, the Mohawks were legendary among British colonists for political prowess, skill in war, and diplomatic acumen. Books, art, songs, and language used by British colonists invoked Mohawks. To self-designate as “Mohawk” by colonial rights leaders was as clear in symbolic meaning as an arrow or tomahawk. Some leaders were laying claim to a uniquely North American symbol to express a strikingly American identity.

The tea on the ships was unleashing more than a protest.

* * * * * * *

In the middle of Boston harbor, not far from the three British ships laden with tea and stalemated in their future plans, is Lt. Col. Alexander Leslie, an officer with the 64th Regiment of Foot, a unit of British Redcoats. Leslie sits in his quarters at Castle William, the same place where the Clarkes, in-laws of painter John Singleton Copley, stay temporarily for their safety as tea consignee Richard Clarke decides the next move for he and his family. Leslie has certainly seen the Clarkes since their unexpected arrival as, in reality, local political refugees.

(Alexander Leslie, after promotion to General)

Lt. Col. Leslie writes a letter to the British Secretary of War, Viscount Lord Barrington, about a dozen pay-grades above the Redcoat officer in rank, power, and influence. Leslie describes for Barrington the conditions in Boston—tensions on the knife’s edge, mutual hostility between pro-imperial and pro-colonial rights groups, the ships with unloaded tea anchored in the harbor. Leslie also shares analysis of his own: it was a mistake of Governor Thomas Hutchinson not to call upon Leslie’s 64th for help after the “volunteer guards” of the protestors had emerged from the crowds to stand watch over the ships from the docks. Leslie believes an alternative path could have been followed—the two groups of armed men, one professional and the other ragtag, would have squared off with the result being tea unloaded into its rightful place on land. Instead, laments Leslie, the harbor is the arena for a standoff.

The officer stares at his finished letter. The ink of his letters and words has absorbed into the parchment. The quill is at rest. The light flickers from a nearby candle, shadows dancing on the desk. Tomorrow, another day of duty awaits Leslie.

The Clarkes will never know about Leslie’s analysis.

If only. If only.

* * * * * * *

South of Castle William, south of Boston harbor and the three motionless ships, south of Old South Meeting House where the recent crowds had gathered and decided what to declare, Abigail Adams is finally herself again in Braintree, colony of Massachusetts. A fever had almost killed her over the past few weeks. Thankfully, she knows she getting healthy at last.

The joy inside her competes with sadness and contemplation of trouble ahead. Not like the usual things, this trouble is bigger.

(Abigail Adams, feverless)

Abigail finds the words: “Tea that bainful weed is arrived…The proceedings of our Citizens has been United, Spirited, and firm. The flame is kindled and like Lightning it catches from Soul to Soul. Great will be the devastation if not timely quenched or allayed by some more Lenient Measures. Altho the mind is shocked at the Thought of shedding Humane Blood, more Especially the Blood of our Countrymen, and a civil War is of all Wars, the most dreadful, Such is the present Spirit that Prevails….”

She continues to search her mind for the thoughts that best explain her outlook.

“If they are once made desperate Many, very Many of our Heroes, will spend their lives in the cause, With the Speech of Cato in their Mouths, ‘What a pity it is, that we can die but once to save our Country.'”

Abigail feels her brow. Cool to the touch of her fingers. Yes, the fever is gone. Fully alive, she’s wondering about the wish of dying multiple deaths.

Also

The play “Cato” is in its sixtieth year by the time that Abigail Adams remembers one of the play’s most famous quotes. The playwright was Joseph Addison, who died not long after the play’s premiere in 1713.

(Joseph Addison)

When he was a young boy, the future British king, George III, would have a small and especially constructed role in a stage production of “Cato”.

Today, 250 years ago in 1773, Addison’s poetic works have been republished and reissued in London, England. The book has skyrocketed to popularity in the British colonies, read and often memorized by Abigail Adams and hundreds of other British colonists. The young school teacher Nathan Hale will be among its devoted readers. Participants in the resistance to the Tea and Governing Acts flip the book’s pages to find passages to instruct, words to inspire.

The play depicts the story of Cato The Younger and his resistance to the tyranny of Julius Caesar. Cato displays unwavering virtue in opposition to the emperor, a position he takes during a horrific civil war. He commits suicide for his stance, a death fated by honor, duty, and nobility. His quote about the loss of a single life is set against this backdrop.

Which changes more: the meaning of words over the years or the years-of-age that readers bring to the words themselves?

The young boy George III. The young children of Abigail and her husband John. The young Connecticut teacher in front of his young students.

To them all, Cato is calling.

For You Now

You’ve been patient in reading this somewhat long-ish entry of Redux. I won’t push it much further. I do want to point out a singular word.

Virtue.

(1511, Raphael, painting on the virtues)

For those on the side of colonial rights in early December 1773, the idea of virtue is central to what they believe they’re doing. Virtue is the energy, the fuel, the foundation of what they want to do in rejecting and removing the East India Company’s tea from the ships in Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, and Charleston.

Virtue. Hmmmm.

I’ll let that word marinate with you. I can’t help but point to another word as you do so—Mohawk.

So much more to say, but I’ll stop it here.

Virtue. Mohawk. And Leslie’s path not taken.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: is virtue a living idea in 2023?

(what does chaos do to virtue?)