Americanism Redux

December 28, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1773

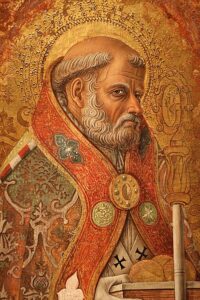

(Saint Nicholas, by Carlo Crivelli, 1472)

“To Sint Nikolaas.”

People holding hands. Arms wrapping around necks and shoulders and waists. Smiles on faces. Laughter and words of happiness and good cheer. People having a pleasant and meaningful time.

Inside is warmth. A story told. Lost loved ones remembered. A song and prayer. Recalling the legacy of a dead, gift-giving legend.

Outside the walls, snowflakes fall and ice forms. A freezing wind howls and the bare branches wave, the thinner trees lean this way and that.

And once more, inside: “To Sint Nikolaas.”

Samuel Waldron and his Dutch family and friends had come together a few days ago at his house and workshop. They held a party at his self-named “Protestant Hall” in honor of the death of Saint Nicholas, or Sint Nikolaas as he was called by these Dutch immigrants on western Long Island, colony of New York.

Today, 250 years ago, with the toasts silent in the snow and icy waters heaving in the Sound, Waldron smashes his hammer against the piece of hot iron that he pulled from the deep bed of glowing coals. White and orange sparks fly. The thickly muscled blacksmith pounds again—ring!, and then again—ring!, shaping the smoking, semi-soft metal. He is the latest member of a family of blacksmiths. He earns his living next to the fire and bed of coals, bellows at the ready to exhale air across the shimmering heat, anvil poised to hold steady at the shock of ringing blows, framed by the smoldering black next to Protestant Hall.

Twelve months ahead and the hammer will pause. Protestant Hall will be the scene of another Waldron’s Dutch celebrations of Sint Nikolaas.

* * * * * * *

Today, 250 years ago, if the world had satellites, we could track the traveling dots, rippling out in circles, in lines, in forms that shift and contort and trace the routes of people over roads, rivers, and coastal waters. Each dot is Boston’s news of last-resort tea-dumping told in hand-written letters, printed newspapers, or oral stories of first- or second-hand accounts. The news spreads, day-by-day, untracked in the black orbit, a boat in the water, a horse on the road, feet on the path.

* * * * * * *

Also outward from Boston are other incidents regarding other tea. Someone finds tea in a home in Dorchester, near Boston, and brings it to Boston Common for destruction. In Charlestown, adjacent to Boston, 1000 people search for tea already purchased weeks ago and now in shops, homes, and storehouses. In a symbolic act of solidarity with Boston’s tea-dumping and Lexington’s tea-burning, they carry in bags and boxes of tea for ignition in Charlestown’s public square today 250 years ago. Flames at noon.

(Charlestown, colony of Massachusetts)

* * * * * * *

In Philadelphia, colony of Pennsylvania, 697 chests of East India Company tea are still aboard a vessel anchored twenty miles away on the Delaware River, at Chester, Pennsylvania. Benjamin Rush and Thomas Mifflin organize a public meeting at the Pennsylvania State House (the future Independence Hall). The same space had been used a few weeks ago when a crowd of a few hundred approved the Philadelphia Resolutions. On December 26, however, 6000 people filled the State House—reminiscent of Boston’s recent scenes at Old South Meeting House—and endorsed Rush and Mifflin’s recommendations that the tea-laden ship at Chester be compelled to return, unloaded, to England. The ship’s captain complied. The vessel departed. The tea undumped. Cold waters flow in the Delaware River.

(State House in Philadelphia, colony of Pennsylvania)

* * * * * * *

In Charleston, South Carolina a guard stands outside the Exchange. The grounds around the building are quiet 250 years ago today. Inside the Exchange are the 257 boxes of East India Company tea that had been carried there two weeks ago for the mutual purposes of protest and safekeeping. The tea is stacked below the brick-lined ceiling, within the brick-lined walls. Rub your hands across the rough surface lit by the lantern hanging on a hook. The contents of this half-dark space embodies a thin, clear line between public action and public order by local pro-colonial rights supporters. They’ll keep close track of events whenever information arrives from the north to the Committee of Correspondence and other outlets. The information’s journey crosses a double layer of gaps—the one between Europe and America and the one between South Carolina and all parts north along the coast, west into the interior, and south toward the peninsula and islands. The people here live in a strange blend of motion and suspension.

(The Exchange, where the tea sits)

* * * * * * *

At 26-years old, Philip Fithian should have it figured out, but he hasn’t. Plenty of people his age have the answer or AN answer. Not him. He’s still wondering, mulling it over, taking measure of himself relative to others. He pours out his feelings on page after page of his diary.

How should I conduct myself in the world at large? Who am I in the company of people? How is it I am in relationship to others?

The questions are all the harder and more tangled because of his job. He’s a teacher, a family’s teacher actually, the tutor of seven children in the Virginia plantation family of the Carters. Rich, important, well-connected, the center of a web-like world. Like you’d expect.

So most days he’s with the Carter children and they’re staring up at him as some sort of role model or authority figure. And in his head he has no idea who he really is among the people of daily life, be it here or anywhere else.

Alone in his room at the Carter plantation home, Fithian thinks about two people with their answers. Mrs. Carter likes people who are open, energetic, lively. Mr. Carter prefers people who are quiet, reflective, stoic. As far as Fithian can tell, it’s a bewildering choice that, once made, sets a course without deviation. Even more confusing is the reality that life flows back and forth across the valley between.

He’s also pondering one of the Carter children, Bobby. He’s noticed that Bobby likes to have his pet dog sleep with him in his room at nights. Fithian thinks of the darkness behind the closed door, imagines boy and animal in bed. He’s relieved the next day when he see Bobby reading from the Old Testament Book of Deuteronomy and knows he’ll see the passage on the page about the evil of lying with animals. That’s what Fithian holds onto in thinking about the closed bedroom door. He’ll need to learn much more in the new year ahead, much more about understanding the human heart, both the love and the fears residing there, the possessor and possessed.

Fithian’s tutoring duties will re-start in a few days when again those seven faces will stare into his eyes.

(Philip Fithian)

* * * * * * *

Dr. John Connolly waits in Fredericksburg, colony of Virginia with a chessboard in his head. The game board covers hundreds of miles of woods, hills, ravines, and ridges where the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers combine into the Ohio River. He wants to access, ingress, and possess thousands of acres in the region. His relationships with political leaders in colonial Virginia and the things they can achieve are the chess pieces. Connolly believes he can craft a set of moves that will affect the outcome. He recommends creation of a new county near Pittsburgh with a county capital and two thousand residents will compel the colony of Pennsylvania to set a western boundary to accommodate Virginia and land-buyers like Connolly. Connolly expects his plan to save residents “from the oppressive Tyranny which is now exercised over them (by Pennsylvania’s colonial government).” It’s only a question of whether Virginia’s power-brokers take his advice to play the game in his head.

(A home in Fredericksburg, seen by Dr. Connolly)

* * * * * * *

Sint Nikolaas, an immigrant group celebrates a saint. Tea chests, the objects of dispute over power and rights. A young man’s straining thoughts, reaching for a grip on the rest of life. Lines of rivers on a chessboard, the squares of dispute over homes and homelands.

A few days of sand wait to slip down the hole of the narrowed glass, the dwindling grains of 1773.

Also

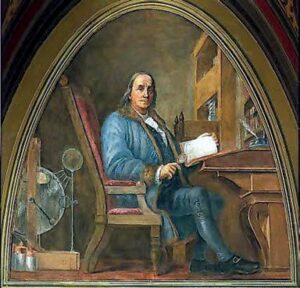

It was at a similar time, in late 1772, when the last days slipped through at the end of that year. In one of them, while in London, England, Benjamin Franklin had received private letters written by Massachusetts’ Royal Governor Thomas Hutchinson and some of his colleagues. The letters contained candid descriptions of the writers’ support of imperial power and their low view of colonial rights. Franklin had sent on the letters in secrecy to selected leaders in the Massachusetts colonial legislature. The letters were made public in spring 1773, making worse an already bad condition in Massachusetts between governing and governed. Franklin’s letters resembled Samuel Waldron fanning the coals into a white-hot heat. Public trust and goodwill turned to ash in the fire. No one bothered to know the path of the letters arriving into public view.

And now a year later in 1773, today, 250 years ago, Benjamin Franklin confesses. He publishes an essay in a London newspaper where he admits to being the person who sent the private letters from England to Massachusetts, though doesn’t reveal how the letters came to his hands. Franklin confessed in order to stop two men at the point of pistol-duelling over which of them had supposedly sent the letters. Franklin prevented political murder. Nevertheless, for his efforts, Franklin has now brought scrutiny upon himself. London’s fiercest opponents of colonial rights begin to plan their vengeance against the famous American printer-inventor-scientist.

They want to humiliate him. All they need is an excuse.

(The Confessor)

* * * * * * *

In Grenada, an island in the eastern Caribbean Sea, plantation owner and political leader Alexander John Alexander writes excitedly to an acquaintance, Joseph Black in Scotland. A.J. Alexander resembles Benjamin Franklin in that he excels at applied scientific research and conducts extensive trans-Atlantic correspondence with other scientists. Alexander’s focus this year has been in observing and recording the health of his enslaved African men, women, and children. He believes the Africans may possess habits and traditions that can help treat diseases and illness among Europeans. Alexander’s letter to Joseph Black is to thank the Scotsman for sending books to Grenada and for encouraging his island research.

Alexander is thrilled to have a letter-writing relationship with Black. Black is a legend in European scientific circles, having researched in combustion. Black asserted that the burning of an object produced a weightless, invisible element known as phlogiston. Almost a century of science was built around the accepted reality of phlogiston, and Black was the high-priest of the phlogiston temple.

Within ten years, the notion of phlogiston will crack apart like an empty shell.

(AJ Alexander’s correspondent, the famous Joseph Black)

* * * * * * *

The toddler watches his parents closely today, 250 years ago. He sees an unmoving figure stretched out. He hears his mother and father talk with emotion, their own bodies leaning ever so gently in the direction of the corpse. A love can be felt in the air. Deep in the little boy’s memory small but clear impressions form, latch, and hold in place.

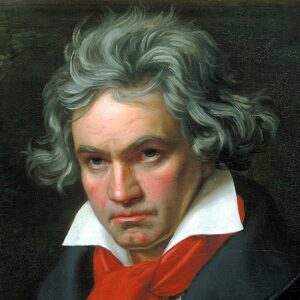

Well-known musician and 61-year old grandfather Ludwig Beethoven is dead. Future genius of classical symphonic music and 3-year old grandson Ludwig Beethoven will never forget.

(the grown-up grandson)

For You Now

It’s late December, when a year winds down and the days fall away. A whole unit of time empties out during the celebration of religions, love, and relationships. You think about what got done, what didn’t get done, and what is yet to be done and carried over into the new year. Discard the container.

Unless something intervenes to make it different, most things at year’s end will have the feel of wearing out in these waning days. The closing of the year will fix and attach, adding to the weight and drag. Through your decision or your acknowledgement, a fading begins and an ending appears. An instinct takes over that calls for the shearing off of dead layers.

But if something does, in fact, intervene at the end of the year, the effect can be jolting. A sudden platform emerges, a spot from which you can jump or leap or sprint ahead. A greater distance into the new year will be spanned than would otherwise have occurred. A greater speed can be reached more quickly because you get the starting force of pushing off.

The tea laws and shipping of spring and summer became the tea meetings and landings of fall and early winter. The most powerful and explosive energy of the months-long event compressed into the year’s twilight. Squeezed into the countdown of weeks to days to hours, the intensity shuddered and rattled within communities of people. Above them, the clouds vanished, the Long Night Moon rose, and the constellation Fornax, or The Furnace as known to the British, burned like the coals in a blacksmith’s forge.

(the Fornax)

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: is there a compelling event, a trend, or an issue that you will carry over and gain life in the new and next year?

(Your River)