Americanism Redux

December 21, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1773

Well, it’s over. And now…

…the waiting begins.

250 years ago today, an east-sailing ship carries five-day-old news across the Atlantic Ocean to London, England.

The present’s big event is a thing of the past that others will discover in the future.

* * * * * * *

Simply put, the event of three days ago, December 16 in Boston harbor adjacent to Griffin Wharf, was a story of steps. All three tea-laden British ships were anchored at Griffin’s. Another mass meeting at Old South Meeting House had produced a decision of next-to-last resort: find out why the ships can’t get clearance to sail back to England with the crated tea still aboard before the clock runs out, and the tea is required through regulation to be landed, unloaded, and paid for. And with Governor Thomas Hutchinson’s refusal to intervene and enable the ships to depart, the thousands gathered at Old South accepted the last resort: to designate a smaller group to disguise themselves, board the vessels by force, dump the tea without additional violence, and return to their homes as the tea disappeared into the salt water.

That’s how it happened.

Approximately 300 tea-dumpers appeared, variously dressed in old clothes, wearing large coats, faces smudged with grease, some of the group with feathers fixed to their hair and calling themselves “Mohawks”, many in the group screaming war hoops, lifted, carried, and heaved 340 chests into the harbor water. No other violence occurred except for that employed against the wooden boxes.

Over the next few days, occasional boxes of tea were seen floating on the surface. A group of watchers rowed out and scooped them up from the water. The participants in the event resumed their daily lives. Some people, fearing arrest and prosecution, slipped into semi-hiding.

Samuel Cooper writes a letter of explanation to Benjamin Franklin in England. “In what Manner it (England) will resent the Treatment we have given to this exasperating Measure is uncertain; but thus much is certain, that the Country is united with the Town, and the Colonies with one another, in the common Cause, more firmly than ever. Should a greater military Power be sent among us, it can never alter the fixed Sentiments of the People, though (it) would increase the public Confusions, and tend to plunge both Countries into the most unhappy Circumstances.”

And so they wait.

* * * * * * *

You can still be active while you wait.

He sits at his desk, holding the quill pen, rolling it between his fingers. Thoughts and thoughts, his thoughts carry him back, more than ten years ago, to the war he fought. He remembers trees and brush, deep ravines and high ridges, gray light in dawn, dark light in dusk. He hears them again, the yells and whoops, a thudding sound of arrows, a gurgling sound of tomahawks sinking into flesh, a popping sound of bullets. He smells them again, puffs of smoke, of sweat sprinting by. He sees them again, blurred bodies, cloth of red, white, tan, and blue.

(an excellent study of The Ranger as shown in Last of the Mohicans–“we damn sure ain’t no militia”)

“I hear we must Fight for our Rights, as all other methods fail,” writes a veteran soldier to his Connecticut audience. He advises them from the tip of the quill pen: “I would have you inform our Countrymen, that I think it will be best to let all our Enemies land without opposition, and we can best fight them and cut off their Officers very easily, and in this way we can subdue them with very little loss.” He reminds them: “You may remember how the French and Indians fought (British) General Braddock’s army (in 1755). That’s the way we must manage our Enemies, and we shall meet with no difficulty I’ll warrant.”

He signs no personal name other than a signal of the strongest of messages:

“A Ranger”. That’s what he calls himself.

The term is a hybrid and synthetic of natural material—colonial American and Native warrior. It is recognizable to everyone. It confers a unique status of special fighter, of someone with a Euro-American background who has embraced the war ways of Natives, of New World hit-and-run tactics, of ambush and raid, of swift surprise attacks and swift sudden withdrawals, of a bloodiness and killingness regarded as uncommon among Old World soldiers.

The Ranger in Connecticut and The Mohawks in Massachusetts, holders and imaginings of special worth.

* * * * * * *

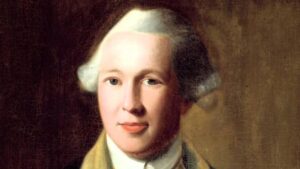

Joseph Warren, one of the leaders of Boston’s tea-dumping mission of last-resort, disagrees with The Ranger. Writing to Arthur Lee in England, he asserts,”It is my firm opinion that a connection upon constitutional principles may be kept up between the two countries, at least for centuries to come, advantageous and honorable to both, I always respect the man who endeavors to heal the wound, by pointing out proper remedies, and to prevent the repetition of the stroke, by fixing a stigma on the instrument by which it was inflicted. This country is inhabited by a people loyal to their king, and faithful to themselves; none will more cheerfully venture their lives and fortunes for the honor and defense of the prince who reigns in their hearts, and none will with more resolution oppose the tyrant who dares to invade their rights. From this short but true character of this people it is easy to see in what manner a wise king or a sagacious minister would treat them. But–!”

Warren leaves the space beyond the “but” purposely unfilled. That’s where the future resides. That’s where choices and options wait to grow before the soil hardens to fate.

(Joseph Warren)

* * * * * * *

Nat hobbles along, leaning hard against his wooden cane. His ankle hurts him, as it always does. One step at a time, mile by mile, a journey of fast thinking rather than fast running. He’s escaped from his enslaver, Jacob Leech of Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania, 250 years ago today.

29 years-old, Nat wears a white shirt and black pants. He’s proud of his new hat but he won’t wear it very often—he’s easily recognizable with its long tail of fur attached.

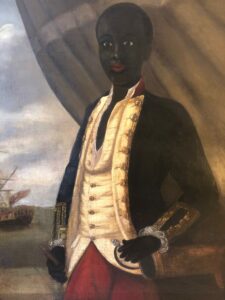

He has a good chance of getting away, of making it to freedom somewhere else. Nat knows how to tan hides, speaks both English and Dutch, has worked the packet boats that carry local trade short distances in river travel, and above all has experience at sea on a privateer, which means he has served as a sort of legalized pirate in wartime. Nat is adaptable, quick-thinking, and not afraid to take a risk. If he can stay away from wine and ale, which have caused him problems in the past, he has a good chance of never seeing Jacob Leech again.

(depiction of an unknown black privateer)

* * * * * * *

Today, 250 years ago, there’s a new book in Philadelphia that would have interested Nat, though he won’t have time to read it. It’s entitled “An Essay On Slavery, Proving From Scripture Its Inconsistency With Humanity And Religion”, by Granville Sharp in London. Robert Aitkin and Joseph Cruikshank offer the book for sale in Philadelphia. The price is reasonable: six-pence for one copy or four shillings for a dozen, if you wish to distribute copies to friends.

Aitkin and Cruikshank make an interesting pair. They’re building from a collaboration started a year ago when they produced “General American Register”. Their publication offered a variety of useful information and advice for daily life, especially in business and trade, (a very early quasi-Wall Street Journal). Since then, they had deepened their working relationship in the dual reality of pro-colonial rights and anti-slavery policies; they were advocates of both. This latest book by the British social commentator Granville Sharp is thus a natural addition to the Aitkin-Cruikshank enterprise for shaping opinion in the Philadelphia region.

(Robert Aitkin)

* * * * * * *

The daily chore of governing is hard at work in Annapolis, Maryland on this day 250 years ago. Maryland’s colonial governing class—governor, legislative assembly, and upper council—slogs through issues affecting a range of life in the colony. They’re working on laws about repairing the office where money is printed, protecting a particular species of deer, offering funds to help the poor, building a light house, and reimbursing the governor for costs linked to hosting various courts of law and stacks of public records.

Life rolls on regardless of the dramatic tea-related events in Boston.

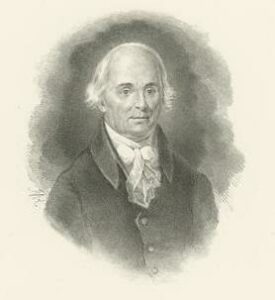

(Maryland’s royal governor, Sir Robert Eden)

* * * * * * *

It all makes sense now, at least to the readers of the Virginia Gazette.

Many colonists were seeing a clear, unbreakable line from eight years ago and the Stamp Act of 1765 down to today and the chaos surrounding East India Company tea. The series of imperial laws and regulations fit together in this hindsight. An anonymous “Gazette” writer depicts the case forcefully to readers along the Chesapeake Bay. “This…is a plain and true Detail of the Dispute between Britain and the Colonies.” The writer concludes, “For my own Part, I do most heartily congratulate my Countrymen on the firm and virtuous Opposition made in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, against the Admission of this Ministerial Tea; and I have no Manner of Doubt but that the generous Love of Liberty, which has hitherto distinguished the Virginians, will unite them in the same wise and well-judged Opposition. I am not mistaken, Mr. Purdie, which I say these are the Sentiments of THOUSANDS.”

(Alexander Purdie’s Virginia Gazette)

* * * * * * *

There’s a stream flowing through the meadow. The land stretching from either of the river’s banks is rich and dark. The stream is at the bottom of a gently rising valley where the soil holds moisture even in dry spells. Thick grasses and beautiful trees mark the entire area. You can easily grow wheat, corn, or tobacco within the sound of the rushing water. Two water-driven mills are only a short distance away by horse-drawn wagon, likely spots where your harvested crops can be ground into marketable grains.

The owners are interested in selling these two thousand acres in Virginia, where the flowing water is called Bull Run. Eighty-eight years later, the first major battle of the Civil War will be fought along Bull Run.

(Bull Run Mountain)

Also

Working in tandem, British King George III and the British Parliament decide in December 250 years ago to suspend the 1740 law that provided for a seven-year naturalization path of immigrants to the British colonies. The British government’s decision effectively prevents immigrants from becoming British citizens in the American colonies. The motivation behind the change was an imperial desire to limit the economic vitality and economic appeal of life for new residents in the British colonies.

Whether planned and projected or not, the suspension of colonial naturalization is yet another measure drafted in response to the growing power of the British colonies in America. George III, Prime Minister Lord North, and their followers in Parliament and throughout England patch another hole in the hull.

An invisible barrier exists for supporters of imperial power and supporters of colonial rights alike—break through it and each side sees excesses, dangers, threats, and malevolence in the other. The barrier is both strong and weak at the same time, massive when seen from a distance but meager when close enough to touch. On the sea’s horizon the ship sails in beauty. Moored at the docks, the ship leaks below the water line.

The best anyone can do is look back in time and learn from experience.

(King George III)

For You Now

The event will be called “Boston Tea Party” a few decades into the future, around the time, interestingly, of the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. But what everyone wanted to prove immediately from the first minute of action on December 16, 1773 was that no one had gone violent, no one had gone too far in their zeal, no one gone overboard with the tea in punching, striking, or shooting someone who contested or resisted or opposed. Everyone wanted to know 250 years ago today—did they turn violent?

The question comes from the same instinct of hindsight shown in the newspaper essays, 1765. In this instance, they wanted to avoid the troubles embodied by Ebenezer Mackintosh and his anti-Stamp Act mob of 1765. Then, homes were destroyed, individual people humiliated and tortured in front of groups, that thin border between civil society and organized savagery obliterated in the fires and screams. It had been as if the Connecticut Ranger had chosen to ignore every restraint in the desire to spill and savor blood. No one wanted a repeat and so the tea-dumpers were careful and orderly.

The urgency of it was all the greater and deeper if, as some were saying, the colonists who resisted imperial laws wanted to do so as a new and separate people, especially if those people believed that virtue was the glue holding them together in rough waters and stormy weather.

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: how do you assess the state of the glue today—is it stronger for the people and forces of the violent or the people and forces of the nonviolent?