Americanism Redux

August 24, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1773

Close your eyes.

To see clearly, close your eyes. Behind eyelids, in the loss of sight, your mind’s eye begins to see. In the half-dark, with trails drifting across your vision and points forming into patterns, settle in to let your mind’s eye open up. Watch the past begin to show on the small screen.

That’s what she’s doing, with her head on the pillow, her gray-black hair matted down in the summer heat.

(like where she stayed)

Her eyes are closed, today, 250 years ago, as she lays on a hard bed in a Queen Anne’s County jail, British colony of Maryland. Her black hair has slight flecks of gray. Her eyes stay closed. The scenes, those awful scenes, form and pass.

A drop of moisture in the corner of closed eyes. Could be the heat. Could be a tear.

Behind the eyelids, from a scene four weeks ago, an animal in man’s clothing. Fists that pound, hands that rip. Hot and sweaty breath. Pain throughout her body. Blood oozing. Her thoughts start with terror, mix with horror, and rush to revenge. The thing that happened that she couldn’t stop.

Behind the eyelids, from a scene two weeks ago, herself tip-toeing into his room, her hands carrying a…stick…a pole…a tree branch? She walks quietly toward his figure. His chest rises and falls with his breathing, the sleeping breath that on her before was stinking and wet. Closer to him. At the foot of the bed. He still sleeps. Closer. The last footstep crosses a faint light, revealing a square blade at the end of the wooden rod in her hand. She pauses. His head is on the pillow. Sleeping. In the seconds, a universe waits.

The blade disappears as she swings the garden hoe down with strength and purpose. His head is her target. The metal strikes skin and cuts deep into his face. Blood spurts and he screams. Target hit. Her emotion ablaze, she raises the hoe again and slashes down once more. He’s writhing with pain—its his own this time—as the blade penetrates his arm, slicing deep and opening a new stream of red. Together they scream, this man and this woman, he from fear, her from vengeance. The sound brings people into the moonlit space. She is grabbed, tied up, and hauled to the place of justice. Someone picks up the blood-stained garden hoe. The man is in agony.

Behind the eyelids, from a scene one day ago, she sees the verdict in the cold stares of the four county judges—guilty of attempted murder and sentenced to corporal punishment of a whip across her back, a cane beaten against her shoulders, or possibly hanging by the neck. She sees herself in the future, dropping her shirt for the lashing and the beating. She sees again her shirt still on but herself set higher than the others, a man pulling a rope over her head and down across her face until he tightens it around her throat. Some of those four judges have enslaved women like her on their acreage and in their homes, and who knows, maybe the man with the rope has them as well. What have they done to their enslaved women?

Today, 250 years ago, the enslaved black woman Hagar is inside the darkness of Queen’s County jail and one day closer to her adjudged punishment. Outside, somewhere, her attacker William Rooke nurses his gashed face and arm. And also outside, though Hagar doesn’t know it, a few men have begun thinking about Hagar and Rooke and what’s best to be done. Across the eastern shore of the British colony of Maryland this handful of people with eyes wide open will start to gather the clues. They’ll want to speak with Hagar’s enslaver, Joseph Nicholson, Junior. Something’s not right.

* * * * * * *

The eyes of 193 newcomers to Philadelphia are grateful for what they don’t see—an ocean all day long. They’ve been here for about a week after a journey across the Atlantic and are spreading out across the city of Philadelphia in the British colony of Pennsylvania, 250 years ago today. They don’t speak or read English, they don’t know British customs, they don’t know British law and courts, they don’t understand any sort of government with a governor, assembly, council and whatever else. Some of the people here look scowling at them—shaking their heads and thinking “they’re different from us and there’s too many of them.” Some do welcome them, especially those who sound like them.

These 193 people, mostly men, came by ship last week, captained by John Osmond aboard his vessel the Sally. Osmond had collected them in Rotterdam, Holland, their point of departure for their journey across the Atlantic Ocean. With such first names as Friedrich, Gerhard, Ernst, Johann, and Adolf, many of these 193 new-arrivals are German head to toe. Will they assimilate? Will anyone want them to? Will life here crush them? However the answers go, Philadelphia is teeming with people of all types and now they’ve added 193 more.

(a replica of the Sally, captained by John Osmond)

* * * * * * *

John Boyle is at work in his printing and book shop a few doors down from The White Dove Tavern in Boston, the British colony of Massachusetts. He’s almost ready to announce a new book for sale that he hopes will bring in the customers—it’s “A Narrative of the Captivity, Sufferings, and Removes of Mary Rowlandson.” The book is a classic by this point, having been printed in more than ten editions since its first release almost a century ago in 1677. The book’s enduring popularity in Boston and greater New England reflects the region’s fascination with its earlier heritage, especially the dramatic tales of war and conflict with Native tribes. The book also hints in no small way at the darkness “out there”–the other side of their sense of British and European civilization. You can’t help but wonder, too, if for them the darkness has a mirrored side “in here”–within the bodies and souls of Christians who struggle with sin and fallenness in an unsaved world.

Boyle, a devoted member of the pro-colonial rights movement, will take cash for his forthcoming book from either place, the outs and the ins.

(the book cover)

Also

A centralized authority figure can declare a major change. But to make the major change a fact, to implement it, some power will need to be used, to be wielded by that same figure.

Otherwise…forget it.

It’s a truism that’s evident today in Florence, Italy. The military unit assigned to the Vatican, the Corsican Guards, are out in the streets of Florence. They’re going to places in where Jesuit priests are reported to be, perhaps in hiding, perhaps not. The Guards are to ensure that the Jesuits obey the Pope’s recent declaration that banned them from preaching and ministering to the public. A centralized leader declares and enforces major change. So far no resistance has been seen.

(the Corsican Guards)

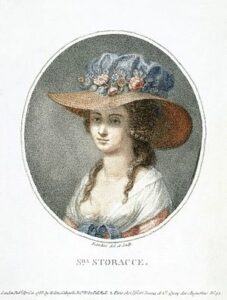

In England, the Italian father of seven-year old Ann Storace could not possibly be more proud. He and his wife watch their daughter Ann sing in front of a public audience for the first time. It’s 250 years ago today and the crowd at Southampton, England shouts cheers of approval at Ann’s performance; there’s no other way to say except that “that kid can sing!” Dad and Mom are already planning for the next concert.

(Ann Storace as an adult singer)

Up the coast from here, up the coast from the Isle of Wight, today 250 years ago, an elderly man stares out at the ocean from a castle on Scotland’s Aberdeenshire coast. He is Dr. Samuel Johnson, said by a local to be one of the most famous men in Scotland as well as England. Dr. Johnson is enjoying tea and coffee in the castle’s drawing-room, where he explains to his travel companion, James Boswell, that it’s the best policy to keep land holdings intact among the nobility so the property can be passed down generation to generation. “If the nobility are suffered to sink into indigence,” he says, “they of course become corrupt; they are ready to do whatever the king chooses; therefore it is fit they should be kept from becoming poor.” Such an imbalance throws the system out of whack, is the implied conclusion. As with most things uttered by the esteemed Dr. Johnson, this remark has the feeling of a sealed completeness, in no need of adjustment, no refinement from further debate and discussion. He places his empty cup on the silver tray.

(Dr. Samuel Johnson)

Earlier today, in a less steady state, Johnson and Boswell had been in a large row boat in the ocean, a short distance from the castle before tea-time. Oarsmen had dipped and pulled the vessel through the water to see one of Aberdeenshire’s most renowned and haunting sights. They were at the Bullers of Buchan, a breathtaking waterway carved into and through the rock by the pounding waves of the Atlantic Ocean.

Seated in the row boat and entering a vast cave made by eternally thrashing saltwater, Johnson had remarked, “What an effect this scene would have had, were we entering into an unknown place.”

His voice echoed over the encased waters. The sound had had the unique volume of never-spoken truer words.

Indeed, over time, the knowledge of Bullers of Buchan had been gained, kept, and passed on, rather like the nobility’s land holdings Johnson described a short time later. Down to the generation that could fit in a row boat and gaze at the power of water on the rocks. The scene begs a question: are the rocks weaker than the land?

(the Bullers of Buchan)

For You Now

In case you’re curious, we will see Hagar again. Be patient and be prepared.

She suffered from the impulses of an outside aggressor and tried to enact her form of justice with a garden hoe. Her fate rests with people like those judges who, in the British colonial world, are smaller and shorter versions of the types Johnson pontificated about over a hot caffeinated beverage. And those other people keep coming in—pouring in, from the perspectives of folks who don’t want non-English speakers—they’re new-found New Worlders because life stinks in the Old World (for context on reaction, compare the 193 Germans in a city of 30,000 to busloads of approximately 700 immigrants to Philadelphia and 1.6 million residents in 2022).

Will they be happy if their new lives amount to replays of Johnson’s keep-land-with-the-nobles observation? Will they find further darkness in the place that looks backward on the darkness of part of its past and inward to the darkness of its own self? Or, in fact, will they decide rather quickly that the Sally brought them to a better future?

And culture, don’t forget culture. It’s an amoeba-like force, shifting, living, adapting. Culture in our story exerts a power like no other—keep in your mind the popularity of the book about a girl kidnapped by Natives almost a century before our story for today. There’s a reason that book keeps selling, edition after edition. There’s a reason John Boyle sets the metal type for yet another cranked-out copy to sell in his bookstore near the Three Doves.

The possibilities of meaning here defy a count. You’ve got to be quick of mind, your mind behind the eyelids, if you want to see the possibilities. Close your eyes.

Suggestion

Take a moment and consider this—why do thousands of people today want to come to America? Is your answer something that gives you hope or gives you concern?