Americanism Redux

April 27, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago today, in 1773

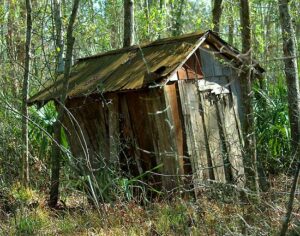

A black man sits in a small wooden hut in the woods of the Hudson River valley. It’s been made, hastily, just for him. Up until a few days ago, he was working with a crew digging for iron ore. He was one of the best workers on the crew. It was back-breaking stuff, shovels and pick-axes powered by massive arms and shoulders, and they were having no luck finding any mineral deposits deep in the ground. Then everything changed. Work stopped when he fell ill. Small, pus-filled bumps have formed on his body. Smallpox, killer of millions. For now, he’s still alive, still fighting for life. He’s been offered a treatment that has helped lots of people—inoculation. He refuses. He doesn’t trust it. To him, inoculation is insanity. He waits to see if tomorrow comes. Alone, in the hut.

(he waits)

There’s a fierce competition in Providence in the colony of Rhode Island. Three doctors are seeking patients and will stop at nothing to entice them to their doors. Dr. Daniel Hewes believes his best competitive edge is detail—he writes in a newspaper about his extensive medical casework, his variety of medical skills, and, intriguingly his desire to focus on two target patient-groups: women ready to give birth and people in need of having bones reset. For the latter group, Hewes highlights his recent experience at having received the corpse of an enslaved black man. Hewes made the corpse into a skeleton and inserted wires into the bones for an educational and marketing display. He hopes patients will feel more comfortable seeing his exact methods: “I’ll connect here to here…”and so on. He’s waiting for new patients to flock in.

(a home in Hewes’s Providence)

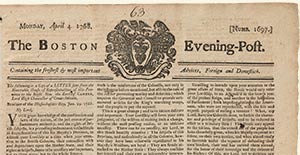

Readers of yesterday’s Boston Evening-Post are digesting two sides of a single thing. On one page of the newspaper is an eloquent essay about the need to end slavery. The writer elaborates on Biblical references to the twelve tribes of Israel and the theory that one tribe can be traced to enslavement. On another page of the newspaper is a rather standard advertisement to purchase enslaved black people. Put another way, on one page enslavement is an issue in need of change, while on another page enslavement is a practice in a state of continuity.

(the Boston Evening-Post)

A Christian missionary staggers out of the Muskingum River in what will one day be called Ohio. Exhausted, sweat-soaked, aching. He’s part of a small group of people canoeing on the river. He wants to convert Natives to Christianity; a few Natives are with him on this journey. It’s been a hard day because the river is shallow. The missionary and the Natives have dragged heavy canoes across the stones and dry river bed. Only occasionally today have they been in the canoe in the water. By late afternoon they’ve stopped. The Natives quickly built a sweat lodge to relax in. Soon they feel better and, refreshed, go out to hunt buffalo for an hour or so. The missionary, sensing that the lodge is the Natives’ exclusive custom, chooses to sleep. As night falls, thousands of spring-peeper frogs fill the trees and choke the air with their croaking. It’s ear-splitting. Sleep never comes to the missionary. The Natives don’t mind.

(the Little Muskingum River)

Today, along a different river valley, the Rio Grande, is a group of Native people called the Tarahumara. To them, an isolated life is a splendid life. They’ve adapted to a terrain that is forbidding, harsh, and horrifying to many other people. Their adaptability has made them unusually skillful runners, capable of covering miles of difficult landscape on foot. Now, they are adapting in a further way as well—they have allied themselves with the Apache tribe in making war on Spanish colonizers. Few Spanish soldiers want to enter the mountains, valleys, and deserts where the Tarahumara live. The Native alliance fights on.

(modern-day Tarahumara runner)

Also

Today, several sheets of paper lay atop a long desk at the front of St. Stephen’s Chapel in Westminster, London, England.

The Chapel is the regular meeting site of Parliament’s House of Commons. The papers are the latest bill on the East India Company, a preliminary final draft of a proposed law. Members begin to straggle in and take their seats on either side of the hall. Low voices fill the air, along with a few coughs, occasional shouts of welcome, and the sound of boots and shoes on the floors.

Lord North, prime minister in the Commons, holds up the paper. Debate—with all the statements, retorts, questions, answers, claims, counter-claims, accusations, and rebuttals—is about to begin. It’s making sausage by chewing pork.

The bill’s key sections:

1,400,000 British pounds (money) to relieve the Company;

The Company enacts important internal reforms;

No dividend payment on stock above 6%;

The dividend can only be raised after the Company has paid off at least 1,500,000 British pounds (money) on money owed to the government;

No further territorial expansion of the Company until agreed otherwise;

The Company will sell its product (tea) in the British colonies without any extra fee (or duty) owed in the colonies, along with a Company payment to the British government of three-pence for each pound of tea sold.

The deal is now out in the open.

For You Now

What kind of governmental action has the biggest impact? Setting aside the good and bad and right or wrong of it, what is the action of government that affects the most people, or, the most of a particular type or category of people?

The East India Company is a significant economic organization in British life, no doubt. And its product, tea, is a part of daily living. And so too is its geographic footprint, whether in actual square-mileage and acreage inland from the Indian Ocean or in influence and recognition in the halls of Parliament.

But no one really knows for certain—Benjamin Franklin, as we will see in a few months, is an exception—how far the effect would run of any major new law regarding the EIC in spring 1773. Indeed, if anyone has any expectation it points to the other direction—to how constrained and minimal the effect will be. The assumption is that it’s not a big deal.

When you look at the four stories today of the ill black man, the doctor, the missionary, and the isolated tribe, this point about the unknowability of the proposed EIC law is all the more compelling. It feels impossible to tell the span and range of impact, so much so that it begins to suggest a limited one.

We’re left with this—a product that is in many homes and households, and an entity that is, at most, among dozens and scores of other entities in the collective minds of government and public.

Which should suggest something to you…

…that other things already have to be true if suddenly a gigantic impact shakes the ground on either side of the ocean.

Suggestion

What is already true right now that makes you concerned about the condition of the American nation? What is it about the present that might worsen in the future?