Americanism Redux

April 18-19, your today, on the journey to the American Founding, 250 years ago, in 1774

The difference a time makes.

It was only a few hours ago. A few days ago. A few somethings ago. Time can take such a short form and yet appear to be so long ago.

Is it the same for time yet to be? Is the future as far away as the past?

No, because there’s nothing between us and the future, nothing like all those things that have filled up the mental space between us and that short time ago.

It seems like only yesterday when…

It seems like tomorrow won’t ever form in a way that is different from now.

(Only Yesterday, the film by Isao Takahata)

* * * * * * *

He’s 62-years old. Good ol’ Henry. Henry Putnam. He loves his family, his wife and kids, the siblings still living. He loves the cousins and nephews and nieces. You don’t walk far in Medford, colony of Massachusetts, without bumping into a friend or relation of Henry Putnam.

He loves that story of his—about when as a young man he stayed overnight, fell in love with a girl named Hannah who lived there, and married her the next morning, but only after he and Hannah brought a couple of cows to her father for a dowry. Henry and Hannah have a heckuva of first-date story. Who cares how true it is? Hardly anyone.

Seems only yesterday that they drove that pair of cows or pigs or unicorns or whatever to Hannah’s dad.

No one knows it and no one would believe it if they could be told, but Henry has a year and a day to live. A few of his family have the same 366-day fate—several of the Putnams will answer the call to duty to turn out–“TURN OUT!!”—to meet the Redcoats a few hours after Paul Revere rides by on his horse. Some Putnams will be shot up and hurt bad. And though no one ever expected a 62-year old man to pick up his musket and man the wall near the Russell house, Henry will do it and Henry will die, ripped away from the family he loves today, 250 years ago.

Seems like only tomorrow—and a year from now.

(near where Henry will die)

* * * * * * *

Twenty miles away from the happy Putnam home, three enslaved black females look to each other for the comfort of family without a last name. One is older, that’s Dinah. One is younger, that’s Cato. One is youngest, that’s Deliverance. By the end of today, 250 years ago, they’ll be completing their first day as purchased human property in possession of a brickmaker, Jeremiah Page, designer and builder of his home, Page House, in Danvers, colony of Massachusetts. The three last-nameless women of varying ages will live out back in a wooden shed. The bonds of love, caring, and affection that they will share are the bonds of love, caring, and affection they can make. Page makes bricks. They make connections. You build with what you have.

Brickmaker Jeremiah and Sarah, his wife, have an ongoing dispute about the tea protests. He forbids the use of tea in his home. She invites her friends to sip tea on the “widow’s walk” atop the house, thereby keeping to her husband’s decree while still enjoying tea not inside the home.

No one offers tea inside or out to Dinah, Cato, or Deliverance.

No one knows now but before the crows start picking at the summer corn, a British Redcoat General, Thomas Gage, will demand use of Page House. And the tea ban be damned.

By then it will seem like only yesterday—the house was home to a different world where old lines of authority once ran along the brick and wooden walls.

(The Page House)

* * * * * * *

James Lloyd Chamberlain raises his hand and calls out “Aye!”. His voice joins many others on this day 250 years ago in Annapolis, colony of Maryland. He and his fellow members of the colony’s Assembly have just voted to set a new rule: a minimum of 34 elected representatives must be present before a Speaker can be voted upon and chosen. The intent is to use this new standard when the next Assembly meets.

Hold on, though.

Another vote is immediately called, and James Lloyd Chamberlain again raises his hand and shouts “Aye!” He and the group have agreed to defer a final decision on the 34-member rule until the Assembly’s next meeting in July. A contradiction? Not at all in Chamberlain’s view. It’s giving things time, time to settle, time to absorb, time to bring people together.

Tomorrow is the final day of this third session and Chamberlain is satisfied with the result. His final two votes have, practically speaking, amounted to folding up the documents, cleaning off the desk tops, and sliding in the chairs. The business of government is now tidied-up for tomorrow’s adjournment. July? Well, that’s not far off, only a little over two months away. No one in their right mind would expect a repeat of the flood-tide pace of events Chamberlain and his companions have had since this whole tea issue flared up.

And think of it, seems like only yesterday that five months back we were talking about horse races, building projects, and tavern dinners before the next Assembly vote. No, worry not, July will do just fine.

(just around the corner)

* * * * * * *

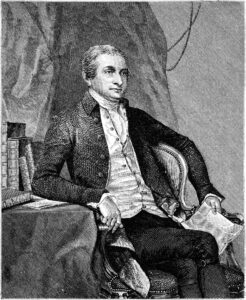

29-year old John Jay stands and watches the signing of the document on the desk. A quill pen dipped in ink, scratched in a flourish across the stiff, tannish-white colored paper. Eyes in the room follow the motions carefully, the movement of hand, the tilt of the head, the slight bent-over posture of reaching a document flat across the top of the desk.

John is “witness.”

These proceedings are for expensive, high-priced, and still higher-quality silver ware and other silver-made items. After a death, they’re being distributed among selected members of the vast Jay and Jay-adjacent family network.

Having finished his witnessing duties, John turns his mind to the thing that increasingly dominates his thoughts—the boiling tea protests in the colonial port-towns, especially his New York City, the site of calls for a “congress”, the first expressions of “Native-disguises” for protestors, and serious early signs of potential violence against opponents of tea resistance.

John reads about the protests, talks about the protests, debates about the protests, ponders over the protests, and both dreams and nightmares from the protests. Perhaps most of all, he worries and fears because the protests have split his family into two parts—one pro-colonial rights and one pro-imperial power.

If only it was like the silver. Sure there could be a squabble about who gets this knife or that platter, but you could always invoke the healing power of passing family history in the form of silver from one generation to the next.

Why it couldn’t be any more than just yesterday when he’d lifted that particular wine goblet and…nevermind.

(John Jay, a few years after witnessing)

* * * * * * *

As John Jay watches ink dry on the parchment and polish gleam on the silver cutlery, Captain Benjamin Lockyer stands on the deck of his British vessel. He loves the sea and the salt air. He’s a mariner, a born sailor, the runner of a tight ship.

He’s also wondering what in God’s name to do next. He’s hit on it—a good idea for tomorrow.

He and his vessel are within hours of seeing Long Island. A short time later he’ll sail into New York harbor.

Except he’s not going to do that. He’s got 698 chests of East India Company tea on board his ship, twice the amount destroyed at Boston. He’s got zero information on how the cargo will be treated after it reaches port—will it be seized and dumped? Will his crew be injured? Will there be a fight, a brawl, a confrontation with people disguised as Natives?

Lockyer is going to wait for a day. Afer reaching Sandy Hook on Long Island, he’ll come to a stop, send out messengers to find out the tone of things, to sound out the depth of likely trouble, and plot a course from there. Today, 250 years ago, Captain Benjamin Lockyer has come to this decision.

It seems likely only yesterday when he didn’t have these headaches. All the storms were at sea. Now the sea is the safe place.

(waiting at Sandy Hook)

Also

A man stands in Parliament’s House of Commons. He begs leave to share his thoughts with his colleagues. It’s a speech. But, oh, what a speech.

Made by a man who—beginning two centuries later—will be regarded as a key founder of Anglo-American conservatism. Books and articles will be written, conferences and symposia will be held, medals will be cast and awarded. In his name, in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Edmund Burke. Fair-skinned. Clear eyes. His thick hair turning color with his aging, a mix of softened red and whitish gray.

Today, 250 years ago, Burke speaks to the elected members of Parliament, glancing first down, now up, flipping page to page in his remarks. It is a performance and tour-de-force. Rock-like logic and morning-breeze tone.

His points are these: 1) the “Americans” did not seek additional repeals after the Stamp Act was repealed, thus allowing for repeal of the tea tax; 2) we need “large and liberal ideas in the management of great affairs”; 3) the tea tax is nothing more than a tax meant to protect a preamble, the Declaratory Act of 1766; 4) Britons once felt as Americans do now, as John Hampden in the 17th century stood on principle to refuse payment of twenty pounds owed; 5) our dignity is at war with our interests; 6) we have already declared we have no intent to impose taxes to raise revenue, which we now have violated; 7) a new colonial system began after 1764, driven by war and war-making; and 8) our best course is to repeal this new system and return to the former ways, when we lived in empire together on two sides of the Atlantic.

At the bottom of the fifty-seventh page, Burke stops. Done. The response is heated, the reaction electric, the result unchanging.

It seemed like yesterday when he was fresh-faced, a young man seated in the gallery, watching the representative body of the British government, before winning his seat in the group.

(Edmund Burke)

For You Now

The future is an alternative universe.

It is a place containing events and actions incomprehensible and unimaginable to a person in the present. The clash heard ’round the world at Lexington and Concord—where the stars spin at a distance of 366 or 365 days away—is an echo of a sound unmade. Blood flows silently until the surface is torn open.

An aging man, and the year left in his life.

A household comprised of a husband, wife, children, and three enslaved people, and the weeks before their house turns upside down.

A colony’s legislature, and the assumption that summertime is the right time to decide rules calmly.

A witness, and the scheduled distribution of valuables across a family network with widening divides.

A ship captain, and the hope that twenty-four more hours will bring crucial information.

A brilliant orator and thinker, and fifty-seven extraordinary pages to recover the past and reverse the future.

Is there anything that any of them can do to see ahead? Can they, be it Burke or anyone else, find the way to shape the future from their time in the past? The surest way to gain nothing is to go nowhere.

Both journeys and explorations start in the present. They begin now.

(first step in each direction)

Suggestion

Take a moment to consider: what can I find in the past that I can carry into the future?

(the deep water of Your River)