Americanism Redux

November 30, 250 years ago today

Some strings are invisible. They exist out of sight until you’re reminded that they’re there. Serving as ties to home, family, place, beliefs, dreams, and dozens of other things, these strings bind your life together. You may lose track of them in the bustle of daily life, but they won’t lose their connection to you. Making them takes time. Cutting them is painful. The story of strings is dramatic, joyous, and tragic.

On this day, 250 years ago, the strings in the lives of two men run toward a 66-year old man with long gray hair and shining gray eyes. One man writes to the old man. The other man thinks of the old man.

The old man, the object of the letter and of the thought, is Benjamin Franklin, who sits today in a house in London, England.

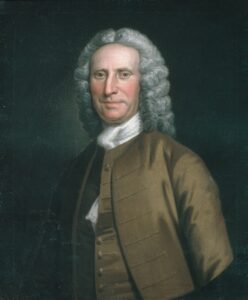

(Cadwallader Colden, David’s father and Franklin’s friend–no known photo of David exists)

Written 250 years ago today, David Colden’s letter to Franklin begins thus: “The attention you pay to every Invention that promises either utility or amusement to Mankind induces Me to communicate to you a very simple Machine which I have made this Year for sowing seeds in Rows.” Colden has designed a plow for farming and hopes his father’s friend, Benjamin Franklin, can introduce it into the most influential circles of science and business in England. A life-long New York colonist from a powerful political family, the 39-year old Colden knows if he makes it there in London, he can make it anywhere, to paraphrase a song generations into the future. And Franklin is the one to make it so.

Thomas Coombe is a minister in the Anglican church, a native colonist of Philadelphia which is also Franklin’s adopted home-town. Coombe is 26 years old and today, 250 years ago, he has been named Assistant Minister to Christ Church and St. Peter’s Church in Philadelphia. It’s an honor, a big step forward. Coombe remembers that a pivotal person in this achievement is Benjamin Franklin, whom he lived with for several months while spending an extended four-year visit and tour of England. Today’s announcement occurred because Franklin opened many doors for Coombe in England. Franklin knew the people who knew the people who took Coombe in the room where it happened, as another and later song would put it.

(Christ Church in Philadelphia, site of Coombe’s assignment)

The best way to bring an invention to light and to success runs through Franklin, who is in England.

The best way to gain advancement in a chosen profession and calling runs through Franklin, who is in England.

The absolutely fundamental truth of the best way for personal illumination and promotion is to invert these statements—flip the facts—first, you have to get to England and, second, it’s a real bonus if you also know Benjamin Franklin.

Also

Today, 250 years ago, the strings have tightened in a meeting of the month-old Boston Committee of Correspondence. The committee’s members have agreed on a plan and formula for organizing and distributing information about the rights of people in America. They have voted to produce the recent “Statement” as a pamphlet, a small, soft-bound booklet easily carried, easily handled, easily used. They will send a specific number of copies to specific people in towns and villages across Massachusetts and from there to other communities as chosen, an equivalent of a second concentric ring of audience for the pamphlet. They will also develop a list of decision-makers and influence-makers who should receive the pamphlet. Moreover, recipients will be encouraged to make their own plans for spreading the pamphlets into third and fourth rings of readership. Out and out and out it will go, the information offered on the rights of people living on the western side of the Atlantic in British-held territory.

The “Statement” pamphlet is a mixture of old and new strings. The unknown is whether the strings can stand up to being stretched over water.

(The Pamphlet)

For You Now

So much more than politics is in play here. We’re seeing the fibers, the threads, the strings of life pulled this way and that well beyond political viewpoints.

Franklin is in England because he enjoys being British and sees it as how success is secured. The celebrity he knows—and celebrity is exactly the word for Franklin by late 1772—required acceptance in England. His acceptance was unique as a combination of recognized scientific knowledge and rustic colonial backdrop. Wielding the combination, his prominence reached its highest points because he was in England.

Colden and Coombe know it, too. They’re trying to live it as well. They are of the New World but fully realize that lasting elevation builds from England outward.

People will need to examine the strings. To discard British rule is to know which strings to cut, which strings to reattach, which strings to weave and make. People like Franklin, Colden, and Coombe will be compelled to look at the strings. And yes, the same is true for thousands of other people with thousands of other strings, some of which are chains and have a nature all their own. Maybe the most amazing thing is that some in the chains will find a way.

Postscript: Colden will die in obscurity in 1784, unusual in his family. His wife died the year before. His father, Franklin’s friend and former governor of the colony, will die four days after British Redcoats seize New York City in 1776. Coombe will waver on independence and finally decide that his life is English; he pursues his religious life in England. Franklin will become one of the most significant “Founding Fathers” on American River. Among much else, he will attempt to deal with strings and chains.

Suggestion

I wonder how you might answer this fill-in-the-blank: “The String I could never cut is___.”

When you’ve done it, put yourself back in 1772 and think about what your answer would have meant then.