Americanism Redux

November 2, 250 years ago today

Dozens of candles and lanterns glowed against the walls and columns painted in white. The flickering light revealed each delicate wave and curving line in the glass of the window panes. People talked, loudly and in urgent tones.

A vote was called for. Hands raised up. All in favor. Yes. Passed. Gavel smacks down. Murmurs rippled around the filled seats of the second floor. Adjourned. Good night.

Through the glass a black night surrounded the hall in the center of town, surrounded the town which was the capital of the colony, surrounded the colony which seemed the center of anger, distrust, and a cold hatred of the British Empire.

“There never was a time,” John Trowbridge had told John Adams last week, “when every thing was so out of joint.”

Across the candle-lit ground floor of Faneuil Hall in Boston, Massachusetts people got up from chairs or benches. Most headed toward the doors while small groups of five, three, or two people huddled in the hall.

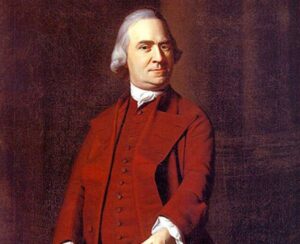

Among them was John Adams’s cousin, Samuel Adams.

He was exhausted but he was exhilarated, too. He’d worked for the past four weeks to convince other members of the Board of Selectmen that the British threat was not only real but immediate, scarcely inches or days away. The British-appointed governor and lieutenant governor were part of the threat. Adams had met day after day to make his case—British authorities would take control of public money, take control of the judicial system, take control of weapons, take control of property, take control of nearly everything. We must, he said, awaken to the threat before it is too late.

He’d proposed the formal organization of a group of twenty-one people. Called a Committee of Correspondence, the purpose of the group would be “to state the rights of the colonists and of this province in particular as men and Christians and as subjects; and to communicate and publish the same to the several towns and to the world as the sense of this town, with the infringements and violations thereof that have been or from time to time may be made.”

And tonight, it was done. His efforts had succeeded with a resounding “yes” vote. Tomorrow, the first meeting of the Committee of Correspondence would be held.

In the formal residence of power a short distance from Faneuil Hall was the bull’s eye of the target, the royal governor of Massachusetts, Thomas Hutchinson.

Hutchinson knew about the vote. He perceived that he knew something more, the real intention of the vote and the establishment of the Committee of Correspondence. Unless it was stopped now, Hutchinson feared, Adams would begin calling openly for a new American nation independent of the British Empire. And then he’d gain the Board of Selectmen’s approval, then the Massachusetts legislature’s approval, then onto other towns in other colonies, and then…

Toward the docks, about a half-mile’s ride from Faneuil Hall, midnight’s chimes would soon ring out from the belfry of Old North Church. The homes of Adams and Hutchinson had gone dark.

Also

By the eleventh month of this year of 1772, two great forces were at work across two oceans.

First, a pair of groups from Massachusetts had used the newspapers to fire essays and lob articles back and forth at each other. One group, which included Samuel Adams, had written in vivid language about the potential losses of colonial liberties and freedoms. They laced their words with references and images of God and the Bible, especially Satan the fallen angel, and also of ancient Greece and Rome. In every shadow they saw imperial wrong-doing. The other group, largely Governor Thomas Hutchinson and Lieutenant Governor Andrew Oliver, had blasted back with explanations of policies and denunciations of people who lied and deceived those ignorant of public affairs. In every complaint they heard local ingratitude. Group on group, both sides fired and counter-fired, lobbed and counter-lobbed, in conflicts waged on the pages of pamphlets and newspapers.

Second, in England and largely concentrated in London, a group of people connected to the British East India Company (EIC) had pushed every lever and pulled every string to find funds for propping the EIC. Granted powers, rights, and privileges in India and the rim of the Indian Ocean for the past 172 years, the EIC was struggling to hold its grip over a restless native population economically, politically, and socially. A victorious war over the French in India back in the 1750s and early 1760s hadn’t gone very far to steady the future.

If these two separate forces would ever join up, no one could tell.

For You Now

Pull back a step and consider it.

In a community, like-mind people organize despite coming from a variety of backgrounds and circumstances. They receive official approval as a part of local government. They gain a single purpose, to spread the word, their word. Perhaps the model will be replicated in other communities.

They will drive home the necessity of making a fundamental change. The time-table is impatient.

Their emergence has marked a change of another sort. Before now, they had been limited to communication in print media meant for local or semi-local audiences. The same was true for the other forms of communication available to them, church-based sermons or tavern-based chatter.

But now a key shift has happened. They are part of an established structure, with recognized powers and duties. They have a clear message and a clear field in which to spread that message and thus link with other like-minded people in similar standing.

It is the ability to share information more quickly and sharply than had been previously possible. The potential is explosive in a “time when every thing [is] so out of joint.” John Trowbridge would understand.

Suggestion

Seek to discern the change that, in our recent months or in the months ahead, rises to the level of the Committee of Correspondence.