Americanism Redux

December 14, 250 years ago today

The baby, a day old, sleeps. Tiny eyelids, soft skin, the wispiest of wispy hair. Fingers are curled. Invisible breaths in and out, the chest rising and falling less than a sixteenth of an inch.

Perhaps now is the perfect time for mother to catch a quick nap. She’s not really sure. It’s her first baby. Phebe, the mother, is 19 years old.

Phebe lives on a farm purchased by her 37-year old husband. Phebe had married a widower whose first wife had died three years before. Phebe was part of a blended family with her husband, three step-children, and their day-old new-born daughter, today, 250 years ago.

A spirit is alive in this town. Nearby, two rivers run swiftly and mill wheels dot the banks. Wood saws, millstones, and cloth machinery work with the flowing water. Activity, motion, energy, and bustle, it’s in the air. It’s also in the Henshaw house where Phebe lays down to nap, Ruth remains asleep in the crib, and the blended family savors a winter’s life on the farm. They will talk and act and do and love.

The chilly waters of the Blackstone and Quinneboag Rivers continue to run in the world of Phebe Henshaw.

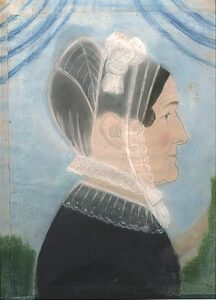

(Phebe’s daughter as an adult, Ruth Henshaw Bascom, noted American painter)

Today, 250 years ago, Samuel Adams worries that he’s lost or losing a friend. Relationships don’t come easy to him. He is outspoken, driven, unsparing when he’s convinced he’s in the right. He’s also focused to a point most people don’t share—”the Opinion of others I very little regard, & have a thorough Contempt for all men,” he writes to his friend, “be their Names, Characters, and Stations what they may, who appear to be the irreclaimable Enemies of Religion & Liberty.” Adams urges his friend to remember to pass along his care and concern to the friend’s family.

Samuel Adams is also directly in front of the people of Boston, today, 250 years ago. That is, those of them who read today’s edition of the Boston Gazette. The newspaper prints an article written by Adams but posing as “Candidus”. In the article Adams-as-Candidus blasts another newspaper printer for falsehoods and inaccuracies in describing the recent council meeting where the pro-colonial rights Committee of Correspondence was established. Adams-as-Candidus accuses this printer of minimizing the number of people in attendance at the council meeting and hinting that the vote to start the CofC was purposely held very late at night. Adams-as-Candidus roars from the page about the bigger issues involved: “The Ax is laid at the Root of our happy civil Constitution; Our religious Rights are threatened.”

Anxiety over a relationship status with his friend. Outrage over a media outlet’s reporting of his cause. In Adams’s house at day’s end the logs glow red and orange in the fireplace.

(Boston Gazette, where Adams’s article appears)

The answer, he hopes, is in a box on board a ship in the Atlantic Ocean. Traveling east to west, the box and the ship left England two weeks ago. Inside the box was a packet of letters. The letters should help, he thinks. They’ll help lower the anger and pour water on the fire that threatens to burn out of control.

250 years ago today, as Phebe Henshaw and her baby daughter Ruth sleep, as Samuel Adams repairs a friendship and recovers lost rights, Benjamin Franklin believes he is helping the Henshaws, the Adamses, and every other individual and family throughout Britain’s North American colonies. Franklin has received secret letters from New England, letters written by the British-appointed Governor of Massachusetts, that describe in detail how British officals can destroy and defeat the colonial rights movement. The secret letters are in the box.

On his own as a paid lobbyist for the colony of Massachusetts, Franklin had decided to write a note to a member of the Massachusetts legislature, instructing him to “leak” the secret letters to specific colonial leaders in greater Boston. Franklin believes the impact of the “leaked” knowledge and “behind-the-curtain” information will show these leaders that the real enemy and threat to colonial rights is not the British government in England but rather a handful of British-appointed political hacks in Massachusetts. Franklin further expects that this will allow the pro-colonial British prime minister, Lord Dartmouth, to also work to lower the intensity of disputes between the imperial government and its North American colonies, especially Massachusetts.

Franklin has also lately completed meetings with Dartmouth. He has implored the British prime minister not to inform King George III of a recent petition sent from the Massachusetts legislature to the British government. The petition is in the language of Adams—passionate, fiery, full of conviction in the rightness of pro-colonial rights and the efforts of British policymakers to undercut them. The best Franklin can do is to say that he will reconfirm with the Massachusetts legislature, through ocean-going letter, the need to present the petition to the King. Dartmouth promises to withhold the petition until Franklin gains his reconfirmation from the other side of the Atlantic.

Hour-by-hour, the letters in the box travel closer to Boston Harbor. Surely they will douse the fires burning inside the empire.

(like the secret letters on the ship)

Also

Today, 250 years ago, Lord Dartmouth calls to order in London, England the scheduled meeting of the Board of Trade and Plantations. The Board has a mixture of power and influence over British policy toward the colonies in North America, subject to King and Parliament, of course. Dartmouth reads aloud a note written by a Board member, the Earl of Suffolk. Suffolk invites the Board to consider a recent case from Africa’s west coast, at Elmina, headquarters of Britain’s West Indies Company and a slave trading outpost and fortress under the jurisdiction of a Dutch governor. The Dutch governor has caused a British ship, the John, to be damaged at Elmina. The Royal African Company, a slave-trading corporation approved by the British government, is seeking compensation.

It’s a solvable problem, in Dartmouth’s view.

(Elmina Castle and Fortress, a slave-trading site in Ghana)

For You Now

You know there is an American Founding. The people in this day’s story do not know that. The most that they know then about their lives is the most that you likely know now about your life—that a real problem appears to be at hand.

And then, following that recognition, they will add another statement of belief about the apparent problem: it’s true; it’s not true; it sort of true; it’s solvable; it’s not solvable; and on and on. It’s the pairing of the two beliefs that will go a long way in the unfolding of the story.

Benjamin Franklin is hoping for reconciliation, trying everything he can from his perch in England to make it happen. He’s pulled from opposite directions.

Samuel Adams is hoping for the proclamation and protection of rights of people in the colonies. Like Franklin, he’s trying, except that for him trying means pushing, driving, forging ahead from the center, from the dead spot.

Phebe Henshaw is hoping for a life of health and happiness and harmony, all within whatever else may or may not be happening in the world around her. She’s not oblivious to it. It’s just that the next big sign is not immediately in front of her.

Lord Dartmouth sees another issue of empire cross his desk and the meeting table. He is part of the group that tries to keep the thing together, handling one problem at a time.

You’re following them and thousands of people like them along the path toward Founding. They tumbling, stumbling, and fumbling their way ahead. In that they would surely see much of themselves in you today, 250 years later.

Suggestion

As you think about their path to Founding, ask yourself how far around the corner you believe you can see.

(your corner)