Now And Today, September 17, 2020

It just goes and goes and goes. Our pandemic. Where’s the edge? I can’t see it. Where’s the end? I don’t know. Where’s the clarity? Good luck finding it. So you continue, the slog continues. You do your day the best you can. More masking, spacing, and limited face-to-facing. If you have anyone in any form of schooling, it’s another day of figuring that out, too, which is likely the worst part of it as well as the worsening part of it. Through it all is the rest and the others: they who don’t, who won’t, who refuse to do what you’re trying to do. Your goal with them, perhaps, is not to burn bridges and not to cut ties. Another day.

Then, September 17, 1918

Two follows one. Second follows first. Again follows before. Coming back, influenza on September 17 was coming back into the lives of the people and the life of their nation. Americans knew enough about influenza from the spring—from the season of buds and blossoms—to know that a return of the illness was noticeable around them in summer’s final days of drying leaves and dying grass. But at the same time, they see that within the familiar and recognizable was a difference, a strange unknowable.

Two is not simply one plus one. Wave Two might not be Wave One repeated.

They sense it in New York City. Today, the city’s board of health votes to do something which is, for them, the first time ever—they adopt a policy to report influenza as an official disease, a documentable thing, a statistic, a category. Around the room where the decisions are made each person raises a hand and votes “yes.” Let the data gathering and the data analysis begin.

More than 500 men vote “yes” in a different way today at the Great Lakes Naval Station north of Chicago, Illinois. They stumble into the facility’s hospital with raging fevers, congested lungs, and bodies that ache like they’d been pounded with hammers. Doctors, nurses, and volunteers stare at one another as the sick men staggered in. They fill up the beds before the experts fill up the sheets of lined paper to track reality.

Which is more urgent—the person, the bed, or the paper?

Today is just three days before Clarence Post’s 27th birthday. He is a private in the US Army, born and raised in Brooklyn, New York but now serving in Dover, New Hampshire. He’s not feeling well and goes to Wentworth Hospital in the town. A newspaper writer notes today that the town has its first case of influenza.

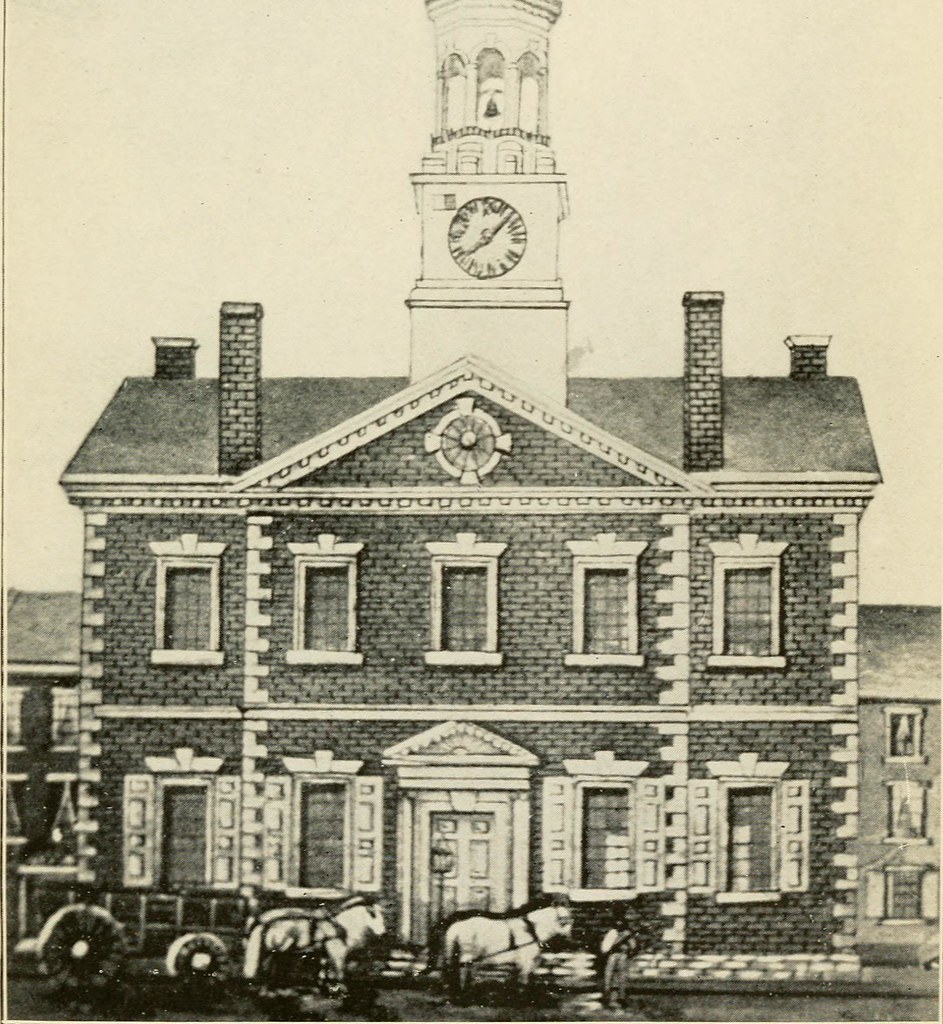

There’s a newspaper in Lancaster, Pennsylvania that cranks out its normal publication today. This representative of American media has one of the best titles of all time—“The New Era”, operating since 1877, a kind of symbol of the new industrialized capitalism that began locally around the 1870s. A writer in the New Era has decided to print a report of the town’s first case of influenza along with rumors that dozens of others are similarly infected. The writer is another one of those people who senses an influenza problem is afoot.

The writer doesn’t know it but The New Era will cease its operations in two years, around the time of the pandemic’s disappearance. In a way, The New Era will have gotten old. The door will then open on another new era, the world after the pandemic.

Lt. Colonel Philip Sloane is director of the Health and Sanitation Section of the Emergency Fleet Corporation (EFC). Located in Boston, the EFC is part of the vast American military build-up necessary to wage the World War. Like nearly everyone else, Sloane looks around and sees the obvious—a serious illness is spreading with the speed of a wildfire. He judges the scene, weighs it against the experience of the spring and its Wave One of influenza, and makes a clear determination—this is different.

Sloane’s not done. He goes on today to add a conclusion that carries the weight, the stature, the influence of his uniform. US Lt. Col. Sloane states that the illness is the work of the Germans, the enemy in the World War, because they’ve done such things in the past. Why stop now, Sloane asks. His rhetorical question is all the louder with the American public’s knowledge that mustard gas and other chemical agents have been used for the first time in the European war. It’s a new reality of war in the trenches. Sloane’s remark shows it’s likely a new reality of war in the homeland, too. Or at least that’s his inference.

Looking Ahead From Today, September 17, 2020

Wave Two is not Wave One. The numbers aren’t the same and neither is the look, feel, and tone. Neither is the toll and cost. All of it differs. Taking the next step in the realization of the difference is the knowledge that solutions, strategies, the things you can rely on to help you and others endure and persist will likely be different as well. Actions must be made anew.

The hardwood trees have something to teach us. The leaves grown in the spring and waving in the summer have a life. At a particular time, they brown, die, and drop. The trees live on. In the chill, the cold, the darkness, and distance of the sun, they continue. They experience autumn and winter on their own terms, not as repetitions of spring and summer.

Our Wave Two is not our Wave One. It is a new season.

For Those Wanting To Bridge 2020 And 1918, A Reminder…

Warfluenza and Warcorona.

Warfluenza is what Americans experienced in 1918 when influenza interacted with their dominant issue and concern of the day, World War One. The illness comes to them through their handling of and coping with World War One. That’s why I want you to think of it as Warfluenza. The pandemic and the issue affect each other.

Warcorona is what Americans are experienced in 2020 when coronavirus interacts with our dominant issue and concern of the day, World War Trump. Regardless of whether you love or hate Trump, Trumpism, and the Trump Presidency, it blends with the illness and thus we handle and cope with both together, inseparable. It’s Warfluenza updated to our world—Warcorona.

I want to reintroduce you to the world of Warfluenza’s Wave Two because we’re in Warcorona’s Wave Two right now. We’re following Warfluenza and Warcorona on exactly the same days across 102 years. Mark Twain is supposed to have said that history doesn’t repeat but it sure does rhyme.

Count me as a “yes” to that statement.

As always, I invite you to reach out to me. Leave a comment here, email at dan@historicalsolutions, or text at 317-407-3687.