THE THIRD MONTH – TODAY IN 1918

Week 9 (Days 59-67, Nov 5-13, 1918)

As of the first week in November, influenza barely, ever so barely, inches below its awful highest point of death and destruction in October. Then, it—or rather, they—happened. The happenings were public events, the occasion when people pushed beyond the rules and regulations made to help them stay healthy and avoid sickness. They came out of their houses and workplaces, often without protective gear, nearly always crammed close together. Just when the first hints of influenza’s decline were beginning to form, people engaged in public gatherings. It didn’t take long for more illness to spread.

The gatherings were formal and planned, informal and spontaneous. The mid-term congressional election occurred as scheduled. No one thought much about postponements or major alterations. People did receive advice on how to reduce the risks of contracting influenza while voting. A pair of other events were the election’s opposite, informal and spontaneous. A false report of the declared end of the World War sent people racing into the streets, plazas, and public squares. Just hours later, a true and accurate report repeated the flood of people. Special parades and ceremonies erupted. Hugging, kissing, crying. Pandemonium and pandemic together.

The public activity outraged health officials. They expressed frustration with people who for a time had adhered to their recommendations but now gleefully ignored them. Roughly one to two weeks ago, at Halloween, the public had followed their directions usually. That acceptance appeared to be gone. As had been true before, the death toll of influenza continued to shock people. Members of entire families died within days of each other.

Week 10 (Days 68-76, Nov 14-22, 1918)

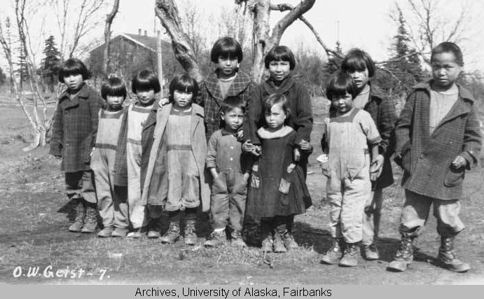

The re-ignition of influenza blasted some areas where sickness had occurred before only slightly or not at all. Pivoting sharply from healthfulness to illness, communities saw a few cases or even no cases become dozens or a hundred over night. The affliction now reached into the remotest American lands, including north of Nome, Alaska where native populations at a Christian mission were nearly wiped out, leaving more Bibles than people. Experts in public health uncovered hidden devastation in hard-to-reach locations, such as Big Stone Gap in the mountains of southwestern Virginia. Doctors, nurses, and administrators responsible were stunned to learn of people who starved to death while suffering from influenza.

With influenza roaring where silence once stood, the ability to form experiences into a story vanished. Reality lurched and rattled beyond the capacity of people to make sense of the world around them. This was a major impetus behind the ruination of life in mountain valleys as at Big Stone Gap or in sheltered villages like the Alaskan mission. The steep proportion of death within life weakened assumptions about neighborly support and the prospect of help from caring strangers. Death was everywhere while life huddled in the corners.

Week 11 (Days 78-82, Nov 23-27, 1918)

Take ’em off. Pull ’em off. Get ’em off.

At the sound of a siren city-wide, the people of San Francisco, California remove the masks from their faces.

It is an extraordinary moment of influenza. Facial masks have come to be the most powerful symbol among the alive and the living. Supporters of the masks say the items saved them from illness and death. A necessity, pure and simple. Opponents of the masks say they ripped apart the fabric of normal and daily life. An outrage, pure and simple. Regardless, both sides of this fierce debate are now in the shared, masks-no-more civic space of San Francisco. For communities who have adopted facial masks in this pandemic, every one has it’s San Francisco moment when the worst seems past and tomorrow seems like normal from a while ago.

By late November influenza is more of a surgical killer than a mass murderer. Death touches and slips away instead of exploding and flattening out. The ongoing reality of influenza as the end of November comes into sight is a double-new—influenza is new in places where it never was and influenza is renewed in some places where it used to be. To deal with influenza in late November, public health officials begin speaking sentences with the words “contact tracing” in them. People, they believe, will take comfort in knowing exactly where the restart was.

The end of the World War announced and celebrated two weeks ago has underscored the irony of influenza. As families prepared to embrace a returning son, father, brother, uncle, or friend—a return which will occur over the coming weeks and months—irony takes on its most vicious and cruel form. Those not coming back, those who are dead, were often the victims of the invisible enemy, influenza. They die not on battlefields. They die without wounds or injuries in hospitals, barracks, and quarters. They made history in their families by serving in the nation’s first overseas, multi-national war but were killed by the same force that took the life of someone in the home here or down the street.

Week 12 (Days 84-90, Nov 28-Dec 4, 1918)

The realization of the misshapen scale of events drills deeper in civic consciousness. A newspaper in Denver, Colorado draws a public comparison unthinkable weeks ago—influenza has killed more of our city residents than the World War has killed in our entire state. Out of whack.

Maps show the latest outbreaks of influenza. In Pennsylvania, California, Iowa, and Missouri influenza is a powerful presence in homes and hospitals. For them it is the first scene of a reality that had unfolded throughout the late summer and fall.

It’s the second major public and civic day of American life dominated by influenza. Thanksgiving. Halloween was the first and now here is the second. Lots had changed in a few days shy of a month. And yet, lots hadn’t changed much at all. Among the constants was the shadow of influenza cast across American tables filled with food and surrounded by chairs. Fewer chairs.

As bad as it is, a collective belief exists that a factual decline has occurred in influenza. Day to day, deaths and cases are fewer. Life regains itself with the onset of December.

The edges of shock are beginning to come into view. More than 350,000 Americans have been killed by influenza since early September, since the count of days began which now number 90. Each has a story. The writing of one of them ends today.

Edna Fletcher had devoted her life to nursing and to nursing education. She was 33 years old, single and childless but known as “Maw” everywhere at Methodist Hospital in Indianapolis, Indiana. She’s Maw because she’s everyone’s mother-like figure in her constant urging to do what’s best, to be the best you can, to strive and strive and strive to care for patients as only the world’s best nurses can. And Fletcher took all of her “Mawness” to Fort Benjamin Harrison where she and twelve volunteer student-nurses had cared for hundreds men sick with influenza and thousands of men terrified by the thought of influenza.

Back from the fort, Fletcher had her Thanksgiving in the Nurses Home in the city. That’s where—as the vicious and cruel ironic side of influenza would have it—she became sick with burning fever, severe congestion, and body-racking pain. Influenza killed Maw on the 96th hour of her illness, on the 90th day of the pandemic.

The healthcare woman who cared for sick men, the civilian in the wartime post, a person of health in a time of pandemic, a holiday meal enjoyed and a fatal illness caught, life then and death now. Opposites all.

A cemetery in Lafayette, Indiana was where Edna Fletcher did in December 1918 what Abraham Lincoln had done on Gettysburg’s Cemetery Hill in November 1863. She summed up. She found a meaning. She made lasting sense of a tragic time.

Lincoln’s effort was words spoken from a sheet of paper. Fletcher’s effort was the silence of a burial site. He talked about a nation’s rebirth through new freedom. She signaled that her grave, dug near the first place where she was a leader of nursing and nursing students, was a rebirth of who she was and was meant to be. On the 90th day, influenza declines and her story ends.

A FEW THINGS TO KEEP IN MIND AS YOU MOVE INTO THE WEEKS AND MONTHS AHEAD IN 2020

…The Warfluenza of 1918 (the World War + influenza) lives on and thrives in 2020 (Coronavirus + The Political World of Trump, Pro-Trump, and Anti-Trump + racial, social, civic unrest, and POTUS 45’s reaction to them), twisting into new directions with new dynamics…

Warfluenza has a pair of opposites. They are set dates and sudden shocks. The election in November 2020 is a fixed date. The end of the World War in 1918 unfolded in such a way that it was clear an end was in sight. The only question then was exactly when and the circumstances that would produce the when (the how). Strangely, Warfluenza in 1918 showed that the set date, the fixed thing, can still contain a surprise—look at the rumored end of November 10 and the actual end of November 11.

Even the thing you think you know for certain can startle you. Mark that.

We don’t have that question of unknown in terms of time—we know when the 2020 election will occur. It’s a fixed date. Maybe we’ll reach a stage where the outcome looks certain, too. However, if we want to learn one of the most important lessons of Warfluenza 1918 we must embrace the possibility/probability that something within the known, the fixed, the expected and pre-set will likely startle us, too.

As I mentioned, the fixed date and the sudden surprise are a pair of opposites inside Warfluenza. There are more. Rather than list them, though, let’s ask ourselves more questions about opposite pairings as a construct. I suggest it because while opposite pairings are likely part of life (as well as the past and history) whatever the circumstance, it feels to me that they are a telling feature of Warfluenza.

A few to consider:

- Do I have an instinctive reaction to paired opposites?

- In going further than my instinct, what do I tend to lean on in understanding and dealing with paired opposites?

- Am I confident in my ability to turn to my followers and with them tackle the challenge of paired opposites?

…A shared experience is not an equal experience…

Communities hardest hit in earlier phases of Warfluenza frequently did not experience the condition in the same way as communities which, in late November and early December, faced it for the first time. Actions taken 30 or 60 days ago were tired and worn in the minds of people as the 70th and 80th and 90th day approached. By the latter period, those who now needed these actions would cope with the added problem of fatigue and restlessness within other publics whose support they might require. It was another obstacle to overcome.

The inequality of sharedness reflected the range of inequities already existing in the communities. Such a range included age, geographic location, race, economics, family cohesion, gender, to name a few in the gallery of the human condition. Disadvantages on the ground made influenza even deadlier and more difficult when it struck.

Further than these was the pressure of time and time’s passage when looked across a broader landscape of multiple communities. No one endures forever without change, and wherever and whenever a person emerges from sickness along the timeline of Warfluenza, they will react to those newer to the reality they have already known for part of their lives. Time and time’s passage will only magnify the pressures between veteran and newcomer. To say that, yes, I had the same illness some months ago when my community dealt with it was not the same thing as saying yes, I am among the first to have influenza in my community now. The bonds among us are worn, weathered, and weakened.

The inequality of sharedness will strike at some of our worst features of Warfluenza. It is quickly weaponized, deployed, and detonated. You will constantly be called into the fray, to find the nearest rock and refashion it into a bomb. The rock-to-bomb cycle will be driven by a shortening of time (immediate demands of and expectations for responses to events and rumored events) and an overabundance of particles posing as data and information (comparable to sands on the beach). You will be tested for your steadiness, rootedness, and maturity. But don’t assume that if you resist the rock-to-bomb cycle you will be left alone. You will not be. You will be confronted again.

…Be it a dip or a decline, the slope goes down in either case…

The statistics of influenza were once up and now they’re down, they’re lower. However sliced, lesser means fewer, not as much, and not as bad. Not as many deaths or cases and far easier to return to the routines of life. That’s what everyone wants. The sticking point is that in the moment—at that point on the horizontal graph where the future begins, hard up against the right-hand wall and right-side margin—you really can’t tell if down stops and goes up (defining a temporary dip) or down continues going down (pointing to a lasting and new condition).

Warfluenza will be at its most confounding in the slide of the slope. Arguments, bad faith, the unearthing of earlier mistakes or missteps, all of it will fly through the air as people attempt to decide how to connect past, present, and future while on the slope. The resources most scarce in supply will be trust, allowances, and the benefit of the doubt. Lacking them, or finding them poisoned in storage or moth-eaten on the shelf, people will be left to finding a point of exhaustion, of distraction, of withdrawal.

Those who can and are so inclined will seek a meaning and a passage. The meaning will be a blend of revived purpose and restored effort. The suffering of months past will serve such an end. With meaning found, a route forward can be charted with clarity and spirit. Not every step or even most steps will be marked out, but the direction of passage will be evident all the same. These people are the truly fortunate and it will pay to be one or know one.

As for me, I will return. My reappearance will follow a pause drawn from the past, from the paired opposites of 1918-1919, the year of war and the year of peace bridged by the story of illness and its collision with the great issues of American days and nights. I will then invite you to walk the bridge again from a season of 2020 back to the past, to the next wave of Warfluenza.