A siren has a sound all its own. It fills, pierces, and overwhelms all at once. The sound enters your ears and holds in place beside your brain. Open your mouth and it will enter there, too. Your nose is next.

Hear it?

A siren cannot be escaped until the sound starts its steady winding-down. Less. Fading. Stopped. Silent.

Now what?

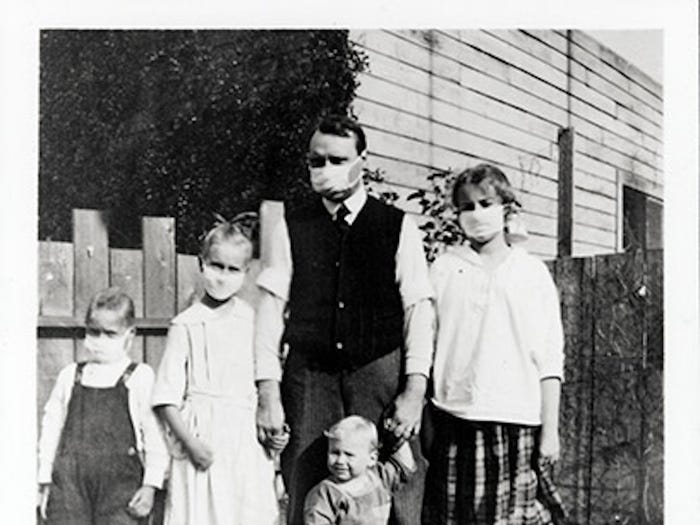

The people of San Francisco know exactly what. Exactly. At noon today, Day 77 since the Fort Devens outbreak of influenza, November 21, 1918, the siren blasts and screams and wails. Either a minute or a lifetime later, all San Franciscans raise their hands, grasp the edges with their fingers, and—rip, tear, jerk, yank, pull…off the masks from noses and mouths and faces! Free again! Free at last! We! You! Me! No more mask!

Throughout the city, members of the local Anti-Mask League swoon in near ecstasy. They’ve urged and argued and demanded. Finally, it’s here for one and all, once and forever. No more masks! And the masks are only the symbolic beginning—the full life of the city is open again today as well.

The city’s police chief of police, David White, is busy seeking payments today from recent violators of the must-wear-mask rule. Among them are local politicians, insiders, and more than a few shady characters. White is respected and popular, one of the first of his rank and position in the nation to hire female police officers. So now, his public reputation gives him the room to call for the fines to be paid. As the celebration roars ahead, White tells newspaper reporters that he expects the payments.

Hildreth Heiney is a schoolteacher in Indianapolis, Indiana. She’s writing a letter to her fiance, Kleber Hadley, in the US military, the 336th Infantry. She knows the tedium of mask-wearing. She’s been wearing one. She decided a while ago to find the fun in it, looking for unusual masks. Some of the masks she’s seen, she informs him, are thick, some are thin, some colorful, some artistic. She especially notices a mask with cats sketched along the edges. “O this is a great old world. And one should surely have a sense of humor,” she writes. Good advice, good way to live. Whether as a fiance or students, it’s nice to know people like her. She’ll change lives in either instance.

Influenza isn’t the mass murderer it once was. A surgical killer in multiple places is now its style. In Pennsylvania the people of Philadelphia try to piece life back together. The extent of cases and deaths are down again but the discovery of new poverty in homes destroyed by the illness continues to increase. “Flare-ups” of influenza are seen today in the smaller towns of the central and western parts of the state. Asheville, North Carolina’s newspaper, The Citizen, reports that influenza is diminishing in the city but deepening in the countryside. “Conditions in the townships are now worse than at any time since the epidemic started,” a reporter states. Boston has 36 new cases today—not a conflagration as before but a sharp rise over recent days—with the city’s health commissioner pinpointing, through “tracing” as he terms it, the new spread coming from Boston Elevated train cars. The health commissioner emphasizes a specific location and smallish numbers. Influenza adapts. The health commissioner reassures. Life goes on.

Things are hard in Nebraska today. In Aurora, three funerals occur for the same family. All of them are victims of influenza. In a small prairie town, the loss resembles a device going off, though not a siren, more like a bomb.

A few hours north of Aurora, in David City, Nebraska, a man learns that his brother-in-law, Hal Brockett, is in serious trouble. Brockett is in the US Army and had gotten influenza while in training in Lincoln, Nebraska. Brockett survived, recovered, and traveled east to Fort McHenry in Baltimore to continue military service. Like many parts of the United States, influenza had returned a few days ago, strangely timed with the Armistice Day celebrations. Brockett was now badly sick again and, worse, the reappearance of the illness had pushed him into a nervous breakdown. He was in the camp hospital once more, physically and mentally broken.

Maybe Brockett can make it back to Nebraska. Maybe he can’t. Maybe he’ll walk in and get backslaps and shouts of “great to see you!”, “glad you’re better!”, and “we love you, Hal!” to welcome him home. Or maybe he’ll lie flat and get a salute and “Taps” rising from the metal of a single horn. Maybe, through the tears, they’ll whisper “we love you, Hal” as a final goodbye.

You’ll know when you hear the sounds.

A thought for you on Day 77, May 27, 2020, seventy-seven days after President Trump declares Covid-19 a national emergency—two things. First, people can cluster in two groups. Probably at least two groups. For my purposes, let’s stick with two. One of them is of folks who do what’s asked and look for a way to make it work as best they can. The other of them drive hard from either end, going all-out yes or all-out no and having next to no patience with everyone else not in their camp. You get some of the feeling of the two groups when you look at the Anti-Mask League of San Francisco and the schoolteacher in Indianapolis. The league members and the teacher approach influenza in very different ways. And second, navigating change and continuity is always a challenge but in times like influenza and Covid-19, the challenges reach ballistic proportions. I’ve said this before; it’s nothing new. But what’s ballistic about it at this point in time? Late November 1918 helps answer the question: change changes and continuity continues, doing so while splitting, multiplying, and vibrating like hypercharged cells. Each lunges and careens along paths that plummet and climb. The only thing they might share is time’s existence and time’s passage. Thus, ballistic challenges are these: the pairing of divergent human action and conduct within environments of unstable gravity. The wisest course for you to take as a leader is to know that both things—the first and second thing—are alive and affecting tomorrow. You’ll spend your time with the conduct of people by necessity, either making-do or going all-out. But people are not solo actors floating in air. They have a stage, a backdrop, a background, and vastly more that comprises an environment. This environment is a drama of its own, where change and continuity and the legions within them affect the outcome, too, and in ways larger than we assume, larger than we’re used to knowing.

(note to reader—I invite you to subscribe to this series/blog. The purpose of my posting in this series is the purpose of my enterprise at Historical Solutions—to explore the past in a new way that brings new and different value to you, both in the present (this minute) and on the edge of the future (what’s ahead or forward of this minute). The past is everything before now, the totality of all time before the present; history is a set of very small slices of the past that, for a particular reason, have been remembered. If you wish to contact me privately, please do not hesitate to text or call 317-407-3687)