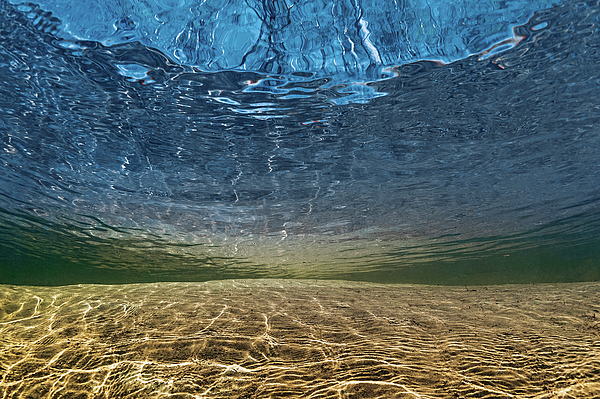

A river has a surface. That is its highest level. A river also has a bottom. The surface water runs along it, above it, over it. The water at the top and the water at the bottom are almost two different worlds.

One man rides the river’s surface. In the darkness below two families struggle along the river’s bottom. This is a Day 59 like no other.

The 59th Day since influenza’s outbreak at Fort Devens, Massachusetts is one that many Americans, pandemic or not, have looked forward to for a long time. It is Election Day, 1918. November 5. Today is a known marker in the flow of American political life—the mid-term elections.

In Congress, every member of the House of Representatives is up for election. One-third of the membership of the Senate is up for election. In the 48 states governors, state legislators, and scads and scads of city, county, and township offices have their elections today, too.

The polling places throughout the United States have restrictions unprecedented in the American experience. In many communities voters must wear their flu masks in order to vote. They must be aware not to stand too closely together, not to spit or cough or touch needlessly. If they feel unwell, they must make a responsible decision about whether to show up at all to vote.

Influenza affects actual voting as much as preparation for voting. Turnout across the states is low, approximately 20% lower than is usual for a mid-term election.

Voter turnout is bad luck for President Woodrow Wilson. He’d staked a lot on this election. Ten days ago, he declared publicly that with the World War likely coming soon to a victorious conclusion, his primary war goal of starting a global “League of Nations” was at stake. He needed Democrats—and only Democrats—to win in Congress. Low turnout hurt Wilson’s chances at reaching his goal.

Voter results sealed the case. Wilson’s Democratic Party lost 24 seats in the House of Representatives and 6 seats in the Senate; 4 governorships were also lost. Worse yet for Wilson, the Republican Party, his opponents, took control of both the House and the Senate, a problem for the President who wanted to seek enactment of his history-making “League of Nations” concept. Wilson needed Congress to vote for the League. He couldn’t mandate it on his own. The task to secure approval was now drastically more complicated. Thanks to the disruptiveness of influenza.

On the surface, the river was now choppy, swirling, and rough.

So much for Wilson’s Day 59.

Lower down, at the bottom of the river, the surface seems irrelevant. Two families, one in Pennsylvania and one in Colorado, are in the deep and dark waters.

Charles Hausele Sr lives in Pleasant Unity, Pennsylvania, a perfectly named place if ever one existed. He lives there with his wife and eight children. One of his sons is married and has a child, Charles’s only grandchild thus far.

In something less than six days, influenza descends on the Hausele home. Five of Charles’s children die. His wife dies. His daughter-in-law dies. His grandchild dies. Some of the deaths are only a half-hour apart. Only two sons survive. Another son’s condition is unknown. He’s in France in the American military. Charles’s family is in shreds. Pleasant Unity is gone forever.

Florence Phye lives in Loveland, Colorado. The Phye family of two parents and six children have been in the Elks Lodge dining-room-converted-to-hospital-ward in Loveland. Florence also has a husband and a three-year old son, Charlie, from a previous marriage.

Following the same timeline as Charles’s family in Pennsylvania, the eight Phyes die one by one in less than a week at the Elks Lodge. The only survivor is little Charlie and his step-father. The stonemason mispelled the family’s last name on the cemetery marker. “Phies” was the mistake.

Two families, dying or dead, all of them or nearly so. At the core of conscious earthly existence—the people of birth and life, of living, of being a human being—an invisible and outside force has entered, spread, and soaked them in death.

Hundreds and hundreds of families are like the Phyes and the Hauseles. Nothing pleasant in Pleasant Unity and no love in Loveland.

Days ago it was a cough, congestion, discomfort. From this minute forward, nothing can be done. Nothing is available. A few words with sounds spoken and heard. They are meant to share in seconds the depth of a life and its most defining emotions. People who together laughed, cried, dreamed, feared, hoped, raged, kissed, hugged, slapped, and touched. Only a look is left.

The passage of an hour, of minutes, is the span when the body loses another life-force, in the lungs, the throat, the muscles and skeleton. Aches, pain, fever emanate to the edges of the skin. Consciousness and sentience disappear. A final moment, the last breath, and then absence, emptiness, vanquishment. Name by name, before oldness and wornness, they perish. A memory begins and, like the life just lost, slowly turns along the bottom.

Whole families under white sheets. Carried out and driven away.

Someone knows their names. Someone speaks about them. Someone in the deep.

A thought for you on Day 59, May 10, 2020, fifty-nine days after President Trump declares Covid-19 a national emergency—whole families. It’s said that in outer space black holes consume all light, all matter and material. Here on earth, when death consumes a family, a black hole opens up. A loss beyond language is the only reality left behind. Perhaps Covid-19’s most unnerving element is that it strikes through and into entire families. The family and its space—the home—have been the next-to-final place of retreat in the struggle against the illness; the hospital bed is the only remaining destination. Ever smaller, ever more tightly drawn and framed and numbered, the family is the last patch of person and ground in the fight for regaining daily living. The bottom of a river produces the rapids, ripples, and obstructions on the top. You will begin here, in the bottom of the river, where the grade falls and where the gravel and mud hold up the rocks and dead trees, to shape the flow and pace of the water’s surface. What you’re able to do on the bottom will affect where you’re able to roll and flow for years to come. Do the work on the river bottom.

(note to reader—I invite you to subscribe to this series/blog. The purpose of my posting in this series is the purpose of my enterprise at Historical Solutions—to explore the past in a new way that brings new and different value to you, both in the present (this minute) and on the edge of the future (what’s ahead or forward of this minute). The past is everything before now, the totality of all time before the present; history is a set of very small slices of the past that, for a particular reason, have been remembered. If you wish to contact me privately, please do not hesitate to text or call 317-407-3687)