Through the gray cloud of influenza a flash of light is seen on October 22, 1918, Day 45 of the pandemic.

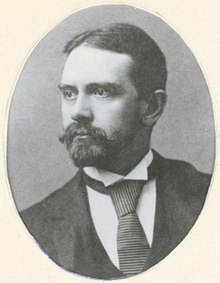

Dr. Edward Rosenow is 43 years old and has for some time been regarded as brilliant in his field of medical research, a producer of “monumental work” as one person put it. A few weeks before influenza’s outbreak at Fort Devens, Massachusetts, Dr. Rosenow was a featured presenter and analyst at the Minnesota State Medical Association meeting. Today, at the Mayo Foundation for Medical Examination and Research in Rochester, Dr. Rosenow announces he is ready to distribute a vaccine for doctors to take. Three shots, each a week apart, for six to nine months and it’s expected, Dr. Rosenow states, that they will have immunity to influenza. It a rare step ahead when all anyone seems to do is fall further behind.

While the Minnesota medical profession celebrates Rosenow’s achievement, influenza chops down one stand of normalcy after another. Nationally, a ban on “fancy coffins” is declared. Judge Edwin Parker, Priorities Commisioner on the War Industries Board, dictates that only plain, sparse coffins may be made. To do otherwise, Parker explains, risks failure to meet the demand of corpses caused by influenza. At Cornell University students begin a week of in-room study; assignments will be completed in individual dorm rooms instead of classrooms. A newspaper editor in Santa Cruz, California suggests that influenza depends on travel to thrive and thus perhaps people should stay in their home counties.

The Masonic Lodge of Asheville, North Carolina meets and decides to that decades-old racial discrimination must be addressed in the struggle with influenza. Weeks before, a whites-only emergency hospital had opened to care for the rising numbers of influenza cases in the community. No one—not a single entity—had bothered to look at options available to black residents of Asheville until the Masons voted to put their “Temple” at the disposal of doctors treating black patients with influenza. Not all the timber cut down by influenza was bad.

The University of California begins a quarantine of all members of the Student Army Training Corps on campus. In addition, Professor of English and classical literature, Charles Gayley, cancels his planned lecture on “The Ideals of the Present War.” It seems the good professor, who was born on the birthday of George Washington, is a target for the other enemy in a different war—influenza.

Which brings a new context to the day. Influenza is killing more Americans in a few months of 1918 than did most of the American wars combined in the nation’s previous 143 years of existence.

In reality, this war and its battles are felt in every American home.

A thought for you on Day 45, April 26, 2020, forty-five days after President Trump declares Covid-19 a national emergency—the cancelled lecture. To a person, Americans who supported and waged the World War would tell you that they were fighting for one ideology and against another. They might have referred to it as a particular “way of life.” Professor Gayley was a widely-known public speaker who promoted and defended the war. His planned speech was an effort to define and organize the ideas served by the war which, in terms of deaths and locations of deaths, was already far less severe and jolting than influenza. Given influenza’s much greater effectiveness in uprooting and overturning daily life—hounding normalcy like a wolfpack chases its prey—it’s certainly possible that the depth of change will also produce a change of ideology? When things that are so fundamental are altered and reconfigured, the chances grow that, with them, related ideas, assumptions, and articles of faith may be equally altered and reconfigured as well. The Asheville Masons were acting on precisely this level. They reoriented some of the basic principles of local life because the combination of influenza and humanity demanded it. Not everyone agreed and the Masons didn’t go to the fullest extent of their changes. Nevertheless, a change occurs in the ways of living, of thinking, of believing. The good professor might have written the right speech for the wrong war. Can you feel your ideas changing?

(note to reader—I invite you to subscribe to this series/blog. The purpose of my posting in this series is the purpose of my enterprise at Historical Solutions—to explore the past in a new way that brings new and different value to you, both in the present (this minute) and on the edge of the future (what’s ahead or forward of this minute). The past is everything before now, the totality of all time before the present; history is a set of very small slices of the past that, for a particular reason, have been remembered. If you wish to contact me privately, please do not hesitate to text or call 317-407-3687)