All sorts of horse races were up in the air on the forty-third day since hell bolted free at Fort Devens, Massachusetts.

There was the natural kind. The horses expected to run at Pimlico Race Track near Baltimore, Maryland were still in their stalls. Race officials in Maryland and at Pimlico were going back-and-forth about holding races. For now, they had decided to take a week off from racing while influenza burned across the land. Their decision put them in the middle between other competing centers of the sport. New York—which had 500,000 cases of influenza, according to one newspaper—was still racing at the Jamaica track. Several thousand people were regular attenders. Kentucky had taken a sterner approach, having postponed races earlier on at Churchill Downs. Fixed nervously in between with its indecisiveness, Maryland had the horse partly in and partly out of the barn. The middle can be frustrating.

There was the louder kind of horse racing, too. Political elections. An election would be occurring throughout the United States in less than three weeks. All of the House of Representatives, some of the Senate, state offices, local offices, thousands of candidates would be running for hundreds of elected positions. Of course, there is the candidate with no party, no fundraising, no political organization but which is dominating every political horse-race: influenza.

In Chicago, to cite one of many examples, political observers notice that candidates only had publicity and personal organizations to do the campaigning. The usual parade of celebrities, speakers, hawkers, and hacks aren’t around. In a season where fevered pitches were meant for election rallies, influenza is winning.

Normal life couldn’t gain a foothold.

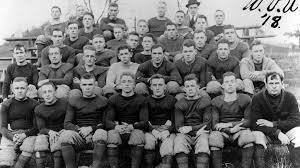

The West Virginia University football team was supposed to be in the middle of a fantastic season. Supposed to be. Not any longer. The games are postponed indefinitely. Offensive lineman Joseph Fuccy had gone to his home sixty miles away in Weston. Disappointed, he caught a cold. Only a few days later, he dies, and today his family plans for the funeral. A newspaper writer urges readers not to cast blame on anyone for either the player’s death or the schedule’s delay. “Every consideration,” asserts the writer, “must be subordinated to the war and its prosecution.”

Pennsylvania offers the smallest glimpse of normal life today. “Automobiling” will be allowed. With more than 10,000 dead from influenza, however, no one gets in their cars for a pleasure drive. A Mennonite farmer thinks everyone is either sick or somehow involved in the war and thus not interested in this wildly popular pastime.

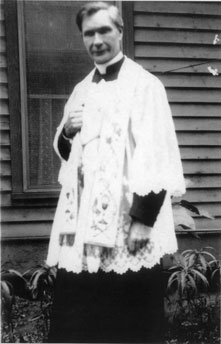

A Catholic priest in Birmingham, Alabama writes a special letter to his parishioners. He knows that not having Mass will be disorienting to them; it’s the first time the worship service won’t be offered to them locally. Influenza. Father James Coyle begins his letter this way: “A situation unprecedented in the history of our State presents itself to you today.” It’s a remarkable start to a letter written for a place that spilled blood in the Civil War, scarred and burned the skin of the left-over Civil War, and had coped with countless illnesses, sicknesses, and life-shortening diseases. No, Father said, now is “a situation unprecedented.”

A few people stare out into the frigid waters off Nome, Alaska. A ship is on the horizon, a normal thing. Aboard today is influenza and soon normal is the precedent fast forgotten.

A thought for you on Day 43, April 24, 2020, forty-three days after President Trump declares Covid-19 a national emergency—words of the Father. I didn’t hear the Birmingham Father’s words. I read them, as he intended. Yet I could also hear a voice saying them aloud. After he opened with the quote above, he wrote a description of what Mass meant to people of the Catholic faith, how it sustains and thrills with mystery and shadow. But it was 1918’s influenza that, to him, was the break in the chain, the starkly different experience apart from everything eternal. He is convinced of this as fact and I suspect millions of Americans agree with him. Now, I want you to take Father’s words and lay them alongside the remarks made when the UWV football player dies. Here, in sharpest fashion, is a second viewpoint we’ve seen a lot—that the World War is the single most important issue of the day, pushing everything else into the background. Millions of Americans agree with this, too. So, what do you make of these two thoughts together? What does it mean for them to be shared by most of the American people? How does their interaction affect American life unfolding day-to-day? And if I ask you to think of the two most powerfully shared ideas today, among 2020 Americans, what comes to your mind? How do you two ideas sit beside each other today? And most importantly of all, how do they interact and affect you, me, us, as the days unfold?

(note to reader—I invite you to subscribe to this series/blog. The purpose of my posting in this series is the purpose of my enterprise at Historical Solutions—to explore the past in a new way that brings new and different value to you, both in the present (this minute) and on the edge of the future (what’s ahead or forward of this minute). The past is everything before now, the totality of all time before the present; history is a set of very small slices of the past that, for a particular reason, have been remembered. If you wish to contact me privately, please do not hesitate to text or call 317-407-3687)