In their locations, they were a half-mile apart at most. In their hierarchies of work, they were a universe apart at least. Nonetheless, on the 41st day since influenza began to rip apart Fort Devens, Massachusetts, they were joined in a life of pandemic whether they knew it or not.

October 18, 1918.

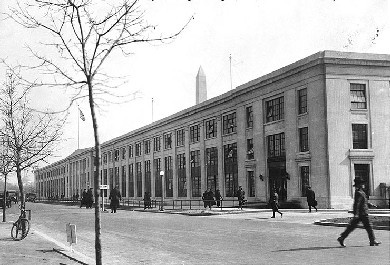

The Native American typist named Lutiant Van Wert or Luciant La Voye ends another week of work at the Interior Department within sight of the Washington Monument. There are the mundane tasks at work, like collecting bids from furniture contractors. Good news circulates within the Interior building about city residents fulfilling the fourth-round quota of Liberty Loan purchases. Good news also mingles with bad: a co-worker’s son is buried, a victim of influenza. The sickness kills 84 other people in the city this day. A new problem appears—what to do with all the children who are now orphans. No word yet about whether she’ll be a volunteer nurse again for the Red Cross. The letter Lutiant/Luciant typed yesterday about her experiences as a temporary nurse now travels in a train one day west toward Kansas. So ends another day at her tip of the Executive Branch.

Up the tree, down the tree, or wherever you locate the big boss on the tree, President Woodrow Wilson sits atop the hierarchy of the United States Government’s Executive Branch. He is at the White House, only a short distance away from the Typist’s desk. Both the President and the Typist belong to a federal governmental bureaucracy growing at weed-like speed in these days of war.

Unlike the Typist, though, the President had done next to nothing in responding to influenza by Day 41.

Wilson had listened to his wife, Edith, when she approached him with an idea. She wanted to boost morale among women working in the war effort who were sick with influenza. She believed they would be uplifted if each received a white rose from the White House. Her husband, the President, nodded his agreement and a single white rose was delivered to 1000 homes and apartments across Washington DC.

Wilson had coped with the absence of his secretary who had been out sick with influenza. He was falling behind in answering correspondence from important visitors and allies in domestic politics. Normally meticulous in communication, the delays frustrated Wilson.

Wilson had listened to recommendations from doctors and advisors that he stop attending church in Washington DC until the influenza crisis passed. Like most local people, Wilson heeded the advice and was staying home on Sundays. He missed church.

Most of all, though, Wilson had begun to hear other influenza-related counsel that pertained to the one topic of constant priority to him—the World War. There wasn’t an aspect of the war that didn’t matter to him. Production, labor, strategy, morale, diplomacy, equipment, soldiers, and on and on, Wilson wanted to know everything and, in many cases, decide everything he regarded as vital.

He had come to understand that the pervasiveness of influenza was hurting the American war effort and not just with workers, as his wife’s 1000-rose gesture had addressed. Wilson heard report after report that American soldiers were sick and dying, both in France and in transport ships headed to France. Combined with the blatantly obvious reality of influenza all around him, Wilson decided to touch on the issue with the military commander immediately in charge of the war itself—General Peyton March.

Wilson met March to discuss influenza. Tip-toeing into the topic, Wilson said, “General March, I have had representations sent to me by men whose ability and patriotism are unquestioned that I should stop the shipment of men to France until the epidemic of influenza is under control.”

Wilson’s wording said as much as his words.

His starting point was to assume such a recommendation would include the worst assumptions of the people involved. Anything said or thought that didn’t meet an all-out, full-throttle pursuit of warmaking had to be, in its origin, a sign of inability and lack of patriotism. Wilson was barely a half-step shy of saying such people were stupid and traitorous. This outlook of Wilson’s was almost as lethal as influenza itself, killing off nearly all open discussion and debate.

In addition, Wilson’s language hinted at a round-about path of communication. He, a former college president and professor who prized his ability with words, referenced “representations” that had been “sent..by men….” The feel was one of circumventing formal channels, the hard-and-fast chain of command that defined March’s world and which was, in Wilson’s view, engaged in a World War of national and global life-and-death consequence. It was, after all, “the war to end all wars.” The nature of Wilson’s wording effectively undercut the substance of the words themselves.

March seized the moment. He quickly described all the precautions taken to limit the reach of influenza in the military’s ranks. Having dispensed of fears that the US military had done nothing, March went on to press the point of larger stakes. He predicted the “psychological effect it would have on a weakening enemy to learn that the American divisions and replacements were no longer arriving” because of influenza. Finally, and most chillingly, March assured Wilson that “every such soldier who has died (of influenza) just as surely played his part as his comrade who died in France.” Offering death as the common bond, March helped Wilson justify doing nothing about influenza as simply another bold war-time decision at the top of the Executive Branch.

Day 41 and the Typist waits for the Red Cross to call. Day 41 and the President of the United States waits for victory to call. One had a clear path of action. The other was aided in pretending to find a similar path.

A thought for you on Day 41, April 22, 2020, forty-one days after President Trump declares Covid-19 a national emergency—POTUS 28. To my knowledge, no one has found a public reference by President Woodrow Wilson that pertained to influenza. You can understand why when you look at his wording in the meeting with March. Clearly, he equated even the faintest traces of doubt or disagreement about the American role in the World War with the prevention or obstruction of victory. To him, dissent was danger, betrayal, and active support of the enemy. The World War always outweighed influenza as the fundamental American issue in the mind of Wilson during fall 1918. It was never a question of balance, dual purposes, or multiple priorities. We can look at Wilson’s conduct and come to a fast, easy conclusion—he made a horrible mistake. But we can also look at Wilson’s example and try to stretch our understanding to involve more creative thinking. We can’t substitute one single-track focus for another. We can profit fully from Wilson’s experience by knowing that the hardest thing is often the best thing—that on more occasions than we care to admit, we need to keep multiple points in mind. For us, the personal and community health aspects of Covid-19 are understandably vital. No question about it. In addition, however, we may arrive at a moment when more than one issue, goal, and priority has to be kept at the forefront. As a leader, in your vision, mind, and frame of action, make ready to make room. Two priorities can be pursued.

(note to reader—I invite you to subscribe to this series/blog. The purpose of my posting in this series is the purpose of my enterprise at Historical Solutions—to explore the past in a new way that brings new and different value to you, both in the present (this minute) and on the edge of the future (what’s ahead or forward of this minute). The past is everything before now, the totality of all time before the present; history is a set of very small slices of the past that, for a particular reason, have been remembered. If you wish to contact me privately, please do not hesitate to text or call 317-407-3687)