In New York City, on the 39th day since the outbreak at Fort Devens, Massachusetts, begins October 16, 1918.

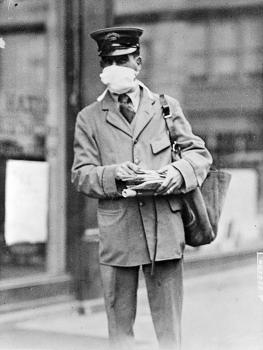

A mail carrier walks down the street with a mask on his face. An office worker sits at her desk, typing a letter and wearing a mask on her face. Across the city, if the reports are accurate, more than 400 people die today of influenza or a related illness. And the hard work of a gray-haired man vanishes into thin air.

He is Charles Sink, executive director of the University Music Society in Ann Arbor, Michigan on the campus of the University of Michigan. It was in New York City that Sink months ago had first encountered one of the world’s most famous singers, Enrico Caruso. The two had talked and after gentle urging, Caruso had agreed to include Ann Arbor in the Midwestern portion of his planned American tour of performances. Sink and Caruso’s manager had then pounded out the fee Sink would pay to Caruso: $220,000 (US dollars in 2020). Heart-stopping as the amount was—and Sink would have to scramble to raise the money—the fact of having Caruso perform at U of M would be a major cultural achievement for the school in the “Intercollegiate Conference of Faculty Representatives,” or Big-Ten for short.

But today, Sink’s heart hasn’t stopped. It’s just broken. That’s how he feels as he writes out a telegram to be sent to Caruso’s manager in New York City. Officials in Ann Arbor have closed all public events. The planned Caruso concert is dead, though Sink hopes to reschedule. Who knows if he’ll succeed? That combination of hard work and good luck way back in New York City. Perhaps—all for naught. Heart-breaking.

Another university reacts to influenza today. Brigham Young University is closed, indefinitely.

The death tolls are down in Boston. With 71 dying today, it’s the lowest total in the city for the past 23 days.

The Red Cross calls out for women. They seek the “healthy” woman who, in their view, has “double-duty” to perform, one for women fallen ill who need her help, and one for herself, knowing she is doing everything she can.

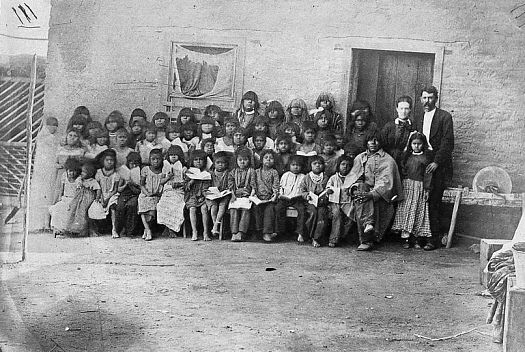

Influenza continues to respect no one. A member of Congress from St. Louis, Missouri, Jacob Meeker dies at age 40. Only six days before he had visited soldiers at Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis. It’s a good guess he got influenza there. Private Winifred Harrold dies at Wilbur Wright Air Field near Dayton, Ohio. And Lucy Antone, age 6, falls ill at Sacaton, Arizona. A member of the Akimel O’odam, or Pima, tribe, Lucy attends the St. Johns Mission school.

In the future, not far from the Antone home, a baby boy named Ira Hayes will be born who, one day, will grow up to fight in the World War gone plural, to number II, and will hold up an American flag on a small island called Iwo Jima. And in the future of the Antone family there will one day be a woman who is a master basketmaker and a respected tribal elder, and then a younger woman who wins a beauty contest and plans to enter college to be a master chef.

For now, though, it’s little Lucy with influenza that verges on pneumonia, coughing and shivering in the dry valley of the Gila River.

A thought for you on Day 39, April 20, 2020, thirty-nine days after President Trump declares Covid-19 a national emergency—the future. What does it look like? Amid the tragedy of an earthly future ending for the victims, another future awaits for their loved ones and the rest of the survivors. The future is a day for those in the masks doing a day’s work in New York City. The future is in delay, trying to rescue and recover a long-planned event in Ann Arbor. The future is whether there is improvement in decline, like what’s happening in Boston. The future is Lucy, battling to endure and opening a door for lives not yet even born. The future has many profiles. Length, range, direction, all of it can differ from person to person, place to place. The nature of today will certainly shape the future. But that’s all it does—shape. It doesn’t determine or define. It is the next step after the first step, which was today’s step. What’s not happened yet in the next step is you. You’re the only thing missing. You, and everything else that can be detected in the imprint you’re about to make. It will show a tracing of weight in the impression about to be made. The unknown is the extent of the burden borne in the weight. Can you appeal to someone to help carry the load?

(note to reader—I invite you to subscribe to this series/blog. The purpose of my posting in this series is the purpose of my enterprise at Historical Solutions—to explore the past in a new way that brings new and different value to you, both in the present (this minute) and on the edge of the future (what’s ahead or forward of this minute). The past is everything before now, the totality of all time before the present; history is a set of very small slices of the past that, for a particular reason, have been remembered. If you wish to contact me privately, please do not hesitate to text or call 317-407-3687)