High above the prairie, storm clouds fly in the night. Blown by air unusually warm for the second week of October, dark forms race through the sky. Rain is in the black air. It is a witching hour, well before the tilt and turn of the earth brings another dawn.

On the prairie is a camp. Hundreds of buildings are silent and dark. Barns, barracks, quarters, and storehouses, not a person stirs inside them. They sleep. Horses and mules sleep, too. Railroad cars and motorized trucks sit quiet. The streets and roads, set at right angles, are empty. Rising above the rooftops is a water tower, gray and metallic. The wind passes through this tall, lifeless guard of the camp. A whistling sound on the prairie.

In a building,

In a room,

In a bed,

lays a man.

For the last month, night after night, he seeks sleep. None comes. Night after night, he tries to drive away the thoughts and sights meant to torment him. He fails a little more each night. Night after night, he waits for the dawn.

Now, in this blackness, under angry clouds, he knows the dawn won’t come.

For almost thirty years he has served, he has done his duty to the point of respect and distinction. First it was the Spanish-American War, then a stint in Petrograd, Russia, next as chief of staff in the Canal Zone of Panama, and on to a solid record as an instructor at West Point, where he had graduated nearly three decades before. He is meticulous and detailed, a gifted artist, has a swift and organized mind, and proves reliable and dependable in the toughest of spots.

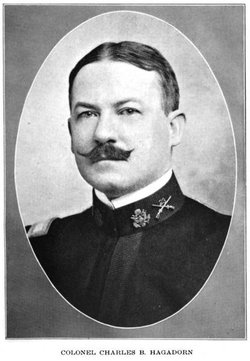

And then came the prairie. A month ago, his arrival here at the camp. In command of a place populated by more than 40,000 soldiers. Camp Grant, Illinois. Colonel Charles Baldwin Hagadorn.

Unmarried. He’s married to the Army. Childless. His children are the men he trains and instructs and sends off to the World War. So, in that way, he’s a father and husband.

In anguish. Because he can’t change the bad and make it better. They need him to help but all he can do is care.

The thousands suffering from influenza at Camp Grant. He can’t help them. The hundreds dying from influenza at Camp Grant. He can’t help them. The dead, the corpses, stacked and waiting in such numbers that the undertakers can’t cart them off fast enough.

And not a single one of them ever saw a battlefield. Killed by an invisible enemy that newly promoted Colonel Hagadorn can’t lift a finger to stop or prevent.

A month and the waiting dead pile higher on tables, wooden planks, on the floors. When will it end?

Colonel Charles Baldwin Hagadorn lays in his bed. A clock shows 3:45am. He sees an answer—it won’t end, it won’t stop, it might be another day but it won’t be a new dawn.

A few minutes tick off the clock. Soon, reveille will sound.

3:59am

Hagadorn reaches toward a night table at the side of his bed. His hand grabs a familiar item—it’s his .44-caliber Colt revolver. His fingers form around the metal.

Outside, the water tower keeps its vigil above the camp and below the clouds.

4:00am

Near the quarters of Camp Grant’s commanding officer, the firing of a shot can be heard.

By 7am he is found. Slumped on the bed, blood on the pillow, blankets, and walls. The report will say that Colonel Charles B. Hagadorn committed suicide. The reality is that he is assassinated, self-inflicted. Though it never pulls the trigger, the assassin is influenza.

One person on the prairie, the 31st day, October 8, 1918.

A thought for you on Day 31, April 12, 2020, thirty-one days after President Trump declares Covid-19 a national emergency—a life undone. Hagadorn’s entire life crumbled in the thirty days at Camp Grant. None of his excellent record mattered to him in the end. None of the hundreds and thousands of people touched directly or indirectly by his work succeeded in showing him the worth of himself. Influenza’s endlessness overcame all of that. At least that’s what Hagadorn saw when he looked into his mind’s eye and saw the scenes of the last thirty days. I hope you’re able to look beyond the recent past. You’ve done so much for so many in your time thus far. Each person you’ve served would want you to know that. All of them would implore you to understand just how much you were able to help. They will say that a legion of others, much like them, await you in the future. They will tell you the story of why endlessness is an illusion. As I write this, on today of all days, dawn returns after the long night.

(note to reader—I invite you to subscribe to this series/blog. The purpose of my posting in this series is the purpose of my enterprise at Historical Solutions—to explore the past in a new way that brings new and different value to you, both in the present (this minute) and on the edge of the future (what’s ahead or forward of this minute). The past is everything before now, the totality of all time before the present; history is a set of very small slices of the past that, for a particular reason, have been remembered. If you wish to contact me privately, please do not hesitate to text or call 317-407-3687)