Life never stops, not in its variety or surprises or challenges.

Today, Day 27, October 4, 1918, the earth shudders around the town of Morgan, New Jersey. Martial law is declared. People fear for their lives and safety. Survival is the question, and no one knows for certain.

Life gets a vote.

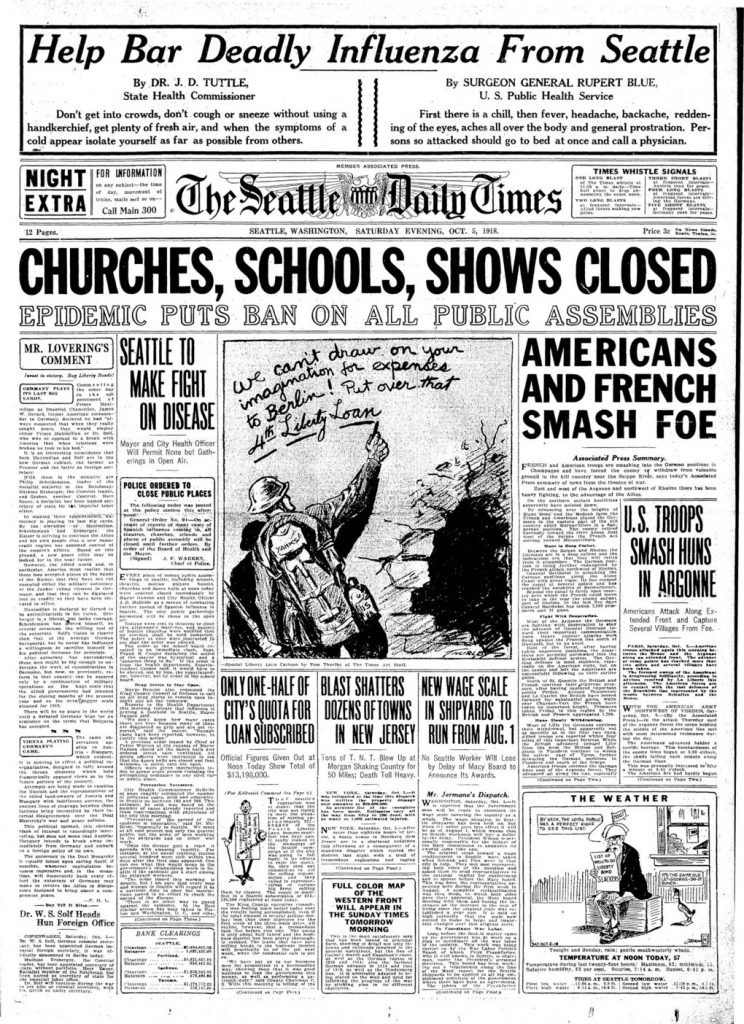

One of the largest non-nuclear explosions in American history rips apart the T.A. Gillespie Company Shell Loading Plant in this small town. The foundations of houses crack. Glass windows shatter. 94 people die with many more unaccounted for. Volunteers and bystanders carry the wounded and the burn victims to hospitals already strained by influenza. Fires burn and secondary blasts erupt. Rumors fill the air like the roar, smoke, and flames. Surely, many townspeople conclude, German secret agents detonated a bomb here at this massive producer of the American war effort. So goes the thinking—just look around at the sickness they injected into American life; why would this be any different? It’s their way of life fighting our way of life.

Police and military specialists sort out the details of what happened.

In Janesville, Wisconsin Dr. S.B. Buckmaster considers the way that influenza and the World War intersect. To him, an influential doctor of longstanding, the danger of intersection is clear—the World War is vital to the nation and influenza distracts or confuses an American public that must keep first things first. He believes that too many “false” reports of influenza are circulating. They hurt American morale and lower American morale helps the enemy.

Twenty miles east, people who live in Delavan, Wisconsin don’t care what Buckmaster thinks. Today they mourn the loss of a beloved community leader, Dr. Ray Rice. The 44-year old doctor was known to all in the town as a caring, dedicated physician. His death from influenza leaves a hole in the town’s fabric. People like him don’t just show up every day.

Further north, in Green Bay, Wisconsin, 17-year old Sylvia Van Veghel dies of influenza. We’ll never know what her future might have been in the place of her choice.

The response to influenza in the Midwest spans a spectrum. Health officers in Cleveland, Ohio decide today to begin reporting the sickness. In Nebraska, taking the Buckmaster view, the North Platte Board of Health insists that rumors of influenza locally are only that—rumors, nothing more, get on with living. In Indiana local boards of health in a village, town, or city have the final say on whether to close specific schools; some have done so. At the University of Cincinnati’s site for new soldiers, Don Wallace writes in his diary that after feeling slightly better, he is sick again. Wallace decides on his own not to report back to the hospital—and thus isn’t counted in the daily report—because two men there are dying of influenza. Since he’s still in his barracks, Wallace joins his comrades ordered today to scrub walls and floors with creolin, a natural disinfectant made from dry distillation of wood. At Camp Custer in Battle Creek, Michigan the camp surgeon reports no new deaths from influenza or pneumonia. Maybe a good sign?

Across all military camps, 331 deaths occur in the last twenty-four hours. Oddly, the reporting is from only a minority of camps. Some medical officials in the US military worry that the absence of reports suggests a worsening of conditions. The data is incomplete and unclear. In the fog, influenza wins every battle.

The fog acquires a strange thickness. On this day and every other day, many Americans on the outskirts of society—excluded by prejudice, bias, or sometimes choice—face additional danger and problems in influenza. Some Jewish residents of Pittsburgh, for example, do not speak English. They rely on others to share information from English-based newspapers. In addition, those newspapers written for Jewish-only readers tend to downplay the sickness and highlight the World War. And to make matters worse, the city’s more affluent Jewish residents frequently blame the illness on their poorer neighbors, emphasizing poverty, not biology, as fuel for the pandemic.

Day 27 brings hope, terror, despair, certainty, and doubt.

Life checks all the boxes on the ballot.

A thought for you on Day 27, April 8, 2020, twenty-seven days after President Trump declares Covid-19 a national emergency—the not-knowing. This day in 1918 underscores ten times in black marker the point of not knowing. For us in the Covid-19 crisis we’re told to do things and, more or less, we’re trying to do them. But inside, outside, above, beneath, without, and within everything is this: a universal reality of not knowing the details, not knowing whether yesterday’s fact is today’s fiction or the other way around, not knowing how deeply, pervasively, and stupefyingly other truths—like that for Jewish residents in Pittsburgh—work against people for outrageous and intolerable reasons. The not-knowing is tiring and numbing. It can work toward ruin and destruction. As a leader, you likely would trade practically anything so you could know even just a little more definitively about x or y or z. And, on top of that, whenever your followers ask you a question or seek an answer, you’re left saying for the umpteenth time: “well, I just don’t know.” You may hear yourself saying it so often that you drift into doubt and withdrawal. You’ll have to accept it for the foreseeable future, for the next month at least—not knowing is exactly what you will know most and know best. Look to build and maintain trust between you and your followers in other aspects of your relationship, in other parts of your conduct, action, and demeanor. If you make a mistake in your assertions of knowing, own up to it, and move on. Do the same with your followers. Not-knowing is not going anywhere. Pull up a chair or clean off a shelf, make room for not-knowing to stay a while. You can live with it.

(note to reader—I invite you to subscribe to this series/blog. The purpose of my posting in this series is the purpose of my enterprise at Historical Solutions—to explore the past in a new way that brings new and different value to you, both in the present (this minute) and on the edge of the future (what’s ahead or forward of this minute). The past is everything before now, the totality of all time before the present; history is a set of very small slices of the past that, for a particular reason, have been remembered. If you wish to contact me privately, please do not hesitate to text or call 317-407-3687)