October 2, 1918, the 25th day of influenza after its appearance at Fort Devens, Massachusetts.

There is a feeling that the worst is here and that the worst is headed somewhere.

Deaths and cases roll into new areas across the nation—in Camp Gordon, Atlanta, Georgia; Red Cloud, Nebraska; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; and the Naval Training Station at the University of Washington near Seattle. At Camp Meade, Maryland twin demons run loose—both pneumonia and influenza kill soldiers today. Boston, Philadelphia, New York City, and other metropolitan areas continue to report cases and deaths. Nurses are among the sick and dying in Chicago. Across scores of American military posts, the existing record of the highest number of new cases in a single day shatters after only a single day. Today sets a new high for uniformed soldiers and sailors.

Amy Hunter is a student at Vassar College. She now has influenza but can’t find room at the two medical facilities currently overflowing with patients. She stays in bed in her room. Many of her sick friends must do the same.

Frances Huffman, the talented new teacher at a small school in rural Indiana, a bright future in front of her, has influenza. Her fever hovers around 103 degrees. When she’s able to communicate during the day, she blames the Germans for spreading the illness. A friend writes a secret letter to Frances’s mother and expresses fear over Frances’s condition.

A speck of good glimmers in the day. People do get better: Don Wallace, the sick soldier at the University of Cincinnati, is feeling well enough to get out of bed and return to his barracks. He sits down for his first full meal in several days. Sitting down at a lab bench in New York City is Dr. William Park, chief bacteriologist with the municipal health department. Dr. Park begins work on a potential vaccine. Standing near him are some of his staff. They are the volunteers ready to test his findings. Hope fills Park’s lab.

Some of the glimmer seems to be gold. A respected doctor in Austin, Texas sits for a newspaper interview. He tells the townspeople that this October is absolutely nothing new, no cause for alarm—same old, same old as far as seasonal flu is concerned. The editor of the Austin Statesman is so convinced by the doctor’s remarks that a special headline appears: “Spanish Influenza Discussed In Intelligent Manner.” And in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania the local public health director is already busy ignoring calls to close taverns and restaurants. Even in the best of times the people of this city cough and hack from the black smoke of blast furnaces and steel mills. “Don’t worry, finish your beer” is the essence of official attitudes where two rivers make the Ohio.

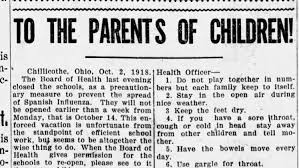

These communities are in direct opposition to others with a different outlook on this day. Several days ago town leaders in Greenfield, New Hampshire had closed theaters and schools. Now, though, they expand the closures to include the public library and all churches. An order blankets the town: no more meetings of any kind until further notice. Harsh action in the shadow of the White Mountains.

A thought for you on Day 25, April 6, 2020, twenty-five days after President Trump declares Covid-19 a national emergency—you live, and lead, where you are. In American life, the responses to influenza occur on the ground in the spaces where people have organized and chosen to live together. As those spaces grow in number and range, they also add layers of complexity and sources of friction. A leader who is place-based and ground-bound—as in Greenfield, New Hampshire, for instance—can take advantage of change that has a sense of horizontal movement: last week we did A, while this week we do A+B, and so on. A leader responsible for multiple places and widening expanses of ground—varieties of Greenfields, you might say—faces the broader challenge of maintaining a horizontal coherence more natural to a single Greenfield. The pressure to splinter builds and, sooner or later, demands an offering of greater countervailing power and control, at which point either acceptance or rejection occurs. This decision of acceptance or rejection will almost certainly come at a time of a still deeper crisis within an influenza-like event. The bonds of people where you live and lead will be sorely tested.

(note to reader—I invite you to subscribe to this series/blog. The purpose of my posting in this series is the purpose of my enterprise at Historical Solutions—to explore the past in a new way that brings new and different value to you, both in the present (this minute) and on the edge of the future (what’s ahead or forward of this minute). The past is everything before now, the totality of all time before the present; history is a set of very small slices of the past that, for a particular reason, have been remembered. If you wish to contact me privately, please do not hesitate to text or call 317-407-3687)