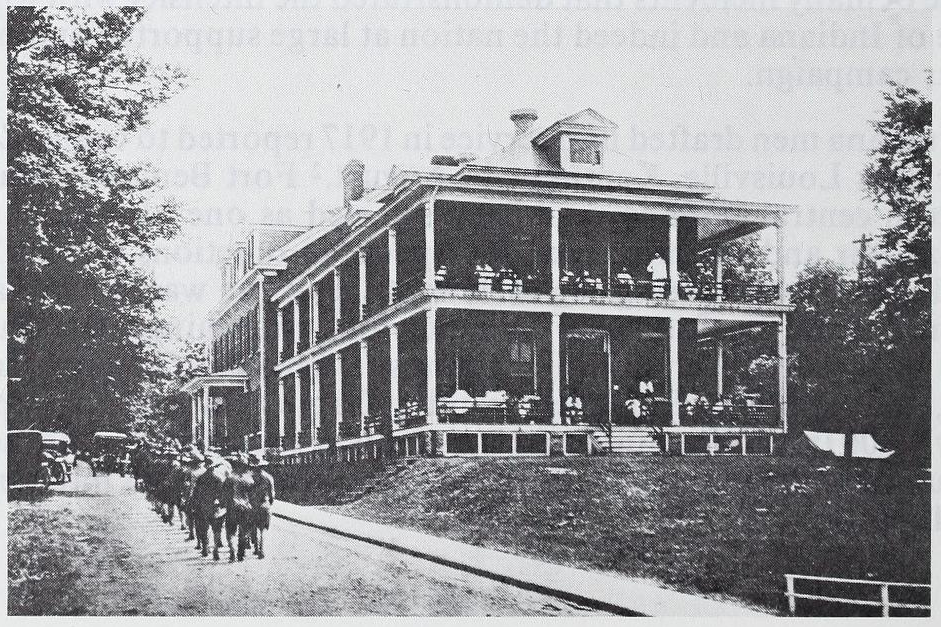

A young nurse leans over a sick soldier, wipes his forehead, and gives him a drink of water. She smiles and speaks softly. He opens his eyes, the color of his face is pale but not blue. Not yet, thank heaven. She moves away and leans over the next soldier on a cot, and the next, and the next. Twenty-five in all. This is Day 23, September 30, 1918 at Fort Benjamin Harrison near Indianapolis, Indiana. There are twenty nurses to care for 500 sick soldiers. So great is the need that a handful of soldiers are being trained in basic nursing as a way to ease the burden on these remarkable young women.

In Indianapolis itself the mayor has ordered a thorough scrubbing of street cars, hotel lobbies, railroad stations, and movie theaters. The hope is that influenza can be contained at the fort, in a local hotel, and in a school for hearing-impaired children, the places where influenza has broken out in Marion County, Indiana.

But today’s news is this: four cases of influenza are reported elsewhere in the city.

The cage is empty and the beast is out.

600 cases of influenza fill hospital quarters at the University of Washington Naval Training Station in Seattle, Washington. Isolation of hundreds of influenza patients begins in Minnesota. In Philadelphia the weather turns mild, giving hope to doctors who assumed that warmer temperatures would restrict the spread of sickness. The opposite proves true today—less than forty-eight hours after the Libery Loan parade and residents of Philadelphia stagger into doctors’ offices, hospitals, and any public space with beds and a modicum of nursing care. One of the afflicted in Philadelphia dies within hours: classical music vocalist Maude Sproule, a fixture in the city’s orchestra. In Brocton, Massachusetts the funerals have been averaging one per hour. The town’s postmaster writes to this wife and warns her to stay away from any funeral service. The decision to honor the dead is a decision to become the dead.

Life is becoming defined by cloth. At Yale University campus officials began to hand out muslin facemasks to the students. At the University of Cincinnati, Don Wallace was in his second day of suffering with influenza. Wallace watched from his bed as nurses and orderlies hung blankets from wires to separate the sick from everyone else in the medical facility. Is that what separates life and death now? Masks around your nose and mouth or blankets serving as walls?

A thought for you on Day 23, April 4, 2020, twenty-three days after President Trump declares Covid-19 a national emergency—the twenty nurses. In terms of solutions to problems and answers to questions, thre is nothing so far to be done. The young nurses aren’t really healing; no one can. They’re working hard to help the patients’ bodies heal themselves. And yet there’s no edge, no sense of an end in sight and certainly no sense that a cure or transformative treatment is coming. How do you keep going if you’re one of the twenty nurses or, for that matter, anyone involved in the influenza pandemic. How do you keep going? Let the nurses show us—you do what you’ve been trained to do, what you’ve become skilled at doing, and what you know and feel deep down in simply and always the right thing to do. And you do that over and over, again and again, repeat and repeat. In the doing and redoing is a purpose and a call from a voice only you can hear. The voice can guide. Let the voice live out in the eyes of your soldiers.

(note to reader—I’m a day late posting. Sorry for that. I invite you to subscribe to this series/blog. The purpose of my posting in this series is the purpose of my enterprise at Historical Solutions—to explore the past in a new way that brings new and different value to you, both in the present (this minute) and on the edge of the future (what’s ahead or forward of this minute). The past is everything before now, the totality of all time before the present; history is a set of very small slices of the past that, for a particular reason, have been remembered. If you wish to contact me privately, please do not hesitate to text or call 317-407-3687)