Do you know that thing you’re doing? That sacrifice and extra effort? Well, you better get yourself ready to do more.

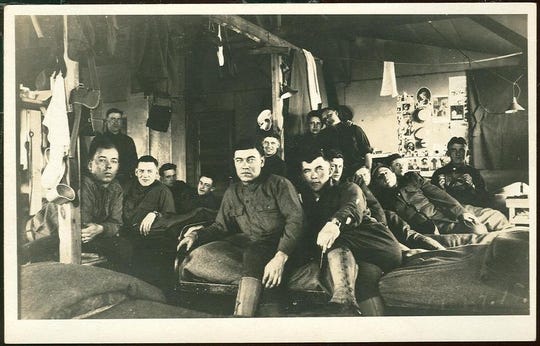

Today, Day 22, September 29, 1918, doing more than expected is how life goes. At Fort Devens, Massachusetts the medical facility was meant for 1200 patients. No longer—6000 sick men were there. At Camp Grant, Illinois a 10-bed capacity was blasted open in six days to allow for 4,102 influenza patients, with the largest single-day admission of newly sick soldiers, 788 cases, arriving since yesterday. No end in sight.

At Camp Grant doing more isn’t quite the same for everyone. The food portions for sick African-American soldiers look smaller than those given to other patients.

Don Wallace, a farmer-turned-soldier at the University of Cincinnati, can’t cope any longer on his own. He reports to the military doctor on campus, who gives him “several different kinds of pills” and sends him back to his quarters. Wallace’s buddies received a “second shot” and “when they got back they took us sick ones around (the) corner by ourselves and quarantined the whole quarters.”

A medical officer marks Wallace and his buddies as formally sick with influenza. Adding Wallace, the national toll for US military personnel is now 51,217 soldiers suffering from the illness. That total doesn’t include all those soldiers who haven’t reported sick but, like Wallace until today, have chosen to stay in their barracks.

Those who understand the situation are predicting pneumonia will also skyrocket any day now. At the same time, a report is out in the New York Times that researchers at the Army Medical School have developed a “serum” that will be used.

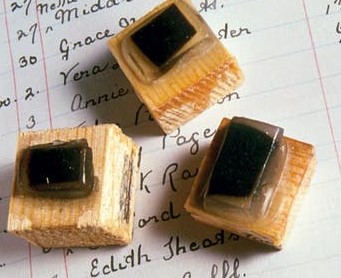

Stuck in wax, a lung of Private James Down sits in a container at an office in Charleston, South Carolina. It will be shipped to the Army Medical Museum on the National Mall in Washington DC. Down died a few days ago in Charleston.

US Army Surgeon General Charles Richard is not far from the National Mall. Had you asked him, he likely would have said he felt like he was stuck in wax, too. Richard has been sending memos, notes, and letters almost daily to US General Peyton March, the commander in charge of much of the American war effort in France. Richard has been cajoling, insisting, and repeating warnings to March about the deadly seriousness of influenza. To Richard, influenza is now an issue of national defense, at least as dangerous as the Germans and likely more so. March isn’t budging. To him, the enemy is certainly a three-letter word but it’s not f-l-u. March spells enemy “H-u-n.”

Speaking of the war, the Meuse-Argonne offensive rages on. An African-American unit from one of the richest cultural centers in New York City, the Harlem Hellcats, is part of horrendous fighting on the scarred landscape of northwestern France. General John Pershing, in France, writes that “we were no longer engaged in a maneuver for the pinching out of a salient, but were necessarily committed, generally speaking, to a direct frontal attack against strong, hostile positions fully manned by a determined enemy.” The Hellcats and thousands of other American soldiers can attest to that.

Doing-extra-and-then-doing more takes a different form in other places. In Boston, the cherished Irish tradition of holding a wake for the newly deceased is officially banned as of today. Influenza is killing people who gather to remember the dead.

A month ago the suggestion of such a change would have been laughed at. No more. Now people are wondering what next unimaginable change is twenty-four hours away.

A thought for you on Day 22, April 2, 2020, twenty-two days after President Trump declares Covid-19 a national emergency—I just never thought it would get this far, or I just never thought___would happen. Think of the people of Boston, of Irish ethnicity. It doesn’t take a lot to imagine the shock they experienced when learning that wakes were prohibited. A treasured custom at the most poignant and meaningful moment in the life of a loved one is now gone. Do it and you break a rule, a law, an ordinance, a makeshift community-wide life-and-death attempt to stem the worst public health crisis in anyone’s memory. What’s your first reaction to “I never thought it would…”? And after the first reaction, what comes next, your second reaction? At what point do you shift from gut-level reacting to some sort of considered thinking-and-doing? You need to know where your lines are from first to second and from second to third, and so on. I’ll suggest this with all respect and compassion—the less you descend into assigning blame and guilt, the more you’re able to get to the thinking-and-doing stage. Right now, as we’re grappling with “I never thought it would get this far”, it’s a good idea to be able to think-and-do as swiftly as possible.

(note to reader—I invite you to subscribe to this series/blog. The purpose of my posting in this series is the purpose of my enterprise at Historical Solutions—to explore the past in a new way that brings new and different value to you, both in the present (this minute) and on the edge of the future (what’s ahead or forward of this minute). The past is everything before now, the totality of all time before the present; history is a set of very small slices of the past that, for a particular reason, have been remembered. If you wish to contact me privately, please do not hesitate to text or call 317-407-3687)