News large and important. Printed in newspapers, transcribed on telegrams, written in letters. Read by thousands, read by dozens, read by one. Word is spreading about life in a world that is—like it or not, choose it or not, know it or not—abruptly new. Day 18, September 25, 1918.

For the thousands…

A leading newspaper in Charlotte, North Carolina, the Observer, reports that Spanish influenza is based on a germ. That’s the science for readers to understand. More than that, though, is the newspaper’s recommendation on what to do: “Only by loyal and intelligent co-operation of the general public can the epidemic of Spanish influenza be prevented from spreading throughout the country and hampering our war work. Do your bit.”

A leading newspaper in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the Inquirer, features an article wrapped around a hope—it’s hoped that Camp Meade, 118 miles away in Maryland, will not find it necessary to go into quarantine. The opinion in the newspaper lags behind life on the ground. The camp has been in quarantine for the past twenty-four hours.

A leading newspaper in Lewiston Maine, the Sun-Journal, includes a statement from local doctors in the town. They’re confident—downright and dead-dog confident—that the sickness is just a “hard cold.” Nothing else. Unspoken but clearly implied is their likely next statement: buck up.

For the dozens…

A telegram arrives in an office on the campus of Brown University. From the Health Education Committee (HEC) in Washington DC. The HEC was set up to monitor and improve the health of young men entering the American military for the World War; expectations were veneral disease would be the biggest concern. Today, however, a shift is visible in the wording: “Exercise great care as to the health of men Period They must be properly housed in sufficiently warm quarters Period (…) Permit men to wear their own warm clothing when in your judgment necessary.”

For the one…

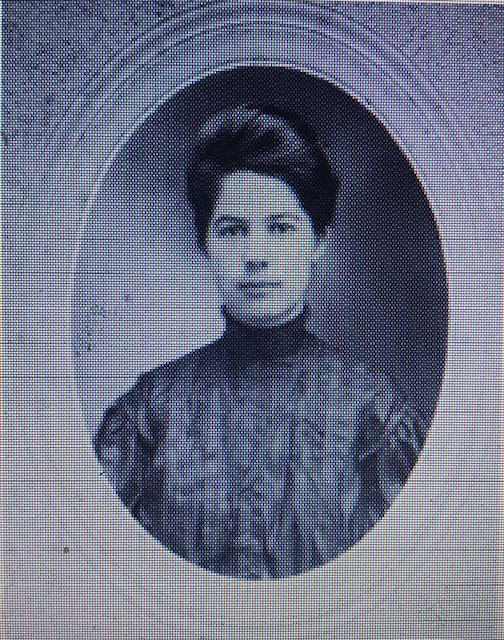

Frances Huffman writes a letter to her brother. Frances is 30 years old, a recent graduate of Indiana University, and in her first job as a teacher. She is excited about her career, devoted to her students, an asset in any and every school. She’s been busy with teaching her rural students—five classes a day with three assemblies—and dealing with their active social life of music, dances, and parties. She adds this in her letter written and mailed today: “Be sure you don’t get the Spanish flu. Several of our high school folks are out with it and several grade chaps. They sprinkled Lysol all over the floors of the school house except for the high school room, and we are all gargling Listerine here where we board. Am also taking cascara tablets. Am feeling fairly well just now.”

New York City Health Commissioner Royal Copeland writes a very short note to the city’s mayor, John Rylan. Copeland informs Rylan that he will look closely at a recent letter from Solomon Rosenbaum. One of the city’s business leaders and possessor of a nation-wide vision, Rosenbaum had offered suggestions on steps to prevent the spread of influenza. “It has had our attention,” Copeland writes, “and further reply will be made at an early date.”

Beyond the letters, telegrams, and newspapers are events that begin to change people’s lives on this day.

New soldiers board a train at Camp Lewis in Seattle, Washington. Their destination is Fort Stevens, Oregon, 190 miles away. The reason for the trip is to learn how to fire artillery in battle. The train pulls passenger cars packed with men. Inside the passenger cars, rumbling along the tracks, several soldiers are coughing, sweating, feeling achy. A few hours later, the train comes to its stop at Fort Stevens. Everyone disembarks. The sick men don’t fall in line for training duty at the artillery field. They head straight to the camp hospital. The train blows its whistle, signaling departure for the next load. The white smoke trails off in the air of the Pacific Ocean.

A few soldiers at Winnetka, Illinois are still grousing about the latest decision there, not far from Lake Michigan. They’ve been told that a favorite Saturday activity, the Jackie-band dances, have been canceled until further notice because of influenza.

A thought for you on Day 18, March 30, 2020, eighteen days after President Trump declares Covid-19 a national emergency—do your bit; and I’ll take a look and will get back to you. Let’s you and I put the last remark in the Observer article together with the brief note written by Copeland. Every person has a role to play. Every person can contribute, make an effort, and regardless of whether a clear outcome or result emerges, every person has a responsibility…and a duty (a word that is sadly out of fashion at the moment) to act. No one is too important and no one is too unimportant. And yet, one of the temptations will be to lapse into “business as usual.” That’s the feeling I get when I read Copeland’s notes to Rylan. “Yeah, we’ll get around to it…” You can just feel the bureaucraticness (new word?) in the letter. These two things are wildly incompatible—you can’t expect everyone to do their best-bit but while at the same time half-shrugging off the need to take the extra step, go the extra mile, and, God forbid, give serious consideration to an idea or two AND TAKE ACTION that may come from a new source. So ask yourself—is this what I do? Have I shown through my own behavior my commitment (here it comes!) to do my duty?

(note to reader—I invite you to subscribe to this series/blog. The purpose of my posting in this series is the purpose of my enterprise at Historical Solutions—to explore the past in a new way that brings new and different value to you, both in the present (this minute) and on the edge of the future (what’s ahead or forward of this minute). The past is everything before now, the totality of all time before the present; history is a set of very small slices of the past that, for a particular reason, have been remembered. If you wish to contact me privately, please do not hesitate to text or call 317-407-3687)