You turn the corner and there it is. A sudden shock. The look and feel of an unknown that is total, that is capable of swallowing up everything you are and everything you’re ready to do. Beyond your experience, your expectations. Beyond all there is in you. You turn the corner and there it is.

On this fifteenth day, September 22, 1918, a young mother and her two young sons wake up in Wilmington, Delaware. It’s the first day without her husband and without their father. He died some hours ago from influenza. They turn the corner and today is life without him and life with a mysterious sickness all around them.

A college student at Dartmouth College writes his mother. He admits that probably twenty or so students have some sort of strange illness that acts like the flu. “I only hope I can steer clear of it,” he writes, “at present I am okay.” He adds that a professor died last night; rumors fly across campus this morning on cause of death. They range from influenza to suicide. Everyone has a theory on the corner turned with this unexplained death.

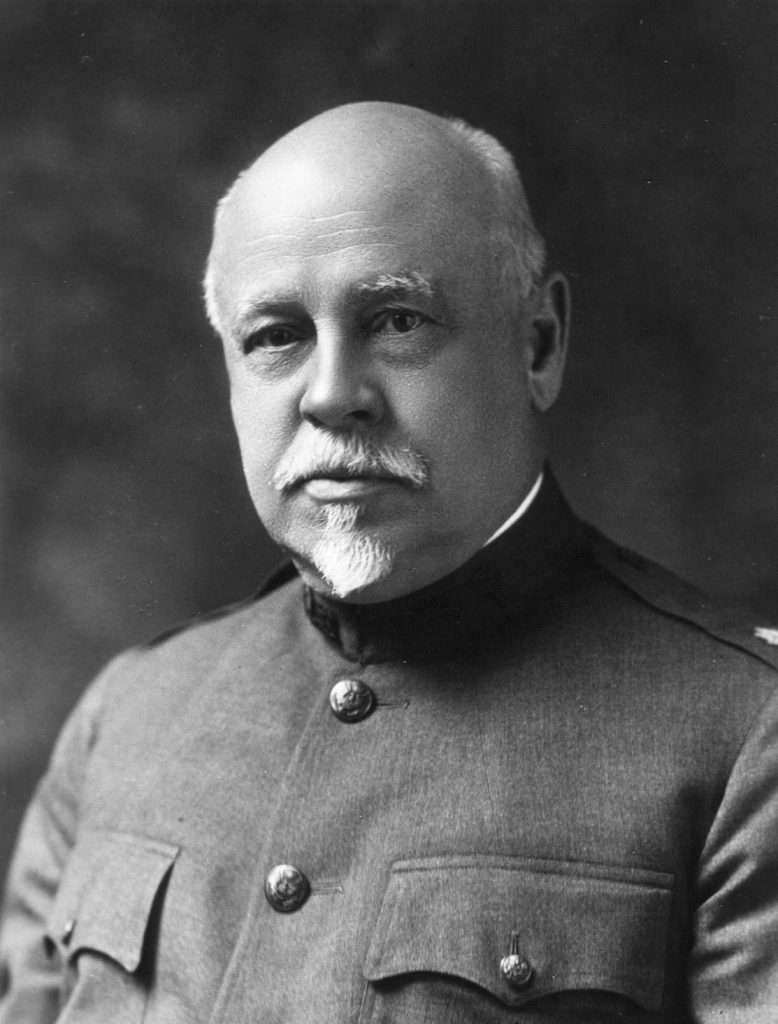

Dr. William Welch, a lieutenant colonel in the US Army and one of the most skilled medical professionals in the United States, arrives with three colleagues at influenza’s ground-zero, Fort Devens in Massachusetts. He’s following orders from the US Surgeon General to get to the military post as fast as he can. More than 10,000 of the fort’s 45,000 soldiers have influenza. Dr. Welch has vast experience, knowledge, and judgment. He’s seen everything.

In a cold rain, he turns the corner.

And what he sees changes him. Sick men are everywhere. Their faces are blue. Their coughs bring up drips and streams of red blood. Their hair is matted dark with sweat, eyes sunken and traced in nearly black circles. Their bodies limp and sapped of strength and energy. Minute by minute and hour by hour death slides closer. Welch and the trio of medical professionals with him are speechless. Words aren’t forming into thoughts, let alone ideas. They can’t now.

And then, rain falling from the gray sky, they enter the morgue. Around the corner.

On tables, the floor, countertops, anything flat, bodies are stacked like wood, like stone, like hulks of waste, like everything heavy that has no life. They wend their way through the piles and the heaps and the mounds, stepping over single bodies here and there and finding spaces to place their next footprint. These forms are waiting for something. To be made invisible.

Still another corner and around it Welch goes to where an autopsy is happening. He watches. Then, he sees more and sees nothing that his experience can understand—the chest is open and the lungs are there—blue, entirely blue, expanded in size, soaked and seeping in a foamy condition. Welch stares, gathers a quick breath, stares again. He knows what he doesn’t know and seeks for what it might mean. He forms a notion, rapidly: it could be an entirely new type of influenza. Or plague. That could explain it. But it’s bad, it’s awful, the implications can’t even be estimated, and we need to turn the corner, right now.

The day is nicer in Cleveland, Ohio where Dr. Harry Rockwood, the city’s Health Commissioner, warns residents Spanish flu is on the way here. It’s a regular thing, like we’ve had before, he tells them, so cover your coughs and sneezes and stay home if you’re sick. The readers of the New York Times see essentially the same advice in the day’s articles. There’s a corner but it’s the corner we always turn.

A thought for you on Day 15, March 27, 2020, fifteen days after President Trump declares Covid-19 a national emergency—those corners. There are thousands of them in the course of your life. Perhaps one will come today. You might sense the dimensions of it, you might not. Think of the Wilmington mother and her boys, Welch at Fort Devens. They had their corners on the same day. Certainly different in numerical scale but really no different at all in personal impact and personal consequence. Neither the mother nor Welch was truly and completely prepared for the nature of the turn and the reality waiting on the other side. The best they could do was to try to do their best. I think that their best came from somewhere—from something else outside themselves. It’s none of my business what your “something else” is. It’s my hope, however, that you’ll take the time and make the effort to explore your source of the something else. Turn the corner.

(note to reader—I invite you to subscribe to this series/blog. The purpose of my posting in this series is the purpose of my enterprise at Historical Solutions—to explore the past in a new way that brings new and different value to you, both in the present (this minute) and on the edge of the future (what’s ahead or forward of this minute). The past is everything before now, the totality of all time before the present; history is a set of very small slices of the past that, for a particular reason, have been remembered. If you wish to contact me privately, please do not hesitate to text or call 317-407-3687)