Two weeks on, September 21, 1918, and the remedies started flowing in. Some folks say don’t let your feet get wet and watch out for signs of blocked bowels. Others assert that chewing food well and drinking lots of water is the answer. Eating onions, drinking sour milk, the list grows of what people hope will be the cure, the trick, that keeps them healthy and alive.

Rolling in with the remedies were more new places with first cases—in Seattle, Washington at Camp Lewis; in Chester, Pennsylvania. First deaths, too—in Washington DC and Chicago, Illinois. Sometimes it’s not a case that is first but rather a flood of cases at the same time—seventy soldiers show up sick, nearly all at once, at Camp Grant in Illinois. Hartford, Connecticut is the scene today where the tally of cases has reached 500 in a few days’ time. This is testimony to the swift and encompassing power of influenza.

In New Orleans, the quarantined banana boat of the United Fruit Company rocks gently in the current of the Mississippi River. A doctor boards the vessel to test people confined there. The city waits on the knife’s edge—is it here or not?

The Philadelphia Department of Public Health and Charities decides to urge residents to avoid crowds and orders local doctors to report all cases of influenza. A reporter at a newspaper in a nearby town guesses that all of this sickness is the wartime enemy’s doing, “the underhand work of the despicable Hun.”

The people of Syracuse, New York hear a local doctor share his thoughts on this day. He is Dr. Dwight Murray of the city’s Crouse-Irving Hospital. A respected physician, Murray is active in his state’s professional medical association. Murray’s recent days have been filled helping patient after patient suffering from influenza. His hospital is packed with these cases and there is no end in sight. Perhaps worn down by the pressure, Dr. Murray talks sternly today with his community: “If we Syracusans are selfish enough to ask for a year-round (military) camp here, we will have to put up with this condition all the time during fall and winter.”

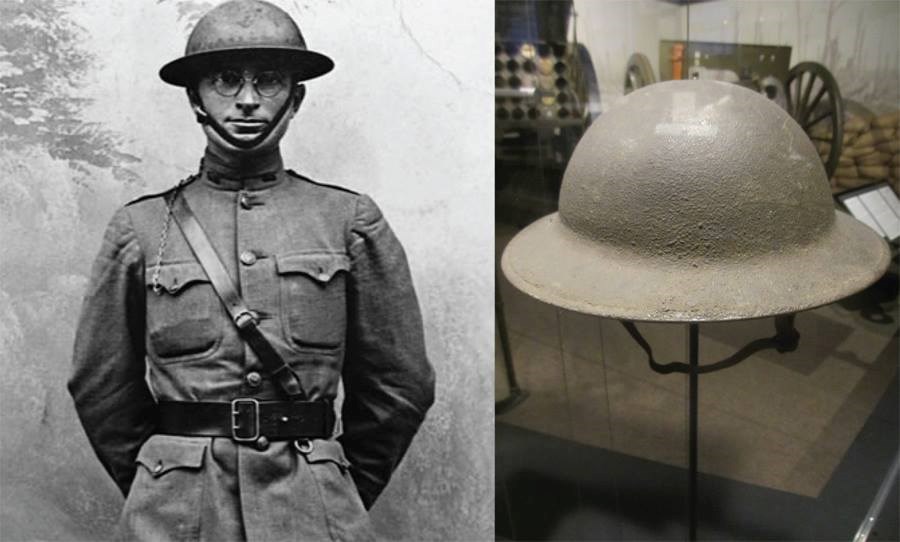

And on a muddy road in France, a group of men, one called “Captain Harry” by the others, continue struggling eastward—horse-drawn cannon and all—toward something that feels big, important, and violent. Captain Harry S. Truman wipes the sweat from his eyeglasses.

A thought for you on Day 14, March 26, 2020, fourteen days after President Trump declares Covid-19 a national emergency—the words of Dr. Murray. Hmmm. On one hand, he’s right. Yes, the city had happily joined in the mad scramble to get a military site located there. Lots of new federal dollars for the community, the chance of the town’s lifetime. And yes, he’s right again that this medical event, this unfolding tragedy, will largely be tied to natural forces like the changing of the seasons. But still—on the other hand. His patients who didn’t choose influenza. They didn’t seek out the world’s deadliest pandemic in the past 400 years. They didn’t predict—and nor did he—the onset of such a horrific event when their nation and their town went to war. Dr. Murray gives us a moment we need to remember. We have to do two things at the same time: see and know and acknowledge the facts while showing compassion and kindness. Understand, and be understanding.

(note to reader—I invite you to subscribe to this series/blog. The purpose of my posting in this series is the purpose of my enterprise at Historical Solutions—to explore the past in a new way that brings new and different value to you, both in the present (this minute) and on the edge of the future (what’s ahead or forward of this minute). The past is everything before now, the totality of all time before the present; history is a set of very small slices of the past that, for a particular reason, have been remembered. If you wish to contact me privately, please do not hesitate to text or call 317-407-3687)