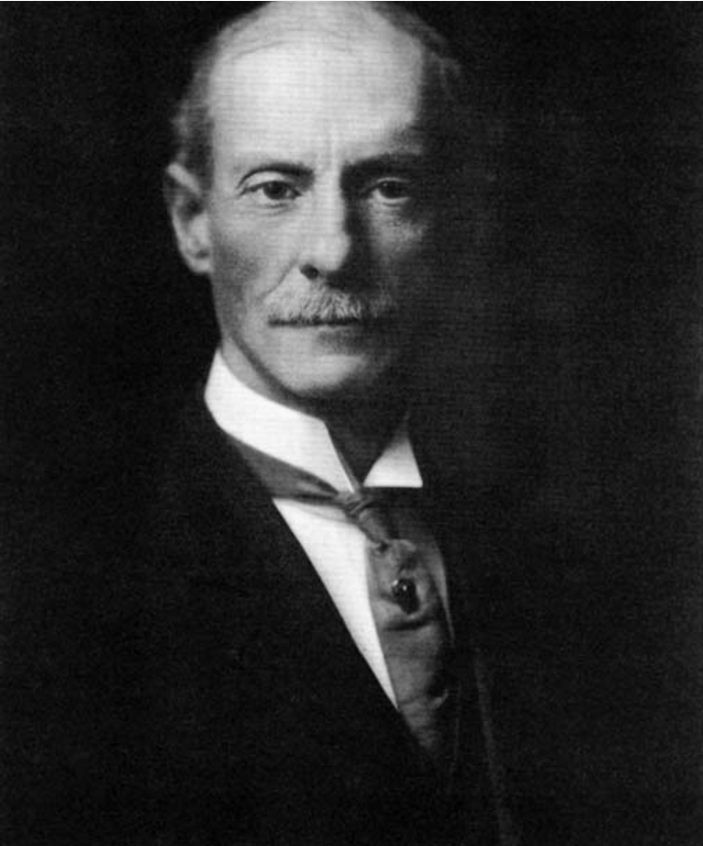

The phone rings at an office in the state capital of Indiana. The ringing is heard at the wooden desk of Indiana’s Secretary of the State Board of Health. Dr. John Hurty. Holding up the heavy black phone to his ear with one hand, Hurty hears US Surgeon General Rupert Blue on the other end of the line. Hurty listens for a few moments, asks a question or two, and then thanks Blue for the call. Hurty hangs up.

Hurty now has orders from Blue, his boss essentially, to begin gathering information on influenza in Indiana. Blue makes similar calls today to Hurty’s colleagues in the other 47 states of the US.

Today, very soon after hanging up, Hurty convenes a meeting with four of his staff. He gives them his own set of orders—you four inspectors, he says, go out to manufacturers in the city who are involved in making arms or war-related materials for our war against the Germans. And so, in the city laid out as a smaller version of Washington DC, out the door of Hurty’s office they go to find out who in their respective workforces is sick or getting sick.

In the hills of eastern Kentucky, in the town of Worcester, Massachusetts, and next to the Mississippi River in Memphis, Tennessee, people wince from severe coughing, their throats tighten uncomfortably, and fever starts to burn. They don’t know it but their next three days may be a descent into torture.

Back where it all seemed to begin with a handful of cases a dozen days ago, at Camp Devens in Massachusetts, nearly 10,000 soldiers are ill with influenza. 20% are in serious condition. Camp officials have suspended any passes for soldiers to leave the camp. They do allow those to depart if they promise that their home destination is within “walking distance.”

At another military facility, the Naval Training Camp in Charleston, South Carolina, a pair of realities co-exist, strangely and awkwardly. The camp is in quarantine with 350 sick sailors, while naval officers there say “the disease seems to be well under control.” Perhaps both can be true. Perhaps not. Doesn’t matter, though, because both do exist, one as a point of data and one as a point of outlook.

A thought for you on Day 12, March 24, 2020, twelve days after President Trump declares Covid-19 a national emergency—so much to say here, I’ll just pick one. Notice Hurty’s action after the call with Blue. He sends some of his followers out to gather insights in spaces related to the war. That’s the frame of reference or, if you will, the lens. It’s frustrating to know that Hurty and the four investigators are measuring their first step through this lens. But the hard truth is that we all have them. No one is free of the lens. I could tell you I’m free but that would be lying. And here’s still another tough aspect of it, the more unique and unusual and unprecedented something feels, the more critical it is to realize that the lens is there. It’s vital that you and I look for the lenses all around us, including ours. The best chance to begin to understand a) the situation and b) each other is to at least acknowledge the lens. If so, then the step after that has a much better chance of being worthwhile.

(note to reader—I invite you to subscribe to this series/blog. The purpose of my posting in this series is the purpose of my enterprise at Historical Solutions—to explore the past in a new way that brings new and different value to you, both in the present (this minute) and on the edge of the future (what’s ahead or forward of this minute). The past is everything before now, the totality of all time before the present; history is a set of very small slices of the past that, for a particular reason, have been remembered. If you wish to contact me privately, please do not hesitate to text or call 317-407-3687)