Far north. Far south. A young couple in love and a couple of perspectives on the day.

Let’s take them in turn and a few others in between.

Day 36, October 13, 1918.

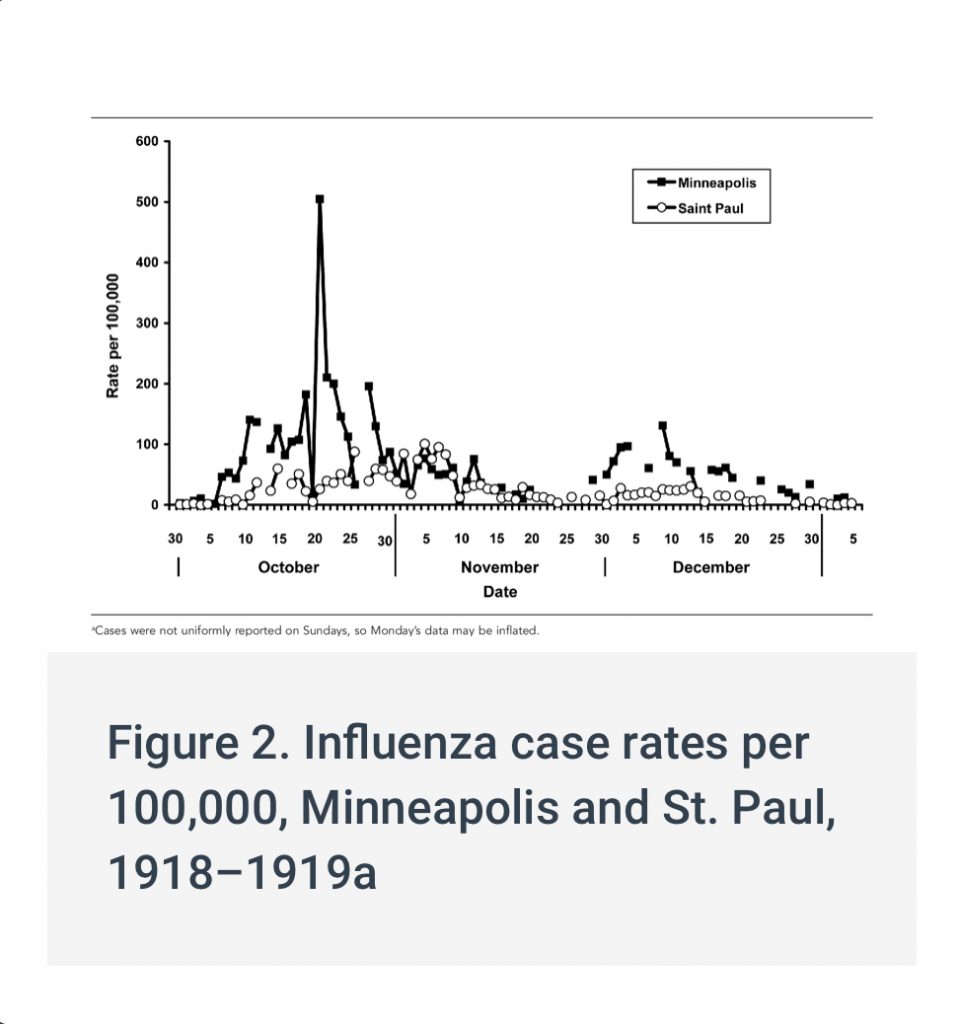

Minneapolis and St. Paul are side-by-side in Minnesota. Together, today, the two cities reel from the misery of influenza. It’s the first day that many places of public gathering, theaters among them, have been closed. The University of Minnesota has started efforts to find a vaccine. Early indications haven’t shown much. Soldiers in a nearby military camp are getting sick and dying every day. To many people living in Minneapolis and St. Paul, things feel like they’re getting worse.

And they’re right to feel that way. The data of the day is the proof. For them, though, the question is tomorrow. What will tomorrow bring? More of today? Better than today? Just another day like today?

Not knowing is an agony unto itself. You tend to fill in the blanks with your sense of now. Self-administered, that makes the agony go away. You assume, you know, you expect.

Other people in other places know this, too. In Buffalo, New York the strain of influenza is so great that there aren’t enough doctors in the community to keep up with the illness. One of the primary hospitals in Baltimore, Maryland refuses to accept any more patients for any reason—those with influenza take up every bed, every square foot of space. Syracuse, New York allows for no further use of street gaslights, movies, theator, or churches; they don’t want anyone downtown until influenza disappears. Telephone service shuts down in Upper Marlboro, Maryland because there are no healthy telephone operators. They’re all sick with influenza. In Huntsville, Alabama the entire medical and healthcare profession is down to a single pharmacist. Everyone else in the profession is either sick, dead, or gone off to the World War.

Believe it or not, firsts are still going on today. The first soldier from Cottonwood County, Minnesota dies; he’s in military camp in Iowa. The first soldier from Lorain, Ohio to die overseas from influenza is George Dibble. Influenza wipes away a young man who is “widely known” in his hometown. The first time in Chicago that the number of sick is so great that a way to tranport them has to be adopted; ambulances are under consideration. When the darkness descends, it’s all too easy to forget that other people are just starting to experience what’s already commonplace to you.

And in Montgomery, Alabama, the one-time capital of the breakaway secessionist government known as the Confederacy of the United States, a 21-year old man is a Second Lieutenant in the US Army. He’s falling in love with a vivacious local girl, all charm and good looks. He is serving for a short time at a military camp located in Montgomery. City officials lobbied hard to get the World War camp and all the federal dollars they knew would be poured into it. Ironically and also cruelly from the standpoint of the young girl’s family, the camp is named “Sheridan” after the vicious Union cavalry general who burned and plundered Confederate homes during the Civil War.

Influenza afflicts 2,367 men at Camp Sheridan today. But not our young 21-year old. Thankfully for him, for the time being, he is healthy. And so he and his young girl friend walk among the Confederate tombstones in a cemetery not far from her house.

He reaches for her. “Zelda,” he says in his soft voice. She doesn’t answer. Instead, she slips away among the stones.

F. Scott Fitzgerald sighs. Will she ever marry me, he wonders.

A thought for you on Day 36, April 17, 2020, thirty-six days after President Trump declares Covid-19 a national emergency—the horizontal after the vertical. You look at the two graphs for Minneapolis/St. Paul in 1918. What follows today? How does the next installment of the horizontal number show up in the next measure of the vertical time? In real life as it’s lived in the moment, you never know what’s beyond the right-hand wall of the graph. It’s the wall that we can’t penetrate. We can only live it. And what it measures is what we live. The same reality is true for Zelda and F. Scott. They don’t know how their lives will unfold after today, after the tissue-thin curtain that spans our mindfulness of the instant present. It’s a constant assumption to draw conclusions from the present, to chisel our trends into the near future. OK. I won’t stop you. I can’t stop you. And truth be told I do it as well. But you and I together have to develop the discipline to step back and compel ourselves to look not just ahead but to look ahead as if now hasn’t happened. Don’t build from now, on top of now, with materials and mechanisms that last no longer than now. And don’t do it in this time of all times, in 2020 Covid-19, when we know that today still has as many firsts as it ever did and tomorrow will, too. Go ask read F. Scott Fitzgerald’s amazing novel, The Great Gatsby, and when you get to the last line…think of me, think of you, think of this moment.

(note to reader—I invite you to subscribe to this series/blog. The purpose of my posting in this series is the purpose of my enterprise at Historical Solutions—to explore the past in a new way that brings new and different value to you, both in the present (this minute) and on the edge of the future (what’s ahead or forward of this minute). The past is everything before now, the totality of all time before the present; history is a set of very small slices of the past that, for a particular reason, have been remembered. If you wish to contact me privately, please do not hesitate to text or call 317-407-3687)