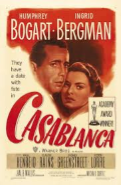

The war. The Second World War. And one of the greatest movies of all time. 80 Decembers ago it was almost ready for release. If you want a glimpse into attitudes that Americans of that time had for the world at large, here’s your chance to see it. Casablanca.

You likely know the story of the movie. Bogart plays an American, Rick, who owns a bar/cafe in Casablanca, Morocco. To his shock, Ilsa, a former lover, arrives at his bar—with her husband. All the pain of Rick’s break-up with Ilsa from a year ago is ripped open once again. Making matters worse is that Else and her husband are being pursued by German authorities. They desperately want a visa that allows them to leave Casablanca. Only Rick has the visa they need and the movie twists and turns toward the scene where he decides whether or not to help them leave Morocco and impending arrest by the Germans.

You likely know the story of the movie. Bogart plays an American, Rick, who owns a bar/cafe in Casablanca, Morocco. To his shock, Ilsa, a former lover, arrives at his bar—with her husband. All the pain of Rick’s break-up with Ilsa from a year ago is ripped open once again. Making matters worse is that Else and her husband are being pursued by German authorities. They desperately want a visa that allows them to leave Casablanca. Only Rick has the visa they need and the movie twists and turns toward the scene where he decides whether or not to help them leave Morocco and impending arrest by the Germans.

The war’s impact on the movie is obvious. It’s the early 1940s and Germany is on the march. German power has spread throughout Europe and crossed the Mediterranean Sea to North Africa. Again and again you see reminders in the film of the early stages of World War II—the relationship between local French officials and their new German masters; the panic of people seeking travel documents to escape the reach of the Germans; the references made to an emerging German empire.

But for the first time, I sat in wonder at a vibrant sub-plot—the story of American attitudes toward World War II. As a film, Casablanca reflects an American understanding of the war in 1941-1942, both as something to be avoided and something to be accepted. The six writers who worked on the script—ranging from the original unperformed play to the group used for the film version—produced a masterpiece of dialogue with historical value. They give us a glimpse into a world largely forgotten. To know American attitudes in the early days of World War II, watch and listen to Casablanca.

Skepticism marked American reactions to pre-Pearl Harbor World War II. Americans kept their distance from the war. They had approached war idealistically in World War I—the Great War—and didn’t want a repeat of that disappointment. Such a combination of hesitancy and involvement can be seen in Rick’s desire to stay out of the fracas while acknowledging his experience in fighting German-allied forces in Spain a few years before. He’ll fight in a worthy cause. He’s just not yet convinced this cause in Casablanca is worthy enough. At least, he’s not convinced yet.

Rick the American is also the center around which other characters and their nations orbit. French citizens who resist the Germans are in his cafe. So too is a Russian bartender, depicted as emotional, potentially unruly, yet helpful in some taken-as-a-whole way. A British husband and wife are there as well. They are appealing, solid, and somehow clueless to the fast-moving pace of the world around them. Each of them is significant but unmistakably, Rick holds the greatest power, the most sway.

And there you have it—three of the main American allies in World War II: Britain; the Soviet Union; and French government-in-exile.

Two more points about Rick the American. Rick notes that “all over America they’re sleeping tonight…” This is a reference to the refusal of the United States to enter World War II. Despite isolated incidents between American and German naval forces, despite the real possibility that Britain, France, or both could succumb to the Axis enemy and Hitler gain control of the European continent, the American people rejected the use of the US military on the ground in Europe. It required something of enormous magnitude to wake Americans.

In another scene a German military officer asks Rick how he would feel if he saw German forces marching into New York. The German’s question points to the most important debate of the day in pre-Pearl Harbor America: how far will the United States allow Hitler to go before joining in the war? And does Germany represent an actual threat to invade North America? Until some dramatic event changes the dynamic, these are the questions that Americans are asking themselves in 1940 and 1941 before Pearl Harbor.

In real life, the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor smashes American neutrality to pieces. President Franklin Roosevelt declared war within hours of the attack. Germany dictator, Japan’s ally, declared war on the United States and before the month of December 1941 was over, Americans were once again entered into a world war.

But Casablanca offers its own supplemental part of the entry story. There is no sharp event in the movie, no equivalent to a shocking jolt like Pearl Harbor. Instead, Rick and Else meet secretly where, in Rick’s words, “they found Paris again.” This line is overlooked as a reference to the war—in addition to showing his love of Else, Rick is also showing that American have reminded themselves of the bonds and feelings that link the Old World to the New, Europe to America. Now renewed and rejoined in mutual appreciation, they take up the fight against a common enemy.

You’d never guess it but Rick also embodies American military strategy. In a series of meetings and plans dubbed “Rainbow”, American military leaders had concluded by 1941 that if the United States formally entered the war, the nation would follow a European-focused strategy. The very real chances that a multi-theater, global war would occur could have taken the US into an Asian-focused strategy revolving around Japan. The attack on Pearl Harbor was an ironic expression of Japan’s role in events. But Rainbow 5 placed American emphasis on Europe—Germany—first and foremost. Rick’s entire orientation is toward Europe, particularly Germany. While Japan and Pearl Harbor woke Americans from their slumber, the United States as a nation followed where Rick pointed: to Europe first.

Lastly, as I watched Casablanca’s closing scene, with Rick the American volunteer and Louis the French official strolling together into the night, my mind turned to the fog and mist that engulfed them. These elements represented the future, the unknown path of time ahead. And so it was for American audiences seeing the film for the first time in 1942. This was a moment when Allied losses and setbacks were the only visible stories, uncertainty and despair over the final outcome the only known things. The brilliance of the movie, to me, was its honesty in holding a thread of optimism in a reality of chaos and danger.

How far we have moved from such an assumption. We seem to have lost our grasp of the thread.

Casablanca takes you back to the United States of 1942, to the hopes and fears of Americans in that dramatic era and generation. Enjoy it again or for the first time with an understanding in your mind that the film reveals much more than romance.

I wonder if a film of 2022 offers such a glimpse into us today.