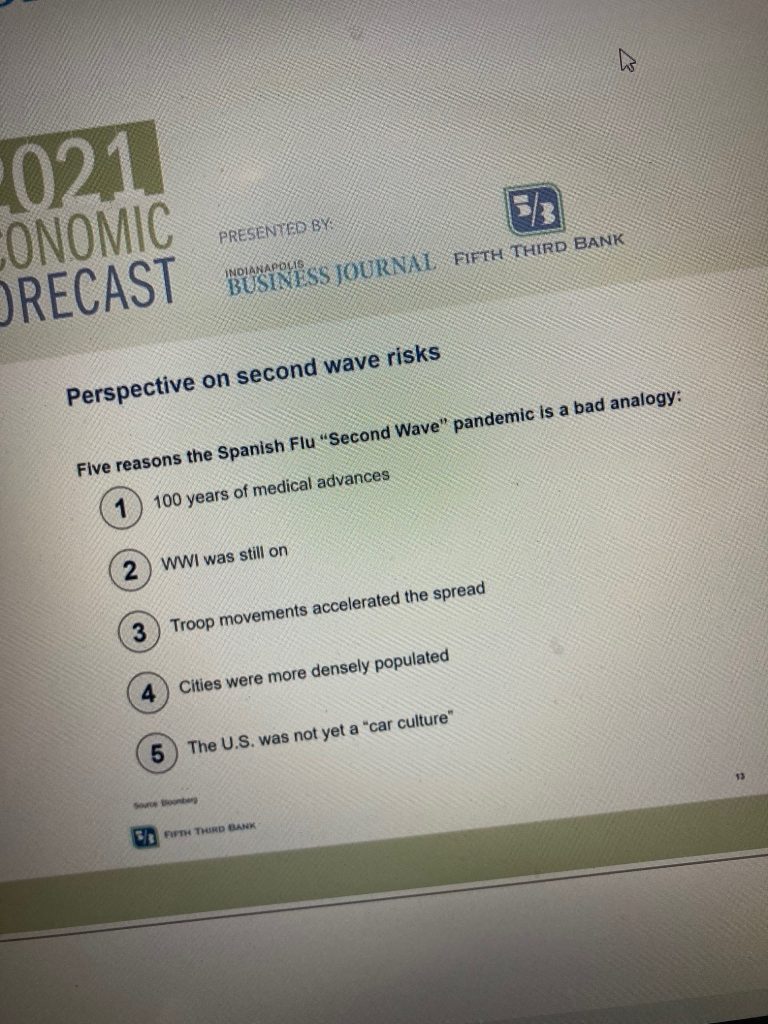

An alumnus of mine just sent me the screen shot of something dressed as analysis. It’s from a media outlet in my home state of Indiana. As a consulting leadership historian and, more importantly, someone who has real regard for the person who sent me the image, I offer a response.

As you’ll see, the five points that disqualify the analogy of the influenza pandemic’s “second wave” are as follows: 1) 100 years of medical advances; 2) the continuation of World War I; 3) troop movements spreading the virus; 4) cities more densely populated than today; and 5) US did not yet have a “car culture.” The five are wrapped in the paper of economic risk and business environment. The wrapping can’t hide the condition of the gift inside.

How about this…let’s do a fast take in turn. I’ve got hot coffee waiting on me.

First, no one in their right mind (an informal phrase meaning sanity, for IBJ staff) would ever ignore or reject the reality of the 100 years intervening. It’s triply true in the category of medical advances. This is a kindergarten version of the “straw-man” technique, whereby one presents an easily argument destroyed and thus its destruction serves to underscore and add credibility to the point being made. If you’re with the IBJ and reading this, I’ll wait as you re-read it. Also, there’s been a century of life in a trillion other aspects of reality and you’re obliged to weigh as many as possible in enriching the analogy being offered. I understand this because analogies are my stock-in-trade. A quick thought before moving on—America in 1918-1920 also had medical advances and in important instances had made significant improvements.

Second, those of you who know my concept of Warfluenza and Warcorona will know, or should know, that the key here is the collision of the dominant issue of the day with the public health crisis of the day. They interact. Influenza was not the total experience of Americans circa 1918. It was influenza along with the World War; they blended, they mutually affected, they combined, and above all, they confused onlookers, observers and, clearly, some people tapping out analysis on keyboards in 2020. Yes, the World War existed in Wave Two but so does our version of it in Warcorona—World War Trump. To not know the lessons of Warfluenza for Warcorona is to not know the importance of radio and railroad corporations for the digital economy. They’re there. The ignorance of them does nothing to prove their non-existence. It only proves the ignorance.

Third (my coffee is getting cold), troop movements had been spreading the virus since early 1918, to be more accurate. Yes, so what? Oh, and that’s also why it’s called Spanish Flu or the Three-Day Fever if you care to do any research on the matter. The war was critical to the virus. Separately yet connected, again, it’s all about Warfluenza and Warcorona and how the version of Wave Two’s share some important general trends, not least of which is starkly sharper levels of institutional difficulty, of civil trauma, and community pressures. We’ve been in Wave Two in 2020 before now because of Warcorona’s non-clinical problems in the K-16 education system. Only now are we seeing clinical statistics catch up to the weariness and tiredness already felt by anyone connected to students, teachers, and staff in the K-16 world.

Fourth, dense cities, less dense now (dense is a term I could use in a different context here). Got it. Then again, so what again? Take a look at the experiences in rural regions and isolated regions of the US in 1918-1920. It’s horrific. Doesn’t relate to urban density. The point isn’t densely populated cities in 1918-1920. It’s the combination of military encampments located in or near cities. That’s the key. And by the way, IbusinessJ, those encampments were economic development windfalls for every community that landed one; they begged for them to be chosen as such sites by the federal government. You might want to bear that in mind for the next quarter-century of 21st century economic development strategies. In other words, be careful what you wish for. Let’s repeat my one-last-thought—the more powerful point here isn’t density—it’s that isolation of populations was evident in even the most densely populated areas and it’s isolation that is the killing agent. Think about isolation in 2020. Anything come to mind? Moving on…

Fifth and finally (ice is now floating on top of my coffee), car culture and the lack thereof a century ago. Yep, it wasn’t there as you’re using the word “culture.” However, Americans circa 1918 had a car craze and you can see it plainly if you dig into what life was really like during the pandemic. For example, the governor of Massachusetts agonized over whether or not to keep the public shut-down in place during the worst parts of the influenza pandemic. He specifically commented that people had become used to—“dependent on”, IbJers—getting into their cars and going for pleasure drives on the weekends. He sensed that the inability to do that under the continued shutdown was having severe and serious mental health impacts on people in Massachusetts. I, for one, have great empathy for both the governor and residents of Massachusetts. We do them a disservice in not knowing their world.

Every analogy breaks down. Shocking! The far better, far more thoughtful, and far more useful point is to construct analogies that offer real worth. Such a thing is completely available in a proper and creative reconstruction of the 1918-1920 pandemic and it can be done for the emerging world of the post-pandemic. Stay tuned, I’ll be starting on a lot of that work in the very near future.

Thanks for reading and to my alumnus, thanks for sending. I’m off to brew a new cup of coffee. All the best, Dan