Next time you’re by a river, take a minute to stand and watch. Watch closely. The current has currents. Water is on top of water with different depths, bottoms, and barriers. The grade, the banks, the wind, each affects the shape and leaves a mark. There’s a lot going on in every river.

So, take a minute. Stand. Watch. Closely.

There’s a lot going on in the River of Day 55, the 1st of November, 1918.

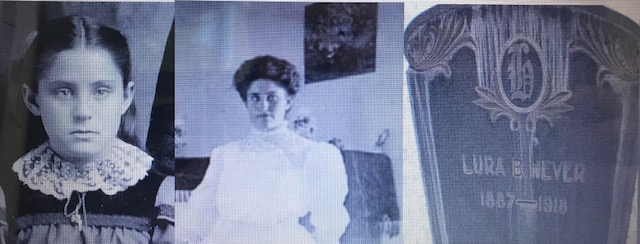

Life flows in Eagle County, Colorado for the Heyer family. Two young children are with their father. They’ve been keeping watch over Lura Bell McGlochlin Heyer, wife and mother, age 31 years. Everyone in Gypsum knows her, respects her, expects her for what she always is—kind, caring, concerned, involved. Nine days sick. Dawn of the tenth day now. Everyone waits and hopes and prays for her and the other twenty-four cases of influenza in the small mountain town.

In Gunnison County, still in Colorado, Dr. J. W. Rockefeller is in his first day with new power and authority. For reasons not entirely clear, the people of Gunnison have been especially aggressive in responding to influenza. Bans, closures, prohibitions, you name it, they’ve done it. Just yesterday the townsfolk decide that no one will be allowed to travel into the county. If you do, you’ll be seized and put into sequestration and quarantine for two days—essentially, forty-eight hours of individual isolation like the worst prison inmate, after which you’ll be free to enter and travel about Gunnison. Dr. Rockefeller is the guy with the new power and authority to make it real and make it work. Beginning today.

Forty-eight is a newly popular number in many American communities today. That’s the starting point—two days from now—when towns and cities that have shut down because of influenza’s flood will be opening back up because of influenza’s receding. The first tip of normal life is forty-eight hours away from today in Redstone, California; Knoxville, Tennessee; and Asbury, New Jersey, to name just a few. Like everywhere else, people are still getting sick and dying but in noticeably fewer numbers. So, forty-eight hours from now, they’re re-opening churches, schools, stores, and public places in two days. Weddings and funerals can happen again. You’ll be able to get a beer or a blessing, all in public with other people.

This kind of betwixt-and-between moment is also seen in the cartoons printed in newspapers. One of the most popular is “Mutt and Jeff.” Today, readers of the cartoon around the United States see the two main characters—one of whom has influenza—share in a little dark humor. They joke about the presence of sickness and the prospect of recovery. The sick character throws a shoe at the healthy character. You read the cartoon and know they’ll both be up to their normal antics again soon. It’ll be OK.

Cartoon humor can’t loosen influenza’s hold on American public life. Isaac Silverman, director of the Office of Motion Pictures in the War Department in Washington DC, learns that recently filmed “Fit To Fight” movies won’t be shown to anyone so long as theaters remain closed. The reels of these morale-building productions will stay on the shelf until further notice. The Stars and Stripes magazine for the American armed forces states the “epidemic is on the wane.” Shockingly, however, the same magazine compares the appearance of soldiers still wearing protective flu masks to white-sheeted Ku Klux Klan members; it’s unclear if the comparison is in approval or disapproval. No one knows how the upcoming election will fare—voters in Oakland, California will only be allowed to vote if they are wearing masks, while voters in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania may encounter confusion and obstructions from first-time poll workers rendered necessary by the impact of influenza. The power of influenza extends far longer than the re-openings two days away.

19-year old James Sheerin is a college junior in central Montana. He’s finished an article for his school newspaper, The Prospector. By sundown, today’s edition is available on the campus of Mount St. Charles. Sheerin thrills at forming his thoughts into ideas, his ideas into writing, and his writing into readership.

Perhaps more than he knows, the teenager’s insights will belong to a time. It is time in two forms, one that flows ahead and the other that never moves. The immovable one is the world he captures and records. It falls away, to the bottom, coming to rest as the flowing time moves further ahead, never stopping. The immovable piece of time holds secrets of the moment. Waiting in the water, it is a fossil among stones.

Sheerin forms his writing around a theme, the war. He adopts terms and phrases of the World War to describe the unhuman war waged by influenza. He writes of generals and soldiers and battles in the invisible war of the sickness. Sheerin also tells of separateness and uniqueness in the national life. At first, this unhuman war raged at a distance, on the East Coast and away from his beloved Rocky Mountains. Then, it came west and tore into this region of peaks, valleys, rivers, and plains. With heroic effort, though, the student-soldiers of his campus succeeded in fending off danger down to the level of the street. They had prepared for one war but fought another war. Across all the endeavor, marking all the experience, Sheerin thanks God and God’s heaven for victory over influenza.

It was war and place and spirit. And it was a blend of sorrow and hope, a noble suffering.

Day 55, and dusk becomes night and night ends the day. In the minutes before midnight, Lura Heyer begins to slip away. Her husband and children sleep near the banks of Eagle River. More water ahead.

A thought for you on Day 55, May 6, 2020, fifty-five days after President Trump declares Covid-19 a national emergency—the waters of the River. It could be said of any day in my Today In 1918 series, but this day in particular the truth seems especially clear—there are so many different things swirling in time as we experience Covid-19, just as was true for 1918’s influenza. We could stop on any one item and use it to extrapolate a wider theme. Here on Day 55 we see shifts toward a decline in the sickness and a rise in re-opening; we see continued suffering; we see the intermingling of public issues and a pandemic; we see a doctor given great power for a short-term future and a college student looking reflectively at recent experiences; and so on. I think what strikes me is two-fold. First, notice the tone of Sheerin’s writing. It is amazingly confident, grateful, and positive. How would you describe the tones you sense or observe around you now? Second, and more broadly, because of all the variations and subsets of experiences, it is all the more vital for you as a leader to set your mind to rising above them, to acting as either a unifying or at least a connective force. It won’t happen on its own. Left alone, the separate stays separate. But with the actions of leaders, great or small, far-reaching or within arm’s length, you can help add to the joining elements, the pivots and hinges. Get up and above and then reach over and across. Help the door stay attached to the wall, let it turn and open and close if it must. Don’t make your personal mission into the deadbolt or the lock and thrown-key. The connective leader is the leader now needed.

(note to reader—I invite you to subscribe to this series/blog. The purpose of my posting in this series is the purpose of my enterprise at Historical Solutions—to explore the past in a new way that brings new and different value to you, both in the present (this minute) and on the edge of the future (what’s ahead or forward of this minute). The past is everything before now, the totality of all time before the present; history is a set of very small slices of the past that, for a particular reason, have been remembered. If you wish to contact me privately, please do not hesitate to text or call 317-407-3687)