A hand held a pen. Ink on the tip. A few dashing strokes crossed out a word here, inserted a word there. The writer stared at the sheet, then stopped for the day. Almost ready as a book, almost finished as a story, almost born as a warning that, sadly, will never need to die.

“I’ll believe in you, if you’ll believe in me. Is that a bargain?”

In 1871 so said the Unicorn, written by Lewis Carroll, who is really Charles Dodgson.

Through the Looking Glass.

On Day 40, October 17, 1918, fingers hover barely an inch above the keyboard of a typewriter. Waiting inside, packed in rows, are metallic bits at the end of metallic arms. Soon, the pressing and the pounding begin. Letters fire against the spooled ribbon. A clean sheet, coiled around a cylinder, absorbs the blows. Words pile in heaps on the white field. Imagined on a tiny scale, where dust is a hill, the scene is like a battle with nothing alive. Something else commands the moment and the wider war.

The combat of a six-page letter is waged today.

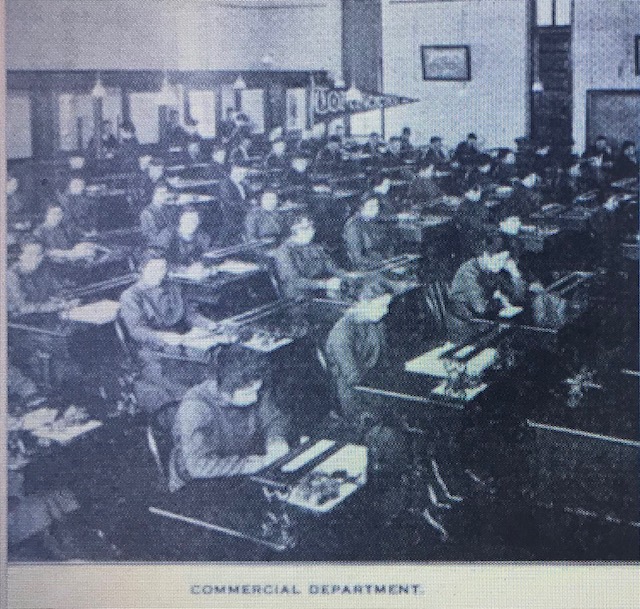

A Native American girl, one year out of the Haskell Boarding School in Lawrence, Kansas, is in Washington DC working in the office of the Interior Department. She is, variously, Lutiant Van Wert or Luciant La Voye, not quite 20 years old. While at Haskell with her Native American classmates, she developed a skill in typing. She learned, among other things, to strike keystrokes in rhythm to music, her fingers moving like soldiers to the beating drums. She has volunteered for nursing at Camp Humphreys south of Washington DC. By now, she is back in the nation’s capital, back at her desk, back at her typewriter.

On Day 40, she types a letter to a friend at the Haskell School, in the county where later medical researchers will assert influenza first began in 1918.

The letter is as bloody a landscape as the Argonne woods.

The first words she types are that she hopes two of Haskell’s administrators will become ill and die from influenza.

From there, she recounts that her recent volunteer nursing stint at Camp Humphreys involved 12-hour work days; duties that ranged from taking temperatures to rubbing backs to making egg-nog and “a whole string of other things I can’t begin to name”; and watching orderlies haul out two corpses every three hours. As they near death, soldiers often call hopelessly for their wives, their loved ones. The first officer who died under her care left her numb and “I had to go to the nurses’ quarters and cry it out.”

She adds that the call has gone out for more nurse volunteers in Washington DC. She is on the list of respondents. So great is the need, she remarks, that just about anyone can become a temporary nurse. She also hopes that a recent bill in the US Senate will be enacted; it would allow for war workers to be released from their jobs while the pandemic rages. Time off work would be wonderful.

Her letter contains social and city observances, too. She states that the soldiers prefer “Indian girls” over “white girls” because the former were “not so easy.” She qualifies her judgment: “I guess maybe that’s their reason.” She comments on how beautiful the city is and that she and a friend are waiting to ride to the top of the Washington monument in an elevator. It’s closed for influenza.

But the letter has one other section.

The final portion of her descriptions of Camp Humphreys includes this scene: “Two German spies, posing as doctors, were caught giving these influenza germs to the soldiers and they were shot last Saturday at sunrise. It is such a horrible thing, it is hard to believe, and yet such things happen almost every day in Washington.”

In a shocking letter this is the most shocking statement. And, as it soon emerges, not a word of this statement is true. Moreover, it will trigger a national investigation.

Less than a week later, 31-year old Amelia McFadyen of Waynesville, North Carolina—corresponding secretary of the Waynesville chapter of the Navy League, a pro-war national advocacy group—will write an article for the local newspaper, the Carolina Mountaineer & Waynesville Courier. McFadyen will report that a powerful rumor had been spreading from north to south. Starting first in Fort Devens, Massachusetts and making its way south from camp to camp, post to post, the facts purported that Germans spies trained as doctors and nurses had been sneaking into tents and quarters and exposing American soldiers to influenza. Each time they were caught, each time they were executed, including an account of a nurse yelling before the firing squad fired that she would die once but she had murdered more than three hundred.

The Surgeon General’s office, Army intelligence, and the Department of Justice will launch an intensive investigation “to learn the identity of persons guilty of disseminating these stories, and it is stated that swift and condign punishment will be meted out to the guilty ones as soon as they are apprehended.” The purpose of the disinformation is the “weakening (of) confidence in the Army Medical Corps and the Red Cross nursing corps to destroy military and civilian morale.”

The opening segment of the joint federal investigation will reveal that the account appeared in Washington DC seven days before McFadyen’s article appears in the North Carolina newspaper.

Hold up the looking glass, subtract seven days from the date when McFadyen’s article ran—and you arrive at Day 40, October 17, 1918.

Say hello to the Unicorn.

A thought for you on Day 40, April 21, 2020, forty days after President Trump declares Covid-19 a national emergency—the looking glass. The life of a young Native American girl at a boarding school in the early 20th century was harsh, to say the least. She encounters realities I will know zero about; I can read them, learn them, remember them, but will never live them. She does. Her experience of influenza—and don’t forget the other way I’ve suggested you label it, warfluenza—filters through her other experiences before influenza existed. And don’t forget that it’s not simply a layering of experiences; it is a blending of them, too. A result of the interaction is often an acceptance of one thing as another thing. In her case, shown in the section of the letter about the firing squad, this acceptance is of the false as the true. The blending of experiences is always happening in your life as it was in hers. We must find the moment and the insight to step away, even for a moment, from the ceaseless blending. I step away and realize that I am wrong. You step away and realize that you are wrong. She needed to step away and realize that she was wrong. A major challenge of our Covid-19 event is that the pace of experiences—and I urge you to define broadly this term of experience—is so great and so encompassing that we ignore the blending in order to save time, save energy, save the effort it takes to see and know the blending for what it is. Staying where we are is just plain easier. Please, use the looking glass not to enter an alien world but to examine more carefully the existing world around you.

(note to reader—I invite you to subscribe to this series/blog. The purpose of my posting in this series is the purpose of my enterprise at Historical Solutions—to explore the past in a new way that brings new and different value to you, both in the present (this minute) and on the edge of the future (what’s ahead or forward of this minute). The past is everything before now, the totality of all time before the present; history is a set of very small slices of the past that, for a particular reason, have been remembered. If you wish to contact me privately, please do not hesitate to text or call 317-407-3687)